COMMENT | Malaysians are frustrated with stagnant wages. The government’s move on minimum wage was eagerly anticipated – and ultimately a disappointment for workers.

But policy debates and popular pressures should not stop at the legal wage floor. This historical juncture also presents an opportunity to enhance how Malaysia labours and lives, and to consider reforms not just to wages but also on work hours.

Effective January 2019, the monthly wage floor will move up to RM1,050 nationwide, from RM1,000 in the peninsula – a paltry RM50 increase. Lowest wage workers in Sabah and Sarawak enjoy a bigger gain of RM130, from the current RM920.

Technically, this is not a broken pledge. Buku Harapan promised to raise minimum wage to RM1,500 within five years – without specifying a schedule for incremental increases. Assuredly, the rate will be revisited.

By law it must be reviewed every two years, though on the heels of this unsatisfactory raise, I’m sure voices of discontent will amplify next year. It is good to maintain that pressure, for the sake of workers and their livelihoods, but also for the productivity and welfare improvements that minimum wage is supposed to propel.

Minimum wage is a potentially useful policy instrument, due to its extensive reach. The National Employment Returns Report 2016, a nationwide survey of companies conducted by the government’s Institute of Labour Market Information and Analysis (ILMIA), found that 60 percent of companies employ workers at minimum wage.

The survey also asked firms how they responded to minimum wage. In the cost and profit equation, 61 percent reported that compliance lowered profit, and 18 percent said they cut back on benefits to workers (allowances and bonus payments).

On the employment and output fronts, 37 percent reduced their workforce, while 17 percent deemed minimum wage a positive contributor to “productivity”, and 18 percent held the same for “competitiveness”.

On the whole, evidence suggests that negative outcomes associated with minimum wage have been considerably mitigated. Indeed, at its introduction in 2013-2014, the most disruptive point, the dire spectre of widespread unemployment, as painted by policy opponents, did not transpire.

It seems widely agreed that minimum wage continues to be imperative to remedy persistently low wages. But there are other fundamental problems with Malaysia’s labour market, besides a sluggishly rising monthly rate.

At root, we work a lot without necessarily making a lot while putting in the hours. Hourly wages are exceedingly low, weekly work hours are exceedingly long. Of course, monthly take-home pay matters and we are accustomed to budgeting on a monthly basis.

However, we stand to gain by stressing more on hourly wages, and striving for a more dynamic balance of high wages per hour and lesser hours. Concurrently, the national concern for productivity should also primarily emphasise output per hour worked, not simply output per worker.

Economy constrained by overworked labour

Malaysia’s economy is constrained by a perpetual dependence on overworked labour, especially migrant workers, who worked long hours and are paid low, hourly rates. This hinders technological upgrade and perpetuates work conditions that are unattractive to Malaysian workers, and detracts from the work-life balance that has been a national priority for many years.

Khazanah Research Institute (KRI), in its recent report Time to Think about Time, importantly highlights this problem of persistently long work hours in Malaysia, which robs time from relationships, leisure, rest and other meaningful and enjoyable pursuits.

How much do workers in Malaysia work? As KRI points out, the load has only slightly changed over the past decade, and averaged 45.5 in 2017, according to the Department of Statistics’ Labour Force Survey. This authoritative data source also reports a median of 48, meaning that half of the workers in Malaysia work 48 hours or more.

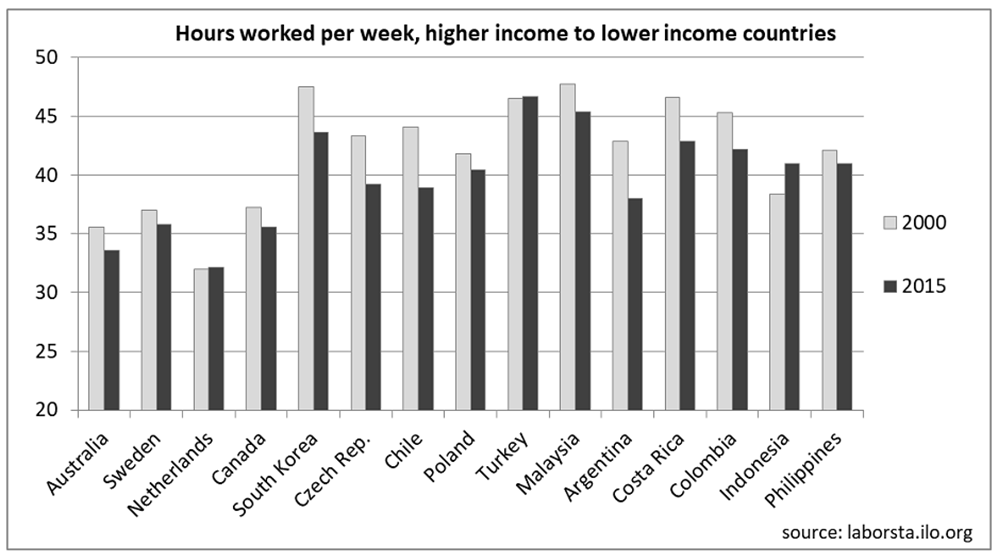

How does Malaysia compare against other countries? Let’s take a sample of various income levels, including a few Asian countries and Southeast Asian neighbours.

