COMMENT | At a press conference on Oct 29, held to launch the “I Lite U” lighting initiative in conjunction with Visit Malaysia Year 2026, Housing and Local Government Minister Nga Kor Ming was asked by an Utusan Malaysia reporter why the project slogan was in English rather than Bahasa Malaysia.

After responding, Nga (above) reprimanded the reporter, saying, “Jangan jadikan ini satu isu” (don’t make this an issue), and demanded to know which media outlet the reporter represented.

When the reporter replied that he was from Utusan, Nga’s tone hardened. He said sharply:

“Utusan Malaysia. I will remember. I will call your chief editor. I don’t want you to come here and highlight the thing, destroy the entire thing. I will hold Utusan... I will call your chief editor. Alright, because this is national interest.”

Nga’s response prompted criticism from media organisations, academics, and politicians.

Even Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil revealed that the cabinet had discussed the matter.

Nga later gave a perfunctory “apology” during an event in Ipoh, saying: “If any members of the media were offended by my remarks, I retract them and apologise, so that we can focus on efforts to rebuild our beloved nation.”

For those who have worked in the frontlines of journalism, it is an all-too-familiar sight to see those in power reprimand reporters or ask, “Which media are you from?” during press conferences.

Nga is neither the first nor will he be the last to behave in such a way, and it is not only senior politicians who do so.

Age-old problem

Back in the mid-1990s, when I was still a rookie reporter, I was once assigned to interview a senior lawyer who had just been appointed as a judicial commissioner.

During the interview, I asked several questions about judicial independence. When the interview ended, he told me, “I know your editor-in-chief very well.”

The implication was clear: You’d better be careful how you write, or your editor will deal with you.

So, are the remarks such as “I will call your chief editor” or “I know your editor-in-chief very well” an interference with press freedom?

Politicians and cyber-troopers from Nga’s DAP would no doubt insist they are not. But in truth, Nga’s behaviour was a blatant affront to press freedom.

Firstly, such a statement implies that those in power believe they have the authority to silence questions or issues they dislike, whether raised during a press conference or published in the media, and that “calling the chief editor” is a convenient way to exert pressure.

Intimidating reporters

This is an abuse of authority that seeks to draw boundaries around what journalists are allowed to ask.

Secondly, the remark is an attempt to intimidate the journalist not to raise or publish questions and issues that might embarrass those in power.

Publicly rebuking a reporter during a press conference is a form of humiliation, especially if the reporter is new to the job.

In Malaysia’s media environment, half of one’s colleagues might think the reporter was being “immature” rather than rally in solidarity.

When reporters avoid asking “sensitive” questions for fear of similar treatment in the future, that becomes proof of how such reprimanding undermines press freedom.

Nga’s ability to wield such authority and for it to have an effect stems from decades of harsh media controls.

Censorship and power

Media laws have long produced the effects of internalisation (on politicians) and domestication (on the media). As a result, politicians see censorship and media intimidation as routine, while journalists lack the courage to resist.

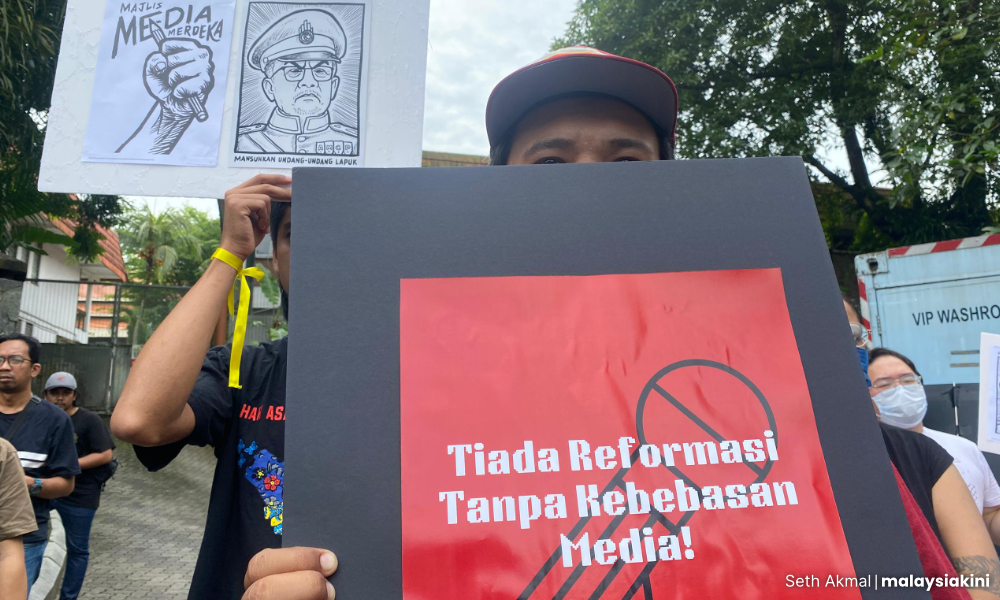

This explains why the Pakatan Harapan government, which came to power under the rallying cry of reformasi, betrayed its manifesto promise to liberalise the media.

Instead of repealing or relaxing restrictive laws, it shamelessly wields the whip of power to commit the same anti-democratic acts it once condemned while in opposition.

Nga, as DAP’s national deputy chairperson, has merely laid bare the political reality that both DAP and other parties lack genuine democratic values.

When in opposition, DAP often invoked freedom of expression and of the press. Yet after coming to power in 2018, the party’s record - threatening to revoke TV3’s licence, suing political opponents for defamation, and invoking the Sedition Act against critics - shows that it now treats those same freedoms with contempt.

Worthless apology

In truth, Nga’s apology is worthless. The only reason he “apologised” was likely because the controversy involved the issue of Bahasa Malaysia usage and cabinet pressure.

His so-called apology implies that he does not actually believe he did anything wrong. The underlying message was just that some people were sensitive and felt offended, and that was the case; he apologised.

Another question worth reflecting on is this: did the journalist in question deserve such treatment just because he happens to be from Utusan Malaysia?

Since being taken over by Umno in 1961, Utusan Malaysia has long served as a political propaganda mouthpiece, notorious for stoking racial sentiment.

Its infamous May 7, 2013 front-page headline, “Apa lagi Cina mahu?”, published two days after BN’s poor election showing, was condemned by DAP and the Chinese community alike.

Still, disliking Utusan Malaysia is one thing; dismissing the harm done to press freedom by Nga and others in the corridors of power is quite another.

Nga may have rebuked an Utusan Malaysia reporter, but what he damaged was Malaysia’s press freedom itself.

His actions sent a chilling reminder that there exists an unequal power dynamic between the powerful and the press, and there are “boundaries” that reporters must not cross.

Nga has also set a poor example for journalists in the field, especially rookie reporters, who might now think it safer to just record statements obediently and avoid “sensitive” questions altogether.

In short, to treat this episode as something Utusan Malaysia simply “deserved” is to expose one’s own double standards when it comes to defending press freedom.

CHANG TECK PENG is an associate professor at the Faculty of Communication and Creative Industries, Tunku Abdul Rahman University of Management and Technology.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.