COMMENT | History will show that Malaysia’s early intervention played a crucial role in flattening the curve against Covid-19 this year. The public health threat from the disease is far from over. Numbers globally are rising faster and now well over 10 million, with over half a million who have died from the disease.

Despite Malaysia’s move to recovery after over 100 days since the initial lockdown and increasing complacency, the challenges remain serious, not only for public health but in rebuilding the economy and strengthening social protection.

So far, analyses of the Covid-19 response have centred on the role of the federal government in addressing the pandemic. A first-rate report by Fifa Rahman outlines the strengths of the federal government response. Respected civil society organisations Galen Centre and CodeBlue have also provided excellent commentary and analysis.

In a series of articles looking at Covid-19 from below, I will try to bring attention to areas where Malaysia’s Covid-19 response has been shaped by actions outside of the rubric of Putrajaya.

This first piece looks at the role of state governments. News reports on federal-state relations during the pandemic have concentrated on the contentions over jurisdictions and failures in sharing communication and inclusion (and exclusion) of states on the part of the federal government, especially in March and early May when the movement control order (MCO) was introduced and initially relaxed. The ignored story has been the actions taken by state governments to save lives.

The dominant narrative of Covid-19 governance is that centralised top-down governance contributed to Malaysia’s success, that the efforts of a few men saved the country. While leadership has been important, especially from Health Ministry director-general Hisham Abdullah (below), this from-the-top assessment is incomplete.

A state government lens allows us to better understand the role of local knowledge, sensitivity to local communities needs and conditions, the adoption of new and more inclusive scientific approaches, targeted allocation of resources (both fiscal and human) and how less politicking made a difference.

States that stand out in their responses include Penang, Sabah, Sarawak, Selangor and Terengganu. All of Malaysia’s state governments, however, have made important interventions (often unreported and unappreciated) and deserve more recognition of their efforts; these measures are an important part of the fabric of the mask that has protected Malaysians.

Federal-state cooperation and ambiguity

Officially health is a ‘federal’ matter, with the Health Ministry leading on health matters. In practice, however, there is considerable coordination between health officials and state exco members who are responsible for public health. Repeatedly, state officials speak of cooperation over confrontation and inclusion over exclusion in practice – in contrast to the messages of news reports.

The reason is simple - most of the hard work is done by civil servants who work around politics. There are long-standing trust networks in this sector. Consistently, state health directors – many of whom are women – have fought hard to maximise resources and work around political obstacles. They are experienced and have been facing public health problems for some time.

Sabah’s Health Department director Dr Christina Rundi (below) is illustrative – she has admirably grappled with challenges of malnutrition and the state’s outbreak of polio earlier in the year before facing Covid-19. Those working in health care are professionals and trained to put people first – even when some politicians do not. This is not to say that things always run smoothly – there are differences, some tensions and territorial battles – but these pale in comparison to the takedown culture of Malaysian politics.

The main federal-state ambiguity in Covid-19 implementation arises from areas outside of health – the control of public spaces in the form of rents, licences and land management as well as the management of religion. Jurisdiction battles warred over when to open car workshops, hardware stores, and whether to hold night markets. Quietly, state religious authorities issued their own guidelines.

The states that most used their different constitutional powers were Sarawak and Sabah. Sarawak regularly issued and gazetted their own circulars, and both states imposed their own immigration regulations. Sarawak went as far as using its own listing scheme on cases, making coordinated comparisons with the federal government somewhat challenging. The Borneo states used Covid-19 to showcase their greater autonomy, while differences in Peninsular Malaysia were more about projecting difference from (or support for) the current Perikatan Nasional (PN) federal government.

For citizens, the ambiguities were often confusing, especially when they contradicted federal announcements. Rules on when and how to enter Sabah changed regularly, for example. None of the jurisdiction differences was legally challenged (so far), and the general pattern was while hours of local services varied in states, most measures generally moved toward the federal standard.

Testing and tracing: adopting technology and science

While areas of reported contention ebbed, the measures by states on the ground went in the other direction. States expanded and targeted public health care initiatives and Covid-19 relief measures. Here is where the real meaningful differences are.

One important area where this happened was testing as state governments engaged and supported targeted testing. Selangor’s Covid-19 Task Force, for example, used analytical modelling to identify ‘red zones,’ capitalising on an approach that was tied to science and more activist interventions. This involved more proactive testing in places such as old folk homes and in potential cluster sites.

These models built on local knowledge. Selangor state paid for the additional tests. Sabah also was active in seeking out additional test kits, using ties to Singapore to obtain them and receiving help from federal authorities in their distribution. Penang also provided funds for testing and medical equipment, although, as occurred in almost all of the states, the federal government’s strategy of using targeted testing (to maximise resources) predominated.