Like most countries, Malaysia sees a declining trend, but our level remains relatively high. We log more work hours than high income countries – as expected – but also tend to exceed upper-medium income peers like Argentina, Costa Rica and Colombia, and even lower-middle income countries like Indonesia and the Philippines.

Legislated full-time hours broadly correspond with national income level. Malaysia’s Employment Act (1955) stipulates a 48-hour work week. Among the sample in this chart, lower-income and middle-income countries are more likely to work similarly long hours. Full-time employment is also 48 hours in the Philippines, Colombia, and Costa Rica.

However, countries close to Malaysia’s income level tend to put the benchmark at 44-45 hours (Turkey, Chile, Argentina), while high-income countries – Poland, Czech Republic, Canada, Sweden, South Korea – have widely adopted the 40-hour convention: which recently also cut the legal maximum hours from 68 to 52 per week. Indonesia stands out among lower-middle income countries for setting the bar at 40. At the other end, in some high-income countries, the threshold is even lower at 38 in Australia, and 30 in Canada.

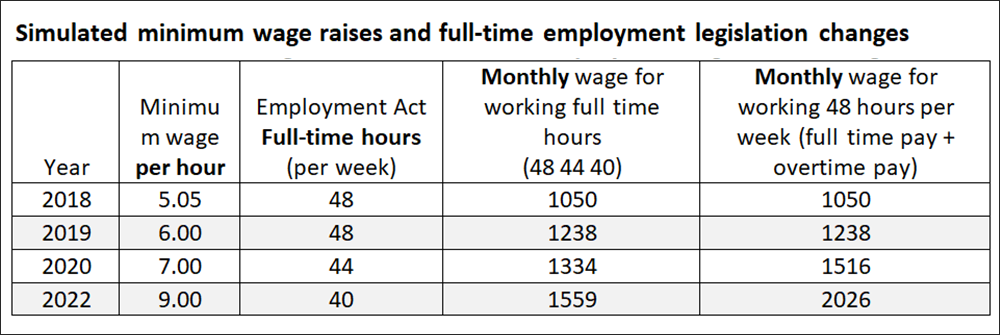

What does all this have to do with minimum wage, work conditions and productivity? Malaysia’s hourly minimum wage derives from the monthly amount converted to a weekly rate, then divided by 48 hours per week. The hourly rate effective January 2019 is RM5.05.

For many workers, transport costs and a meal probably swallow up two to three hours of wages, hardly a palatable offer. For employers and the economy as a whole, the cheap hourly rate continually inclines the labour market to generate low-skilled, low-productivity, labour-intensive operations.

From a long-term strategic standpoint, Malaysia introduced minimum wage to spur labour productivity and capital intensity, but this tool is blunted by the continual ease of imposing long hours at low hourly wages. Pressing harder on minimum wage per hour, while also reducing hours worked, enhances the capacity of minimum wage to propel the policy priorities in which we keep falling short.

Consider this simulation, a schedule of hourly minimum wage raises in tandem with Employment Act amendments lowering full-time hours. I should add that this simple example excludes urban-rural differentials, which should seriously be considered.

Reducing the full-time work definition from 48 to 44 and then 40 increases the “penalty” of imposing long hours, since overtime pay (1.5 times the hourly rate) will kick in beyond these thresholds. By this simple exercise, in 2022, the monthly wage will be RM1,559 for full-time work (40 hours), and RM2,026 for persisting at the current norm of 48 hours (40 hours on regular pay + eight hours overtime).

This is no panacea for our many labour market woes, but it is a potentially impactful instrument, for it applies greater pressure to raise productivity per hour, through technological upgrade, innovation and workplace improvements. High hourly wages also facilitate more gainful part-time employment, particularly in services where such improved options can be beneficial for society.

This firmly signals policy priorities and helps steer the labour market in a socio-economically productive and wholesome direction, while providing some room for adjustment. Employers can continue demanding 48 hour weeks of their workers – but must pay a steeper price for it.

Will employers cut back workers’ hours? Some will do so, and the terms should strive to maintain growth in workers’ take-home pay even if work hours decline. Or especially, if work hours decline, since this is a driving objective.

The 48-hour work week is no sacred rule. Why not break it?

LEE HWOK AUN is a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS).