book review March 8, 2008 as many of us are aware, marked a sea-change in Malaysia’s political landscape or, to borrow the current buzzword, a political tsunami.

Pakatan Rakyat took over the reins of power in Penang, Kedah, Perak, Selangor and retained Kelantan. To top it all, the opposition coalition deprived incumbent Barisan Nasional (BN) of its coveted two-thirds majority in Parliament.

Pakatan Rakyat took over the reins of power in Penang, Kedah, Perak, Selangor and retained Kelantan. To top it all, the opposition coalition deprived incumbent Barisan Nasional (BN) of its coveted two-thirds majority in Parliament.

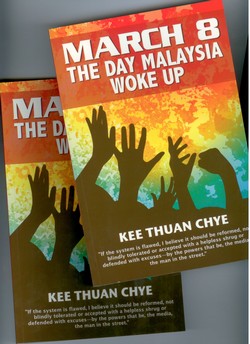

Kee Thuan Chye’s latest book, ‘March 8: The Day Malaysia Woke Up’, is not only an endeavour to document the significant changes that had taken place in Malaysia prior to and since the March 8 general election and the hopes of Malaysians who dream for more meaningful changes thereafter.

This 325-page volume also serves as a useful reminder to political Rip van Winkles who appear to remain clueless or, worse, are living in denial of the new political environment - judging from, for instance, the way certain politicians still play the ‘race card’, ignore underlying causes of widespread discontent, mistreat minorities or browbeat critics.

Central to the concern of journalist, dramatist and writer Kee

(left)

are (a) the vital changes that have taken place in Malaysian politics as well as (b) the hopes of ordinary Malaysians for a better Malaysia that celebrates ethnic, cultural and religious diversity, and upholds dearly the universal values of compassion, fairness and justice and democratic principles.

Central to the concern of journalist, dramatist and writer Kee

(left)

are (a) the vital changes that have taken place in Malaysian politics as well as (b) the hopes of ordinary Malaysians for a better Malaysia that celebrates ethnic, cultural and religious diversity, and upholds dearly the universal values of compassion, fairness and justice and democratic principles.

These two factors predictably manifest themselves in the way the book is largely structured: Part 1 is on ‘Change’ and Part 2 is on ‘Hope’.

Large portions of Part 1 constitute an attempt to understand the reasons and circumstances that led to the overwhelming political change on March 8.

Hence, there are pieces in this section that remind us of the ‘flagrant arrogance’ - to borrow a phrase from Ooi Kee Beng (

right

) in the book - of certain ruling politicians to the extent of becoming insensitive to legitimate grievances of the minorities, the weak and the marginalised as well as constructive criticism from civil society.

Hence, there are pieces in this section that remind us of the ‘flagrant arrogance’ - to borrow a phrase from Ooi Kee Beng (

right

) in the book - of certain ruling politicians to the extent of becoming insensitive to legitimate grievances of the minorities, the weak and the marginalised as well as constructive criticism from civil society.

Thus, it makes sense that this section allocates writings such as the one by Helen Ang, who highlights the significance of the now outlawed Hindraf movement that succeeded in attracting some 30,000 Indian Malaysians onto the streets of Kuala Lumpur on Nov 25, 2007.

With its rallying cry of Makkal Sakthi (people power), Hindraf managed to tug at the heartstrings of many a Malaysian who can relate to the grievances of particularly the poor and the weak in the Indian community and other marginalised groups.

Ang also writes about the Bersih rally for fair and free elections and fair access to media that was able to draw a crowd of between 40,000-60,000 in this civil society initiative held on Nov 10, 2007 in Kuala Lumpur.

Ang also writes about the Bersih rally for fair and free elections and fair access to media that was able to draw a crowd of between 40,000-60,000 in this civil society initiative held on Nov 10, 2007 in Kuala Lumpur.

The rally was fairly represented in terms of ethnic and class composition and jolted many Malaysians out of their political slumber. The mainstream media generally painted the Bersih rally, as in the case of the Hindraf street demonstrations, as socially and politically disruptive.

Clearly, the way the Bersih and Hindraf had been mistreated and ignored by the authorities only further alienated the government from these marginalised groups. It denied itself these important realities. However, the upside to this is that these rallies had raised political awareness among Malaysians.

Different outcomes

To be sure, the political tsunami didn’t necessarily yield a positive outcome. For example, Yip Wai Fong of the Centre for Independent Journalism reports that a study of Utusan Malaysia between March and April reveals that the Malay-language daily has not adapted to the new political realities.

If anything, the newspaper’s coverage ‘borders on racism’. Yip concludes: ‘To many people who had hoped that the election results would herald a wave of change headed towards more openness and accommodation, Utusan Malaysia’s behaviour might feel like a splash of cold water.’

In contrast, Kee’s interview with Malaysiakini editor-in-chief Steven Gan tells us about the online newspaper whose origins was precipitated by the relentless urge to push the envelope and widen democratic space for the ordinary Malaysians in the face of a number of repressive laws and political harassment.

The news portal played a pivotal role in the coverage of the general election. And to adapt to the new political landscape, Malaysiakini discloses its future plans, such as the opening up of new bureaux in areas outside of the Klang Valley.

Perhaps the highlight of this section is the interview that was conducted with controversial

Malaysia Today

editor, Raja Petra Kamarudin (RPK), who is now languishing in the Kamunting Detention Centre under the unjust Internal Security Act.

Perhaps the highlight of this section is the interview that was conducted with controversial

Malaysia Today

editor, Raja Petra Kamarudin (RPK), who is now languishing in the Kamunting Detention Centre under the unjust Internal Security Act.