Some states also developed their own tracing applications – Penang (PGCare), Sarawak (CovidTrace and Qmunity), Selangor (SELangkah), Sabah (Sabah Trace), Terengganu (Masuk.la) and Johor (Jejak Johor).

Sarawak led the charge in adopting tracing technology, following Singapore, and introduced two different apps, one for authorities and another for Sarawakians. They also introduced a wristband requirement for those entering the state, a move that has been the most controversial of all the initiatives. Selangor and Penang, also started with more technology/scientific orientations in their Covid-19 approaches, were right behind Sarawak, with the other states adopting state-based tracing app later on.

While these state-based apps have raised eyebrows as important questions persist about privacy protections and differences regarding their effectiveness, they complement tracing apps at the federal level Gerak Malaysia and MyTrace and MySejahtera, which are used by some of the states lacking their own software. Some argue the state applications are more effective – but the jury is still out on this.

The state-based apps tap into the broader global trend that recommends local, decentralised applications for the most effective contact tracing, building on the idea that sharing local information is best done locally, and usually these localised apps offer more protections for data and misuse by authorities – although this issue remains inadequately discussed in Malaysia to date.

The tools at the state level, however, do allow health officials to be more proactive in addressing Covid-19, to stop potential clusters from emerging. States such as Selangor, for example, have been able to develop their own analytical models using technology for more proactive interventions.

Sharing information and outreach: embracing collaboration

Another important area where states have strengthened government responses to Covid-19 is in communication. While the Health Ministry is rightly lauded for its sharing of information daily, notably case numbers and preventative public health information, state governments have enhanced this by translating health and lockdown information into more languages, creating educational videos, expanding outreach education programmes, establishing hotlines and even a website.

Penang has the most extensive engagement in public communication with 24-hour hotlines and its own website. Chief Minister Chow Kon Yeow also regularly gave briefings on Facebook, while Sarawak local government and housing minister Dr Sim Kui Hian made daily updates on his Facebook. Selangor and Sabah officials were similarly more engaged in sharing public information and answering questions. These actions played an important part in countering disinformation, especially in the early period of the pandemic.

Outreach efforts also included local government officials. In Penang, over 5,000 staff with the two town councils were mobilised to monitor compliance during the MCO. Selangor and Sarawak did the same by bringing in local authorities, especially around cluster areas. Sarawak’s approach was to prioritise containment in urban areas, to prevent the spread into rural communities where medical facilities are not available.

In more rural areas elsewhere, district officers engaged in sharing information and coordinating local contact-tracing with health officials. For example, in Kelantan, local officials were essential in contact tracing and follow-ups, one reason this state maintained a lower transmission rate. Perlis also similarly used personal ties and trust networks in contact tracing, helping establish itself as the first green zone state in April. Local trust networks matter and these were often best harnessed at the state and local levels.

A key part of the local mobilisation involved the relationship with civil society. Here is where there are sharp differences among states, as some state governments were more willing to engage with civil society than others. Sarawak, Sabah, Selangor and Penang in particular worked to bring in local medical practitioners, mobilise charity networks and donations and fostered more collaborative private-public sector partnerships. Kelantan and Terengganu worked through religious organisations, both government and private.

Much of the donation efforts remained private, aiming to fill needs not being addressed by either the federal or state governments, but the relationship to civil society varied in that state governments encouraged and welcomed different forms of civil society participation more than others.

Spending: Fiscal interventions and limitations

States have also differed in how they have used their responses to address Covid-19. Some state government officials such as those in Selangor, Penang and Terengganu took pay cuts or in some cases, donated their month’s salary altogether.

