MALAYSIANSKINI | Jerome Manjat is a hard man to reach. Appointments are rescheduled many times and it takes several phone calls before our scheduled video call comes through.

“I am sorry for all that rescheduling, my paper-making class dragged on and I have had to attend many meetings since coming back to Sabah,” he apologises, looking boyish in his yellow T-shirt and clean-shaven face.

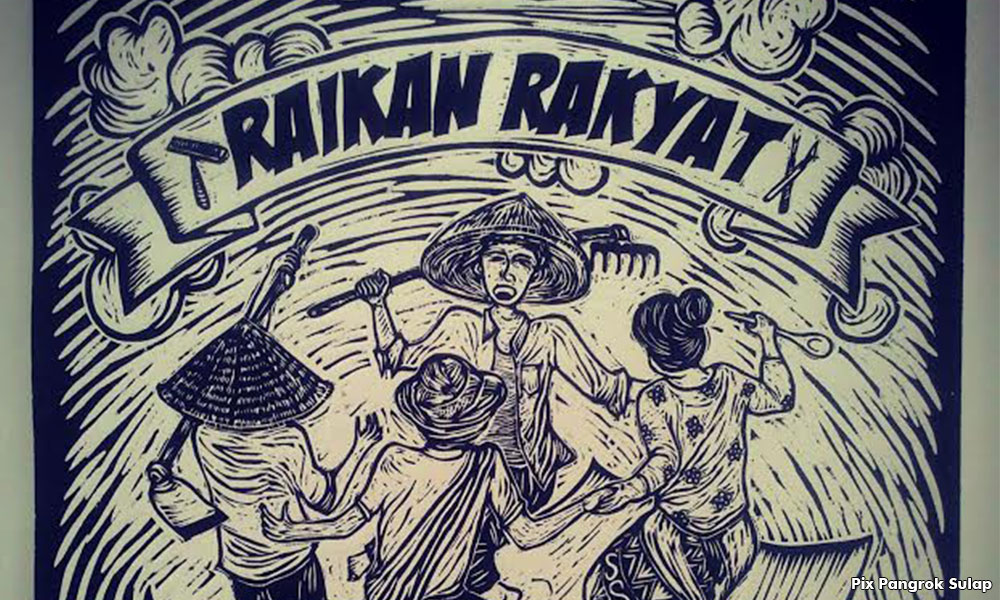

The words ‘Raikan Rakyat’ (celebrate the people) are seen on his T-shirt. Jerome and his friends made it at a public T-shirt printing workshop they ran two months ago.

Behind him are four people eating noodles on a wooden table draped with a brown and blue batik tablecloth. Colourful artworks give the fresh white walls a cheerful, childlike character. A painted poster of a clenched fist and the words “Mana hak kami” (Where are our rights?) stands out.

This is the living room of Tamparuli Living Arts Centre, where Jerome is the manager.

Jerome took over managing the centre last November and has since added artist residences, art galleries, a research library and a community garden to it. The late British artist Tina Rimmer left the four-acre property to be used for the arts but it had laid vacant for 20 years before it was slowly developed into an arts centre.

“This centre is not just for art but for preserving and promoting the culture of the Sabahan people. It is a place for the Tamparuli community to develop their knowledge,” he explains in English interjected with Malay phrases peppered with an instantly recognisable Sabahan accent.

The community garden, for example, grows various species of indigenous plants for the community to use for cooking and craft.

Jerome is a full-time manager, but it’s a volunteer position.

“At first I wanted to turn down the offer because I was so busy. But after I understood Tina’s vision I decided I really wanted to help make this happen,” he tells me.

Ban caused uproar

A fixture in the Sabah art scene, Jerome came under national limelight when two woodcuts, Pangrok’s signature art style, were removed from an exhibition in Kuala Lumpur last month.

“The organisers received complaints and were told they had been reported to the Prime Minister’s Office,” he explains.

The incident caused uproar among the local arts community, raising concern over censorship in Malaysia.

Jerome, who has been “drawing ever since he could use a pencil”, first drew up the plan for the woodcuts on a piece of paper.

“However the woodcutting process was quite spontaneous, the end product did not look like the plan at all. When we looked at the pieces we could not believe we actually carved it,” he says.

Both pieces, towering in size at 8 by 12 feet and rich in detail, are as imposing as they are inviting. Like royal tapestries, the pieces feature layers after layers of characters, buildings, plants, landscapes and stories.

Both pieces, towering in size at 8 by 12 feet and rich in detail, are as imposing as they are inviting. Like royal tapestries, the pieces feature layers after layers of characters, buildings, plants, landscapes and stories.

The first piece begins with a striking image of Mount Kinabalu at the very top followed by familiar motifs associated with Sabah. There are slogans like ‘Sabah negeri merdeka’ (Sabah is an independent state) and verses from the Sabah state anthem ‘Sabah tanah airku’ (Sabah my homeland). Tunku Abdul Rahman appears to be reading from a scroll into a microphone.

The piece depicts the stereotypes and misconceptions people have about Sabah, Jerome says.

With the second piece, the collective wanted to depict the real and often unreported issues faced by the Sabahan people.

It has people cutting, with scissors, into the state of Sabah. Right at the centre is a moustachioed-man with his hand stretched towards the viewer, in his palm are money notes with the words “belanjawan” (budget) on them. There is a man pumping petrol into another man’s teacup.

The former was exhibited at Balai Seni Visual Negara while the second was hung at APW in Bangsar.

