COMMENT | Political parties in Malaysia and the voting public would be better off if our institutions, narratives and norms can be adapted to suit Malaysia’s new normal of having coalition governments formed by parties of similar strength.

Appreciating the prospect of not having a single dominant party in the foreseeable future would help us to consider seriously how we are to achieve stable governments, how we are to deal with the problem of partners fighting over who is to become prime minister, and how we are to help the voting public decide on what sort of coalitions to support.

Gone are the days of a single dominant party winning nearly half the seats in Parliament. The high point for Umno was in 2004 when it won 49 percent of the seats in Parliament, almost managing to form a government without the need for partners.

Below is a list illustrating how Umno, once-dominant party, had been faring since 1969’s general elections.

Year – Seats Umno won/total number of Parliament seats (Umno's percentage)

1969 – 52/144 (36)

1974 – 62/154 (40)

1978 – 70/154 (45)

1982 – 70/154 (45)

1986 – 83/177 (46)

1990 – 71/180 (39)

1995 – 89/192 (46)

1999 – 72/193 (37)

2004 – 109/219 (49)

2008 – 79/222 (35)

2013 – 88/222 (39)

2018 – 54/222 (24)

In the next general election and in subsequent ones, I do not foresee any single political party in Malaysian politics winning more than 70 parliamentary seats. In fact, with Umno, PAS and Bersatu on the same side of the political divide, I will be very surprised if any of them contests more than 70 seats in the peninsula.

Of the 165 parliamentary seats in Peninsular Malaysia, the Perikatan Nasional parties – Umno, PAS and Bersatu – will most likely contest a total of 135 seats and not more than 140 seats. The remaining 25 to 30 seats are likely to be left to MCA and MIC to contest.

The distribution will probably be 60 seats for Umno, 40 seats for PAS and 35-40 seats for Bersatu.

In any case, it is very unlikely that Umno will go for more than 70 seats in the peninsula and even if the seats in Sabah contested by Umno are taken into consideration, the total figure will still not be too far off the 70-seat mark.

On the opposition side, if a one-to-one deal is achieved among all anti-PN parties, including Pakatan Harapan parties, Warisan and forces aligned with Dr Mahathir Mohamad, there would also not be any party contesting more than 70 parliamentary seats in the peninsula.

What this means is that in the foreseeable future, all parties that intend to form governments will have to learn to accommodate their partners in a sustainable manner.

'Presidential prime minister'

During the Sheraton Move, the reason the Harapan centre was not able to hold can be partly attributed to the fact that the key players had, and still have, an outdated understanding of prime ministerial powers.

During Mahathir 2.0, these powers were defused to a certain extent compared to Mahathir 1.0, to Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s period or to Najib Abdul Razak’s regime. First, the budget for the Prime Minister’s Department in 2019 was half of what was the case for Najib’s 2018 budget. Second, the economic function of the Prime Minister’s Department was moved out and placed under a separate ministry.

Third, two dozen agencies from public transport to Biro Tatanegara were either abolished or transferred to other more related ministries to heighten consistency and expertise. Last but not least, then prime minister Mahathir and the cabinet gave Parliament space to operate and to implement reforms.

No doubt, many features of the old “presidential prime minister” structure remained in place.

During its tenure, the Harapan coalition government was not able to respond and adapt to the fundamental question of the new political era that it had so brilliantly created: how to ensure that coalition partners remained satisfied and continued to stay in the coalition even if their party leaders were not the prime minister.