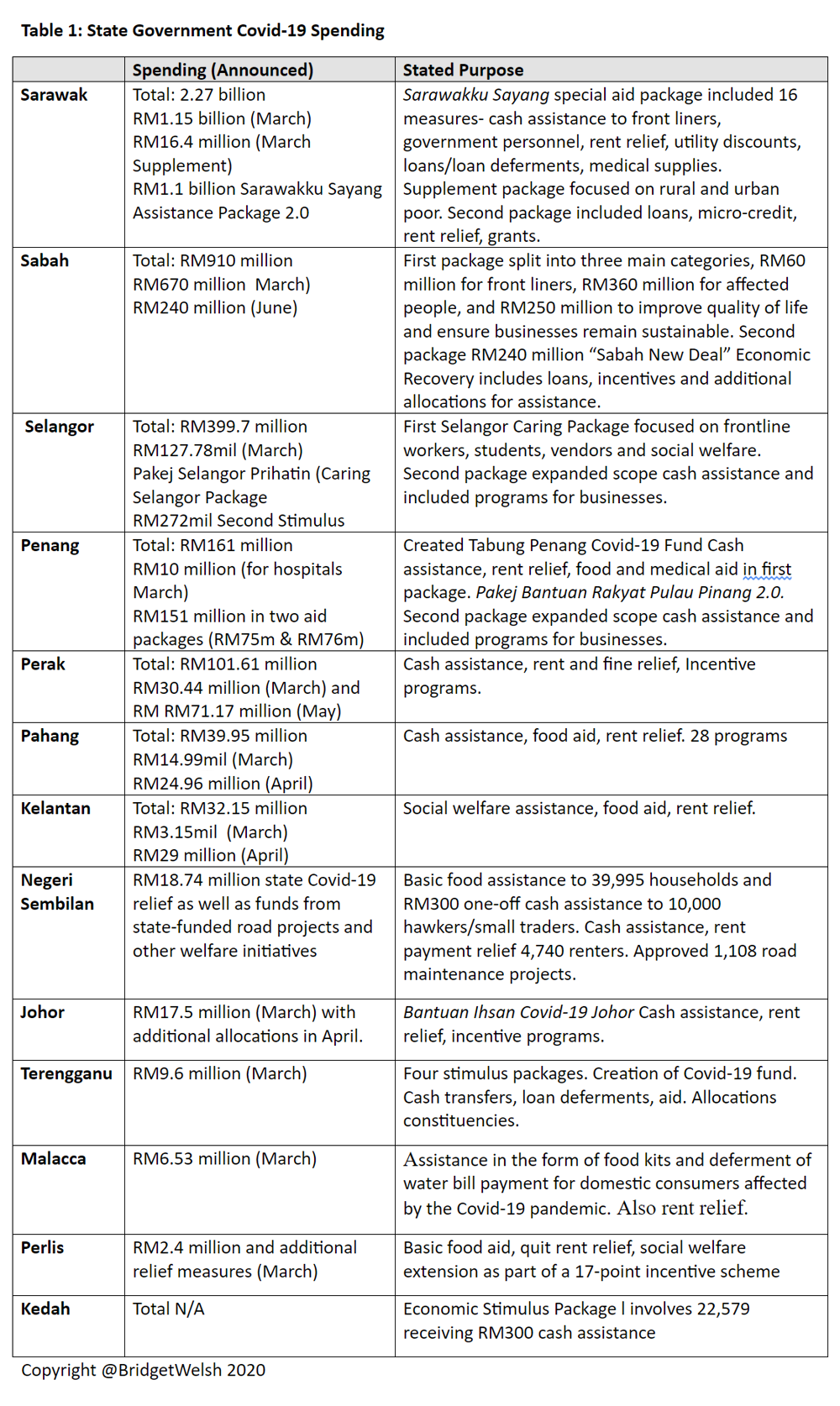

A major difference has been the amount of money promised. Drawing from news reports in the past three months, states have promised over RM4 billion in a variety of relief measures and economic incentives, with the Borneo states allocate far more spending than states in the peninsula, where Selangor and Penang make the biggest allocations.

The reports on spending detailed below should be treated with some caution. These are reported figures for “Covid-19”, so they do not necessarily include spending that might be taken from other programmes. Second, they are allocations, rather than actual amount spent – which may in fact not be spent at all or in the case of many of the federal programmes, oversubscribed out of need.

Finally, as in all spending programmes, the devil is in the details. Many loans are actually scheduled to be paid back and not spending at all, for example. Some patronage projects have been embedded in the spending as well. This said, the numbers do showcase how much states have been a part of Covid-19 governance.

While states that have allocated more funds to Covid-19 should be lauded, it is also important to appreciate the fiscal constraints facing state governments. States have limited sources of revenue, primarily from state businesses/investments, land and rentals (for an excellent report see IDEAS Tricia Yeoh’s recent study).

Poorer (and less populated) states have less money to spend – evident in the pattern of Covid-19 spending. Many are highly dependent and indebted to the federal government, which has been more proactive in recent years in asking for payments in this era of post-1MDB forced austerity. Terengganu, for example, asked the federal government to defer its payments on loans due to the federal government to allow it more funds to be spent locally on Covid-19. The pattern of spending brings home the disparities different state governments face in carrying out their work.

Special focus areas: Vulnerable communities, local businesses and local needs

Fiscal limitations shaped state governments interventions. It is thus not a surprise that the common

threads involve rent relief, basic food aid and loan deferments – all tied to state sources of revenue.