Titled, ‘How Big Are Your Balls?’, this chapter is the outcome of a four-and-a-half hour interview. It traces the punishing daily routine of the irrepressible editor RPK, his run-ins with the authorities, and his thoughts about PKR, PAS, the Islamic state, post-March 8 BN, race politics, Ketuanan Melayu (Malay supremacy), the NEP, Anwar Ibrahim and Pakatan Rakyat, among other issues.

Justice and education

In Part 2, various people are given voice to express their dreams and ideas of what a new and better Malaysia ought to be.

An issue that Malaysians have been trying to grapple with in their attempt to move forward with the times, especially after March 8 and also with the onslaught of globalisation, is the NEP.

Hence, there are two chapters that cater to a certain Yazmin Azman (‘Do We Really Need The NEP?’) who’s troubled by what she considers as the policy’s flaws: ‘What should be a system based on helping the weak and levelling the playing field has become the modern equivalent of an apartheid nightmare.

Academic Lim Teck Ghee (‘Enough of the NEP’) revisits, via an interview with Kee, the NEP and its negative implications in society.

Academic Lim Teck Ghee (‘Enough of the NEP’) revisits, via an interview with Kee, the NEP and its negative implications in society.

An essay, ‘For the sake of the common people’, penned by academic and human rights activist Kua Kia Soong, constitutes a wish-list for BN and PR and possibly for many other Malaysians.

Kua calls for the abolition of the ‘racially discriminatory NEP’; a “culturally fair education policy”; repeal of the ISA; reform of the police force and the judiciary; a review of the PPPA and OSA and an introduction of the Freedom of Information Act; reintroduction of local government elections; land tenure for indigenous peoples, urban settlers, farmers and titles for new villages; and an introduction of a state water policy, among others.

Justice is one of the cornerstones of a democracy, and therefore it has become a burning issue among many Malaysians especially since the judicial crisis in 1988.

Law academic Azmi Sharom

(right)

addresses the importance of reform in the judiciary in his chapter, ‘We need to correct, correct, correct the Judiciary’. He traces the origins of the problems that have been afflicting the not-so-independent judiciary since 1988.

Law academic Azmi Sharom

(right)

addresses the importance of reform in the judiciary in his chapter, ‘We need to correct, correct, correct the Judiciary’. He traces the origins of the problems that have been afflicting the not-so-independent judiciary since 1988.

His essay is followed by an interview with former de facto law minister Zaid Ibrahim who also touches on, among other important issues, the question of judicial reform.

Local universities are not spared either in this book as they are perceived as having an important role to play in nation-building. Academic and writer Azly Rahman in ‘Let a hundred flowers bloom’ critically assesses the state of higher education in Malaysia.

A remark he made is instructive as it urges us to revisit the original meaning of university: “The core business of students and scholars is to dissent, to differ, and to deconstruct prevailing truisms.”

It’s worth quoting him further: A university “is a place wherein the universality of ideas must reign, guided by philosophies that bring humanity closer to a more meaningful democracy”.

“A university is not merely a diploma mill and a production-house of academic Taylorism. It is not an institution to put a Quality Control stamp on the minds of students so that they may become merely good workers in a TQM-inspired company. It is not a game of production and reproduction and schooling the mind into total submission.”

Media play vital role

Like universities, the media are also seen as having a vital role in nation-building. Hence, this section of the book allocates space for four pieces on the issue of the traditional and new media as well as media freedom.

The emergence of the new media receives varying degrees of optimism from the writers concerned in relation to a larger social context which still harbours laws that curb media freedom.

Recent developments in Malaysia’s media industry since March 8 point to the relevance of the discussions that prevail in this book.

Personalities who are directly involved in the political sea change are also included in this volume to enable readers to dig into the minds of selected politicians who have the potential of making a difference in Malaysian society.

Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng and PAS vice-president Husam Musa

(right)

were interviewed for this very purpose.

Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng and PAS vice-president Husam Musa

(right)

were interviewed for this very purpose.

And consonant with the principle held by Kee, the remaining pages of the book are reserved for ordinary Malaysians to express their hopes and dreams for a better Malaysia. They range from engineer to writer to mother to academic.

March 8 offers a good spread of issues that were sparked by the political tsunami. However, there are a number of dimensions of this phenomenon that have been inadequately tackled or not at all handled by the book. For instance, corruption is one social scourge that has plagued the nation and Malaysians are still reeling from it, and yet it merely occupies mere three pages (‘Corruption 101’).

Similarly, the much-touted concept of ‘Bangsa Malaysia’, one that supposedly helps foster inclusiveness and promotes unity in multiethnic and multicultural Malaysia, only receives scant treatment.

Similarly, the much-touted concept of ‘Bangsa Malaysia’, one that supposedly helps foster inclusiveness and promotes unity in multiethnic and multicultural Malaysia, only receives scant treatment.

Deeper reflection on this notion is warranted given the increasing interest among Malaysians and the vulgar rearing of the ugly head of racism from time to time.

If Malaysia’s civil society did play an important part in raising consciousness among Malaysians to the point of helping to influence the March 8 electoral outcome, then what is also missing in this volume is a discussion of the political and intellectual contributions of the women’s movement towards this end.

And, finally, while sufficient space and treatment are given to the issue of the media and press freedom, there is no discussion of what has happened to the Chinese and Tamil press since the March 8 political transformation. There’s indeed a gap here that needs to be filled.

Having said that, this volume, published by Marshall Cavendish, makes an important and interesting read as it strives to provide an understanding of why and how the political tsunami struck this nation, and its social and political consequences for the not too distant future.

Equally important, this book is also an acknowledgement of the fact that Malaysians in general do have, if I may sheepishly borrow a term Kee used on RPK, ‘balls’!

MUSTAFA K ANUAR is a lecturer with Universiti Sains Malaysia's School of Communications.