KINIGUIDE The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague, Netherlands, delivered its verdict on the South China Sea dispute between the Philippines and China last week.

Although the tribunal concerned itself only with the overlapping claims of the two countries, the proceedings were also closely watched by the neighbouring countries, including Malaysia, which has observer status in the tribunal.

The tribunal’s unanimous verdict marked the first time the South China Sea dispute was taken to an international court, and its findings could have implications beyond the overlapping claims of China and the Philippines.

In this instalment of KiniGuide, we dive into the murky waters of the South China Sea dispute and see what’s at stake, especially from Malaysia’s perspective.

How is maritime territory determined?

Maritime territory is determined through rules stipulated in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), which came into effect in 1994. Unclos has now been ratified by 168 countries, including by China and all the Asean countries, except for Cambodia.

It follows a much older legal principle known as ‘la terre domine la mer’, meaning that sovereignty over maritime territories is determined by who has control of the adjacent landmass.

Unclos recognises several types of maritime territories. Broadly speaking, the low-water line of a coast is taken as a baseline for measurements.

Among others, coastal nations are entitled to claim territorial waters of up to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometres) seaward, as measured from the said baseline. Countries are allowed to exercise full sovereignty over these waters, but must allow ‘innocent passage’ of foreign vessels, including military vessels.

Coastal nations are also entitled to the exclusive use of the natural resources found within 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) of the baseline. This is known as the exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Unclos also recognises continental shelfs under the sea, and allows economic rights similar to an EEZ to the adjacent country. This area may extend beyond the EEZ.

Crucially, Unclos stipulates that geographical features that are under the sea during high tide are not entitled to either territorial waters or an EEZ around them.

If a feature is above the high-water mark, but cannot sustain human habitation on its own in its natural condition, then it is considered a ‘rock’. These would have territorial waters around them, but do not give rise to claims of an EEZ.

What is the PCA?

The PCA is an inter-governmental body set up to settle disputes among states, state agencies, intergovernmental bodies, and the private sector (such as investors, in the case of investor-state disputes).

In that capacity, it is one of several options available under Unclos for dispute resolution.

It should not be confused with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) nor the International Criminal Court (ICC), which are also based in The Hague. The ICJ is a UN agency, whereas the ICC is a separate body that prosecutes crimes against humanity.

For the purposes of the arbitrating the dispute, it formed a tribunal in accordance to Annex VII of Unclos.

What is the South China Sea dispute?

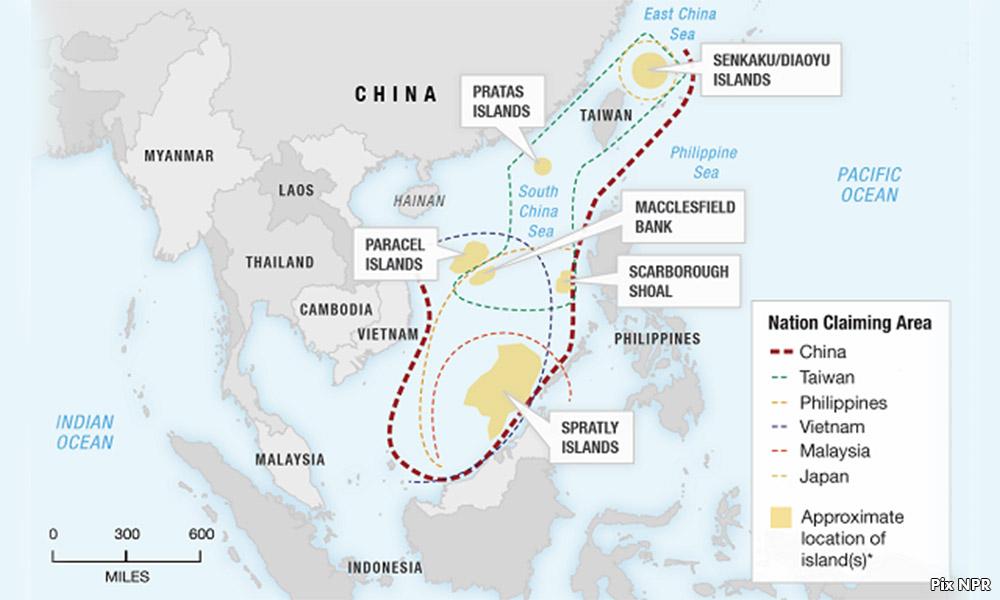

Several countries have made overlapping claims on patches of the South China Sea, and tensions over these disputes have sometimes led to standoffs at sea and even deadly naval skirmishes.

At stake is access to about 10 percent of the world’s commercial fish stock and about 11 billion barrels in oil reserves, according to figures reported by Bloomberg.