States are maximising the resources they have on hand and building on their established bureaucratic agencies. Some states, such as Terengganu and Kelantan rely more heavily on allocating relief through constituency representatives, while those with more developed social welfare programmes at the state level and greater use of e-government, such as Selangor, allow citizens more individual access. How the states engage the public shapes who gets the aid.

The spending allocations also reveal that certain groups were favoured by state governments more than others – front liners (including civil servants in many states), those already traditionally targeted for cash assistance (e.g. fishermen, those on state social welfare as examples) and those relying on state services, e.g. local traders and hawkers generally received priority.

The level of inclusion in social welfare lists at the state level varies considerably. One consistent complaint has been that businesses, especially small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have not received enough help, echoed at the state level as well.

Yet, there are important differences in the state allocations compared to those at the federal level – as many state governments have been more open to engaging vulnerable and marginalised communities. Almost all of the states recognised vulnerability but differed in who they consider to be vulnerable and their engagement. The Terengganu, Penang and Selangor governments, for example, housed the homeless.

Selangor government allocated RM297,050 to ease the burden of 5,941 heads of Orang Asli households, while elsewhere the outreach to this community was almost exclusively private donations or through the limited federal support. Selangor also housed foreign workers, which reduced the health risks for Malaysians as a whole. This humanitarian approach contrasted sharply with the roundups and arrests that dehumanised migrants.

At the state level, we see initiatives that show sensitivity to those affected by Covid-19 directly. Johor offered funds to those who caught the disease and lost loved ones. Selangor allocated RM1 million for mental counselling and practical training, addressing the psychological and economic realities of the ‘new normal’.

Sabah put aside RM20 million for education and innovation. The Borneo states also intervened in areas of food supply. The Sarawak government, for example, spent RM90,000 to buy 39 tonnes of agricultural produce including fruits and vegetables from farmers to solve the problem of vegetable dumping in April. Sabah focused on food supply as well, recognising the challenge of food security, which were especially acute in these large states when regular transhipment routes stopped.

State governments were on the front line in recognising the needs of local businesses. The Penang government engaged the factories to assure those that qualified as essential services remained open and received assistance to do this. Penang state also has put in place a ‘Tourism Penang Next Normal Task Force’ proactively working with this sector hard hit by the pandemic. Terengganu worked with the oil and gas sector to put in place procedures for the oil rigs and other industrial sites.

Johor continued to press for a solution to the issue of travel to Singapore, as many Johoreans rely on going over the border for their income. Companies in Johor have had to adjust to new demands in the workforce locally as a result of changes in labour and supply routes – with have involved state government engagements. Johor, Kelantan and Sabah have grappled with managing floods during Covid-19 as well.