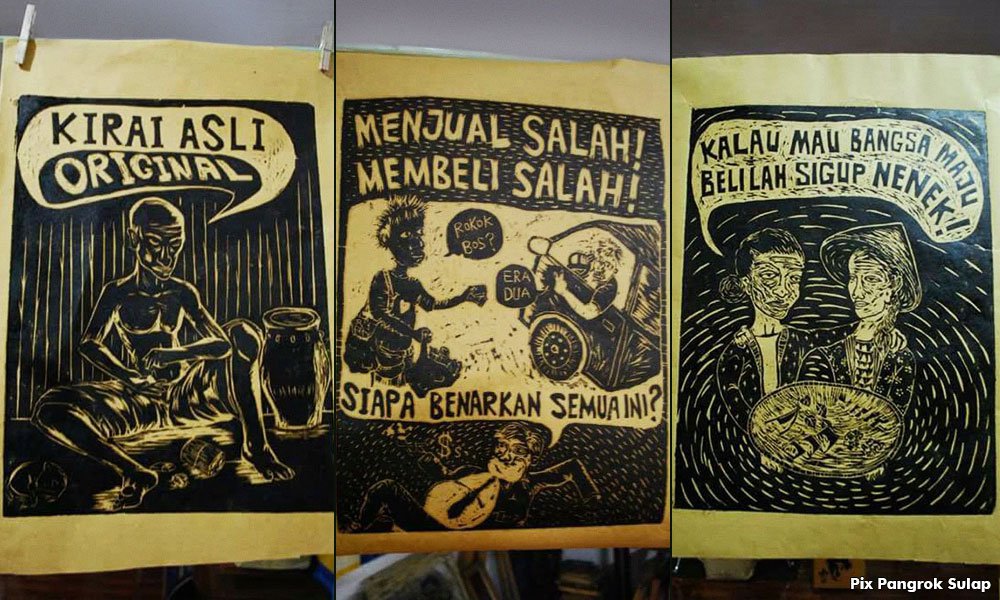

“With all our work, we try to amplify the unheard voices of the Sabahan people so that the public can understand the reality on the ground. We work with our community here in Sabah a lot and we see so many problems, we don’t make it up,” Jerome says.

Used to paint fungi in forest

Before joining the collective, Jerome worked as a forest ranger at the Danum Valley Conservation Area in Sabah.

“I was involved in many art projects at the time but the problem was I needed money to survive. My father was a ranger all his life and I used to follow him when he worked. So I chose to be one too, and it turned out to be the best time of my life.”

Jerome loved everything about the jungle. From the giant lush trees to the insects and the fungi. Especially the fungi.

“The virgin forests in Danum are really different, what got me most excited is when I would find so many types of mushrooms and fungi not seen anywhere else. It was like a new adventure everyday, I never got bored. It felt like I was in heaven.”

He even painted the fungi in secret but was eventually found out by his superiors. They were so impressed they transferred him to headquarters to make artwork for the forestry department’s monthly publication.

“I left because I didn’t like working in an office,” he says, throwing his head back in a chuckle.

Art for the people

So how did a quiet nature lover turn into a rebel artist?

Jerome looks behind him and nudges Rizo Leong, another member of the collective and a childhood friend.

“Jerome used to draw comics on the table in class! He was a vandal! We always got into trouble together and we promised each other we would make art together one day,” Leong (left in photo below) chips in.

Many years later in 2010, the two friends reunited over that promise and formed Pangrok Sulap with a few other artists.

Inspired by the Indonesian punk rock collective Taring Padi, they decided they wanted to make art about social issues faced by their community in Ranau, Sabah.

They first made three woodcut posters protesting how local authorities were forcibly confiscating traditional homemade cigarettes sold by old folk in Ranau, Sabah.

The collective also made a series of woodcuts commemorating the mountain guides who died saving hikers during the Mount Kinabalu earthquake in 2015 - many of the guides who perished hailed from Jerome’s hometown of Ranau.

“Through woodcuts and the goals of the collective, I developed a new way to express myself. I realised art could be used to give attention to certain voices we don’t usually hear. I realised art was not for art’s sake but could have this impact for the people of Sabah,” explains Jerome.

Leong and Jerome say the collective is now focusing on organising community art programs in Sabah but are open to exhibiting their work only with “collaborators who understand our work”.

Besides running the arts centre and making woodcuts, Jerome facilitates community art programmes on behalf of the Malaysian Foundation for Innovation.

The foundation found out about his work in the arts and offered him a grant to run art programs with villages across Sabah. He also travels to bring home skills to help the villagers be self-sustaining.

“I came to (Kuala Lumpur) learn and master how to make paper from the banana trunk so I can teach the process to village folk here in Sabah. If they can generate an income from making paper, they will be able to be more self-sustaining.”

Jerome’s conviction reverberates through the computer screen.

“As artists we have a role in our community. I want to make art for the people. I want to make others understand what people in Sabah go through.”

“Good art is art that is good for the people.”

MALAYSIANSKINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.

Previously featured

Doctor bids to destigmatise mental illness

The ‘Puan Sri’ who fights for the environment

I’m no freak, says ‘outsider artist’ Rahmat Haron

The real 'Tauke' of Malaysian football

Zunar - the makings of Malaysia’s most dangerous cartoonist

Gerai OA empowering Orang Asli women through craft

How four teens cook up a solution for food wastage

Organic farmer now lighting up Borneo's interiors

A crusader in crutches has hunger for Bersih 5

Tackling medical myths in Malaysia

M'sia's first blind lawyer not losing sight of importance of education