COMMENT | Much of the encomia for Kassim Ahmad, who died at the age of 84 in Kulim yesterday, spoke of his courage in the face of repression of his beliefs.

Kassim exemplified Ernest Hemingway's definition of courage as grace under pressure. He was serene in facing the waves of hostile reaction to his beliefs – save in one instance.

This was when he blamed Anwar Ibrahim for forestalling the evolution of a debate he wanted with critics of his book, “Hadis: Satu Penilaian Semula” (Hadith: A Re-evaluation).

Kassim had wanted the book, which was banned shortly after its publication in 1986, to evoke a debate on the arguments he had adduced for making the Quran – and not the Hadith – as the principal source of Islamic faith and jurisprudence.

The conventional view was that the sources of Islamic jurisprudence were the Quran, Hadith and the general consensus of Islamic scholars. Kassim had argued that the Hadith contradicting the Quran could not be relied upon as a source of Islamic jurisprudence.

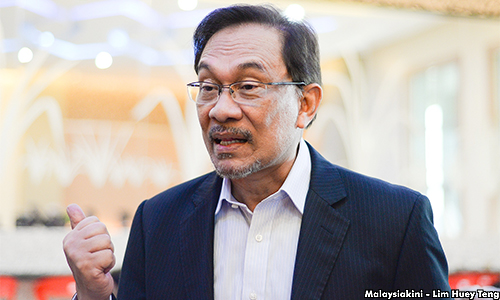

He fingered Anwar (photo), then a cabinet minister, as having played the main role behind the scenes to stop any debate on the book from taking place, specifically a debate with the Malaysian Muslim Youth Movement (Abim).

The debate didn’t go ahead. Kassim, ever willing to debate his disputants, blamed Anwar for this.

Anwar was then seen as the go-to Islamist in government, having been Abim leader from the early 1970s, before mutating from government critic to collaborator in the drive that begun under then prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad in 1982 to inject Islam into the administration and governance of the country.

From the perspective of the years gone by, this move is now seen as having paved the way for the weakening of the secular underpinnings of the 1957 Constitution inaugurating the country's birth – thus opening the way to what many feared would be the eventual Islamisation of the country, which would have been a travesty of what the country's founders envisaged.

Kassim would remain scurrilous and vituperative on Anwar's alleged role in foreclosing debate on the banned book.

'Amenable, amicable and kind'

The venomous streak that was much in evidence whenever Anwar's name or fate came up in conversations between Kassim and friends who came a-visiting seemed uncharacteristic of the man who was otherwise amenable, amicable and kind.

From the time he graduated from the University of Malaya in Singapore in the late 1950s to the mid-1980s, when he called for a reevaluation of the hadith, Kassim distinguished himself as a thinker who was wont to go against the convention.

From the time he graduated from the University of Malaya in Singapore in the late 1950s to the mid-1980s, when he called for a reevaluation of the hadith, Kassim distinguished himself as a thinker who was wont to go against the convention.

He had espoused the merits of Hang Jebat as the authentic Malay hero, in contradistinction to Hang Tuah as the archetype, in Malay intellectual discourse in the early 1960s.

He introduced “scientific socialism” to Parti Rakyat Malaysia in the mid-1960s when he took over its reins from founder Ahmad Boestamam, and changed the party's name to Parti Sosialis Rakyat Malaysia, in conformity with the Marxist view that their ideology was irrefutable science.

Even when he began to abandon scientific socialism for an Islamic worldview while under ISA detention between 1976 and 1981, it was towards “Teori Sosial Moden Islam” (Modern Islamic Social Theory), the name of the treatise he would pen after being freed, and not towards anything nebulous.

Kassim’s was an intellect that craved certainty for its beliefs, where such certainty is elusive. That was probably why he took an oppositional view of the Hadith, with some of its origins in the mists of times long ago.

Whether it was jousting with national literary laureate Shahnon Ahmad on the role of art and literature in Islamic discourse, or with Islamists on the reliability of the Hadith, Kassim evinced the air of the scientific rationalist.

He had the iconoclast's penchant for challenging orthodoxies, but this yen came with the ideologue’s weakness for certainties.

The French writer Honoré de Balzac knew the type when he observed that “It's not sufficient to be a man; one must be a system.”

TERENCE NETTO has been a journalist for more than four decades. A sobering discovery has been that those who protest the loudest tend to replicate the faults they revile in others.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.