Looking at the state numbers

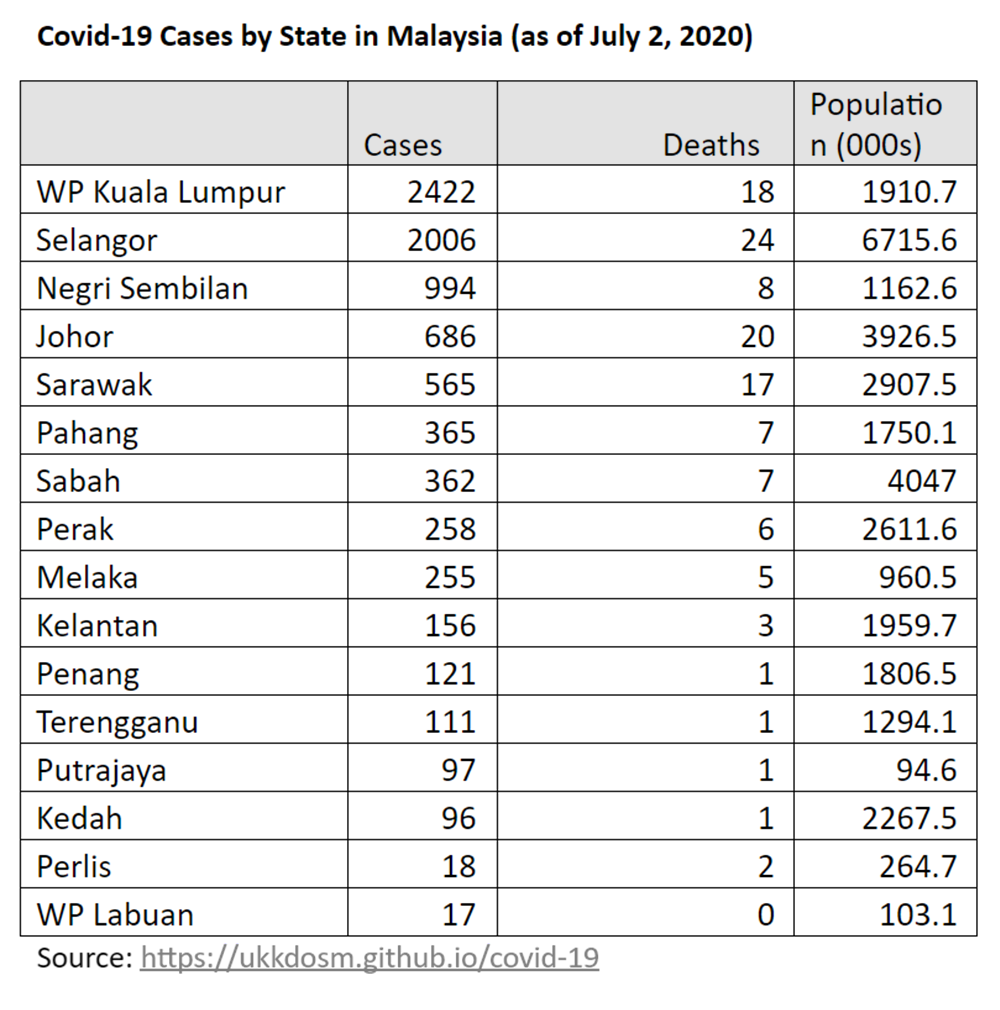

Data produced by the Health Ministry on cases by state/region illustrate the different experiences on the ground. The numbers show that every state has been affected, and Covid-19 clusters have happened and can happen anywhere. It is important to appreciate that the case numbers should not be treated as a competition, and they do not fully capture the varied efforts of states to mitigate the crisis. We have learned that trajectories shaping Covid-19 are the product of many factors. Also, these numbers reflect targeted, rather than more comprehensive testing.

Nevertheless, the data by states does point to some interesting observations. The highest number of cases to date is in the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur. This is not surprising as it is Malaysia’s biggest city. It is also a place without a state government. Kuala Lumpur is close to Selangor - equally urbanised and even larger in population – yet it has fewer case numbers. In fact, all the areas that are federally administered have higher cases for their population and territory than other areas. The absence of a state government makes a difference. Local interventions are important.

The numbers also show how impressive the interventions have been across Malaysia. Penang – highly urbanised – reports only 121 cases, and one death (as of July 2). Sabah, Sarawak, Kelantan, Terengganu, Perak and Kedah numbers given the population size are also outstanding. Ten states have been fortunate to have their numbers of those who have passed on in the single digits.

Rethinking Assessments of Covid-19

These efforts would not have been possible without a broad collaborative effort – one in which state governments played an integral part.

Their roles have not always been perfect. Responses at the state government level do suggest that political infighting and politicking did initially distract state officials from setting out relief programmes, but overall, these delays were overcome and bypassed in some cases by professionally-trained bureaucrats and the shared goal of addressing the risks of Covid-19.

The Covid-19 experience also shows that states that led in interventions provided examples for others to follow. We hear regularly about conflict, failures and shortcomings – and these are there – but examining the state lens for Covid-19 highlights collaboration, successes and learning. It brings to the fore that the Malaysian government is not just top-down, run by a few men, but made up of many people who are putting Malaysians first.

It is noteworthy that many state assemblies actually met and engaged different perspectives of Covid-19, something that has yet to happen at the federal level. We also see that states that engaged professionals, science and technology and those that adopted more people-oriented and interventionist approaches contributed to Malaysia’s Covid-19 success.

Analyses of federal-state relations in Malaysia generally emphasise the need for decentralisation, the push for autonomy in a context where federal power is overly dominant. Covid-19 shows that state governments can play their own roles by harnessing local networks and knowledge, complementing federal efforts. While some federal-state politicking, competition and election considerations did drive, unlike at the federal level, however, they largely enhanced government interventions. Outside of the public posturing collaboration predominated.

Sarawak, Sabah, Selangor and Penang deserve special recognition for their early and broad interventions, with Terengganu also responding early on in innovative ways despite less resources at its disposal.

No question, the actions of many state governments can go further and be improved on. As with Covid-19, there remain more challenges ahead and lessons to learn. The Covid-19 experience suggests that there is a need to rethink Malaysia’s success, to recognise that interventions from below matter.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur.

The author would like to thank the state officials who shared their insights and were gracious with their time.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.