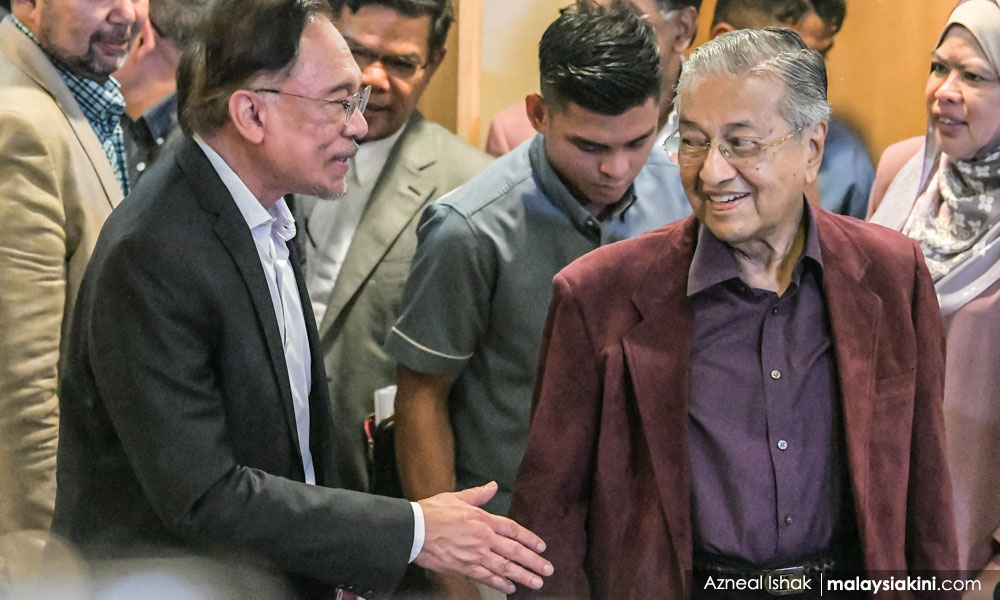

Put simply, during the Harapan government’s rule, the most important political challenge was to re-assure Mahathir’s supporters that an Anwar premiership would not be detrimental to their political standing and, conversely, to Anwar’s supporters that they could co-exist during Mahathir’s premiership. Alas, we failed.

Harapan’s recent effort to reclaim government failed - despite it having 109 seats on the opposition bench - due in large part to the question of the prime ministership. Most political actors are still imagining the premiership to be the pinnacle of all power.

In a democracy living under fast-paced social media scrutiny, the prime minister not only has to convince leaders in his coalition of the benefits of his leadership, but he also has to convince supporters of all parties in his coalition that he can maintain a favourable public perception on most occasions and that he can lead them to electoral victory at the end of each term.

Extremely weak

The prime ministership is no longer the blank cheque as it was in during Umno’s long reign. A prime ministerial aspirant, be it Anwar Ibrahim or Shafie Apdal, needs to assure his or her coalition partners that the leaders of these coalition member parties do not need to be prime minister to remain comfortable in the coalition.

Muhyiddin Yassin uses salaried GLC posts to buy support from the MPs in his hastily constructed coalition. Such bribes may satisfy the MPs personally for a while. But the rest of his supporters are left with little or no gains. Most importantly, they do not see Muhyiddin having much to do with their electoral fortune. Indeed, PAS and Umno supporters are quite convinced that they can win elections without Muhyiddin. Muhyiddin also knows that the leaders in his party must have winnable seats to contest or they face annihilation.

Therefore, the foundation for the coalition that will have Muhyiddin as prime minister is extremely weak and can easily crumble at any time.

The fact remains that PN is a coalition put together for a political coup, and it remains inescapably true that Umno, PAS and Bersatu are electoral competitors. The three are now cramped on the same side of a political divide that is based on an exclusivist racial ideology.

They are making an assumption which can be proven wrong quite easily, which is that Malays will vote for any Malay party without caring whether its leaders are corrupt or not, and whether or not it champions policies that are good for their children.

But then again, PN has little choice but to go into the next election with that assumption. A rude awakening awaits them if they continue taking the Malays for granted.

Being in the corner that they have racially painted themselves into, the Sheraton Move plotters find themselves giving away all the “Others” to their opponents. They assume, or are obliged to assume, that the rest are not significant if all Malays vote for PN.

LIEW CHIN TONG is a senator and ex-deputy defence minister.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.