“The most powerful weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

― Steve Biko

BOOK REVIEW | AB Sulaiman’s book, ‘Ketuanan Melayu: A Story of the Thinking Norm of the Malay Political Elite’, cogently defines the agendas of the establishment hegemon and also the pervasive group-think that defines mainstream Malay politics.

AB Sulaiman makes the distinction between “race” and “culture” and examines the “Malay” construct through the racial and religious politics of the day, paying attention to history and lamenting that dissenting voices in the community have always been marginalised.

What is interesting about this book is that AB Sulaiman passionately (as opposed to clinically) disables narratives around what it means to be “Malay”, viewing the Malay culture through an ethnolinguistic lens, among various other social and political philosophies and theories. Do not let this dampen your enthusiasm for the book because AB Sulaiman writes in an easy-going friendly manner, even when offering up political and philosophical “sensitive” issues, to which he devotes a whole chapter.

The most important takeaway from this book is that AB Sulaiman does not make the same mistake that some writers make when discussing Ketuanan Melayu. The writer understands that this is not a tool to unify the Malay polity. Ketuanan Melayu is a tool to divide the Malay polity. The writer makes it clear that the latter purpose is the defining characteristic of this social-political, but most importantly, religious-political construct.

What does this mean in AB Sulaiman’s weltanschauung? This concept is a political tool used to not only marginalise dissenting voices in the Malay community but to monopolise narratives to ensure that the political hegemony of dominant Malay power structures becomes the mainstream narrative of what it means to be “Malay”. This, according to the writer, is why dissenting Malay voices are vilified as “traitors” to the Malay “race” and unIslamic.

Now, some would argue that the beginning chapters of the book that define certain concepts of different modes of thinking, linguistic theories and concepts such as nation and statehood are superfluous, but I presume that the author needs those chapters to set the scene, so to speak, to explore the complex dynamics, historical, philosophical and otherwise, of Malay society.

AB Sulaiman correctly points to the political elite who use this hegemonic tool – Ketuanan Melayu – as a means to not only divide the Malay community but also constrain the rights, responsibilities and aspirations of the non-Malay/Muslim communities. The writer argues that the sacred cows of the Malay community have, in effect, destroyed individualism and created a community that is constantly questioning its relevancy in a changing world, as opposed to adapting to a changing world.

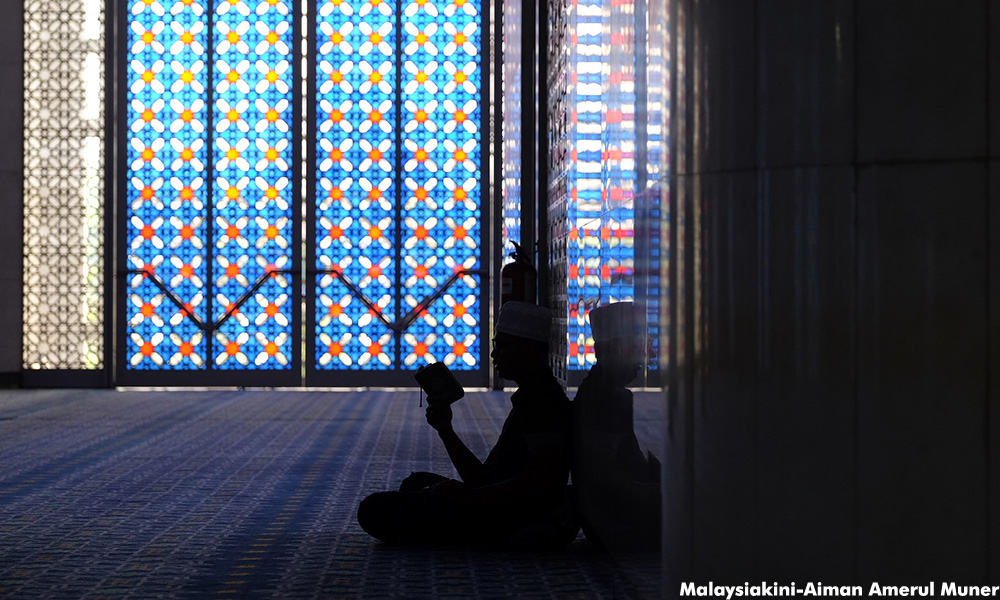

What I like about this book is the fact that the author points to the diversity in Islam as beneficial to religious societies. He makes it clear that the monolithic idea of Islam, as propagated by the state, creates friction between those Malays who want to explore their religion and those who believe that their dogma entitles them to some sort of religious, and in the Malaysian context, racial superiority.

This is important because it reflects why the opposition in this country, for instance, is bound by certain narratives of what it means to be “Malay” instead of encouraging diverse narratives that would mean that the concept of what it means to be “Malay” is not defined by the state.

‘Paradise Lost’

There is a whole chapter in the beginning on the constitutional definition of “Malay”. This chapter is interesting not only because it slays sacred cows but because the author makes no bones of his scepticism of this definition, using scientific and historical counter-arguments to make his case, which is the antithesis of what the political elites do or encourage.

My favourite chapter in the book is ‘Paradise Lost’, a comparison between Malaysia and South Korea in which the author states his intentions clearly – “In this chapter, I want to cite one more result of Ketuanan Melayu leadership showing the link between thinking and patterns of behaviour.

“This time I take two countries, Malaysia and South Korea and compare their relative social, economic and political record of performance from the early 1960s to date. My purpose is simple, how does the Malaysian political entity run on the basis of religion, race and nationalism, compared over time with the South Korean based on democracy and secularism.”

The author makes it clear, though, that he believes that the establishment has deliberately strayed from not only the spirit of the constitution but also engineered a manufactured Islamic revival which is detrimental to the country, but more importantly, detrimental to the progress of the Malay community. He makes it clear that the corruption of the political elites is buried beneath an agenda of Islamic dogma and racial supremacy.

In the author’s words - “Such policies are contrary to the basic principles and tenets of the constitution. For one, the founding fathers like Tunku Abdul Rahman have put on record that Malaysia should be a secular country run on the model of the Westminster form of constitutional monarchy; present policies adopted are running away from these ideals.

“Secondly, such policies are also running away from the ideals of democracy and human rights. So why is Ketunan Melayu running away from historically sound premises of democracy and human rights in leading the nation?”

Why indeed? The answer, of course, is in AB Sulaiman’s book.

S THAYAPARAN is Commander (Rtd) of the Royal Malaysian Navy.