About 40 percent of China’s oil imports also pass through these waters, as well as imports from Chinese-controlled mineral concessions in several African countries. Some US$5 trillion (RM20.58 trillion) in trade passes through the area each year.

The disputes in the South China Sea are mainly among Asean countries, concerning who owns the islands in the sea (and by extension, the surrounding waters) and the limits of their respective EEZs.

For example, Malaysia and the Philippines have competing claims over the Spratly Islands, comprising hundreds of islands and reefs located to the north-east of Sabah.

Malaysia had laid claim to the features in the southern portion of the Spratly Islands and has military outposts on five of them, but the Philippines disputes some of these claims, as does Brunei.

However, China and Taiwan also claim sovereignty over many islands in the South China Sea, including the Spratly Islands, as well as ‘historic rights’ over large swathes of the South China Sea, popularly known as the ‘nine-dash line’ area.

The basis of this claim is a 1947/1948 map (there are conflicting accounts on this date), drawn up by China’s Department of Ministry of Interior, when China was under republican rule.

It has a broken line made up of 11 dashed lines demarcating large portions of the sea as Chinese territory, although some of the later maps marked roughly the same area with nine dashed lines instead. These claims overlap with some of Malaysia’s current claims, as well as that of many other countries.

After Chinese republicans fled to Taiwan amid the communist uprising of 1949, both China and Taiwan continued to pursue these claims. China asserts that the 1940s maps are not new claims, but a confirmation of existing historical entitlements.

The tribunal observed that the nature of China’s maritime claims is never clearly stated, but said that in practice, China appeared to assert exclusive control over the natural resources in the ‘nine-dash line’ area, while allowing freedom of overflight and freedom of navigation.

Over the years, China has increasingly becoming more assertive of its claims in the South China Sea, including by conducting naval patrols and reclaiming some of the disputed islands as its own military outposts.

Last year, a Chinese coast guard vessel was found to have been anchored in the Malaysian-claimed waters near Luconia Shoals (also known as Betting Patinggi Ali), and reportedly refused to budge despite protests from Wisma Putra.

According to Reuters, there was also an incident where a Chinese coast guard vessel had charged against a Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency patrol boat, before veering off while blaring its horn. There have also been reported incursions by hundreds of Chinese fishermen in the waters claimed by Malaysia.

A series of interactive maps depicting the competing claims and related issues are available from the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, here.

How did the arbitration come about?

The Philippines initiated proceedings against China on Jan 22, 2013. Despite protests from China, leave was granted for the tribunal to proceed the following year.

Among others, the Philippines sought the tribunal’s declarations on whether China has any claim to the waters within the nine-dash line beyond those that China is entitled to under Unclos, and whether the features within the overlapping claims of China and the Philippines are capable of general maritime claims (such as territorial waters, EEZ, etc).

Of note is the fact that the Philippines did not ask the tribunal to determine who has sovereignty over the disputed islands. The tribunal has no jurisdiction over territorial land disputes.

China disputed the tribunal’s jurisdiction. Among others, it argued that since the tribunal has no jurisdiction over land sovereignty, it is in no position to determine maritime sovereignty of the surrounding waters.

China boycotted all of the tribunal proceedings, and issued a position paper in December 2014, arguing why the tribunal should not hear the case.

China boycotted all of the tribunal proceedings, and issued a position paper in December 2014, arguing why the tribunal should not hear the case.

The procedures of Unclos in such a situation dictates that the tribunal needs to satisfy itself that it does in fact have jurisdiction to decide on the Philippines’ claims. In addition, it needs to test the veracity of these claims by itself, even though China was not present throughout the proceedings to refute them.

To do so, the tribunal held a series of hearings on its own jurisdiction. It eventually ruled, on some of the issues, in favour of the Philippines on Oct 29, 2015, while deferring its decision on other issues.

It also appointed independent experts to report on some technical matters, asked the Philippines for more information to back its claims, and retrieved some hydrographic data and other data from UK and French archives and the public domain to compare.

All materials were provided to the parties, including China, for comment, although China never responded.

The tribunal was presided by five arbitrators led by judge Thomas A Mensah from Ghana. The others on the panel are Rüdiger Wolfrum (Germany) Stanislaw Pawlak (Poland), Jean-Pierre Cot (France) and Alfred HA Soons (the Netherlands).

What is Malaysia’s involvement in the arbitration?

Malaysia is an observer to the proceedings, with a six-member delegation. The other observers are delegations from Japan, Australia, Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand and Brunei.

According to the tribunal, Malaysia had sent two notes verbales (a less-formal form of diplomatic communication) dated June 23 urging that the panel ‘show due regard’ for Malaysia’s claims in the South China Sea, while emphasising that it is not seeking to intervene in the proceedings.

The notes reportedly state that some of the features that the Philippines asked the tribunal to identify, which are claimed by the Philippines, may also be claimed by Malaysia as part of its continental shelf limit in a 1979 map.

The tribunal affirmed that Malaysia’s interests do not form the subject matter of the dispute, and hence are not implicated by the tribunal’s conclusions.

It says that Malaysia has correctly observed that, since it is not a party to the dispute, “Malaysia is not bound by the outcome of the arbitral proceedings or any pronouncement on fact or law to be rendered by the arbitral tribunal”. This is in accordance with Article 296(2) of Unclos.

What is the verdict?

There are two salient points in the tribunal's verdict. The first is that China has no right to maritime entitlements beyond those allowed by Unclos, including China’s so-called ‘historic rights’ in the nine-dash line area.

It appears to concur with the argument by the Philippines that whatever historic rights China claims to have in the South China Sea were forfeited when China ratified Unclos in 1996.

The tribunal also held that while Chinese sailors had historically used the waters and islands in the area now disputed between China and the Philippines, there is no evidence that China exercised exclusive control over the waters.

In other words, the historical presence of Chinese and other sailors merely constitute the exercise of freedom on the high seas.

The tribunal also observed that during the conferences that led to Unclos, the issue of giving recognition for historic fisheries was considered, but ultimately rejected.

However, note that the tribunal could not, and did not, make a decision on who owns the disputed islands because it lacks the power to do so. This is where the second point comes in.

Within the Spratly Islands, the largest above-water feature is the Itu Aba, which is about 1.4 kilometres in length, 400 metres in its widest breadth and about 0.43 square kilometres in area. It is currently occupied by Taiwanese forces, which had set up a lighthouse, port facilities, a runway, and several buildings there.

Within the Spratly Islands, the largest above-water feature is the Itu Aba, which is about 1.4 kilometres in length, 400 metres in its widest breadth and about 0.43 square kilometres in area. It is currently occupied by Taiwanese forces, which had set up a lighthouse, port facilities, a runway, and several buildings there.

The tribunal ruled that Itu Aba, along with several other major high-tide features in the Spratly Islands, are incapable of sustaining human habitation by itself in its natural condition.

Under Unclos, it is considered a ‘rock’. Its soil is too poor to sustain agriculture and its freshwater sources are too fragile. The tribunal also found no evidence of these features having sustained continuous human habitation in the past.

This means that whoever owns such features are also legally entitled to territorial seas in the surrounding 12 nautical miles. However, these features would not generate a 200-nautical mile EEZ for its owner.

By implication, other features that are smaller than Itu Aba are even less likely to be habitable, and are hence correspondingly less likely to be found capable of generating maritime claims for whoever owns these features - if any claim at all.

As the tribunal put it, “The introduction of the EEZ (through Unclos) was not intended to grant extensive maritime entitlements to small features whose historical contribution to human settlement is as slight as that. Nor was the EEZ intended to encourage states to establish artificial populations in the hope of making expansive claims, precisely what has now occurred in the South China Sea.

“On the contrary, Article 121(3) was intended to prevent such developments and to forestall a provocative and counter-productive effort to manufacture entitlements.”

Suddenly, being able to lay legal claim to the land territories in Spratly Islands becomes a lot less valuable, even though such disputes are far from any final resolution.

You may find copies of the tribunal’s verdicts, expert reports, transcripts, and other materials by clicking this link.

What now?

The tribunal's decision is final and legally binding on China and the Philippines, but it lacks the power to enforce its rulings.

For such a sweeping victory, the mood in the Philippines government was markedly sombre, with its foreign secretary calling for ‘restraint and sobriety’. Statements from its ally, the United States, struck a similar tone.

Meanwhile, China warned of escalating tensions in the South China Sea and reiterated its position that it would ignore the PCA’s ruling. It has reportedly conducted combat air patrols over the area and intends to make this a regular feature.

Taiwan has also rejected the ruling, and claims that Itu Aba is legally the only island in the Spratly Islands (meaning it is also entitled to all natural resources within 200 nautical miles, if its claim of sovereignty over Itu Aba holds up).

Asean was reportedly unable to reach a consensus on what to say about the verdict, and ended up not issuing any statement at all.

Malaysia called for a peaceful resolution to the dispute through diplomatic channels. In particular, it urged for the implementation of the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and for an early conclusion of the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC).

The 2002 declaration is an undertaking between Asean and China to some principles in handling the dispute, such as to use peaceful means in accordance with international law, and to engage in cooperative activities, such as undertaking marine research, pending the resolution of the dispute.

The COC is envisioned as a more formal set of rules based on the DOC, but it has never materialised.

Malaysia is not bound by any findings of the tribunal. However, if it were to be involved in a similar arbitration with China, chances are that the new tribunal would independently reach similar findings, unless new facts emerge or if there is found to be an error in last week’s verdict.

This instalment of KiniGuide is compiled by Koh Jun Lin.