LETTER | In responding to the government’s announcement that the minimum wage of urban workers will be set at RM1,200 next year, the Labour Law Reform Coalition (LLRC) urges the government to standardise the minimum wage of all workers at RM1,200 regardless of the urban-rural divide.

The geographical-based minimum wage system is not suitable for the Malaysian labour market as the government estimated 77 percent of the population will live in urban areas in 2020, in comparison with 55 percent in Indonesia and 35 percent in Vietnam.

In fact, the urban-rural boundaries are not very obvious in the country. For instance, Teluk Panglima Garang and Bangi in Selangor are not entitled to the new minimum wage rate, but both are at the margins of urban areas with a high cost of living.

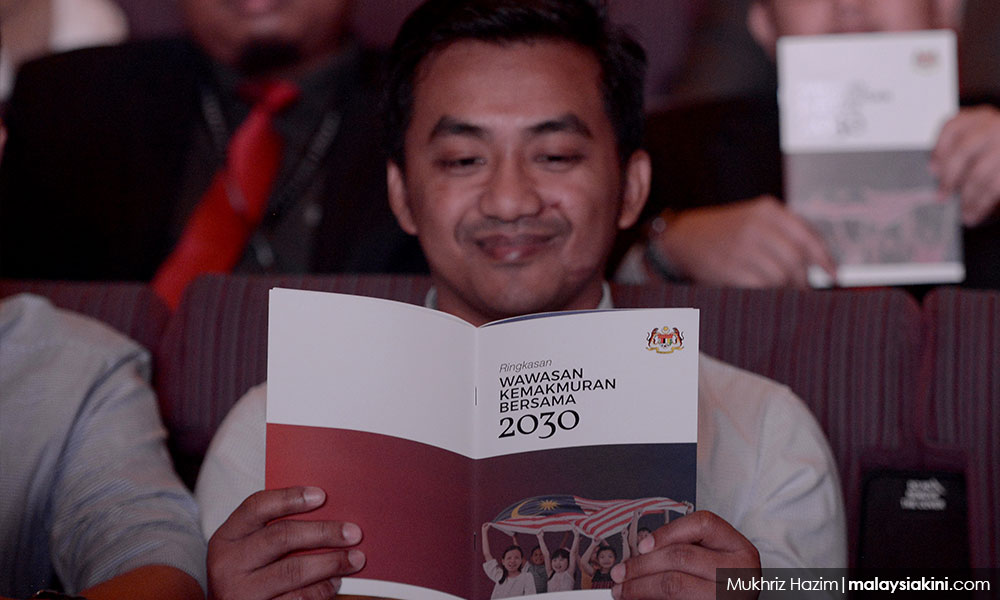

Not long ago, the government revealed its Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 (SPV 2030) with the primary aim of providing a decent standard of living to all Malaysians, one of the key indicators is to increase the compensation of employees per Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (CE) from 35.7 percent in 2018 to 48 percent by 2030.

The CE indicator is of paramount importance as it reflects that when an enterprise earns RM1, only 35.7 sen goes to employees, the remaining goes to employers and the government. In a more economically just society, employees usually get about half of the CE, for instance, German employees get 51.5 sen and UK employees get 49.4 sen.

Thus, the 48 percent target of the SPV 2030 is ambitious and doing justice for Malaysian workers. It definitely has the full support of Malaysian trade unions and worker organisations.

The key question is, what is the roadmap? We have serious concerns about how a slow-paced minimum wage increment can achieve the 48 percent CE target given that Malaysian workers are severely underpaid.

A Bank Negara (BNM) study has shown that Malaysian workers were paid only one-third in contrast with selected benchmarked economies. A Malaysian worker received only US$340 when his or her productivity is US$1,000. BNM recommended that Malaysian labour laws must be revamped to ensure Malaysian workers get a fairer share of enterprise profits.

LLRC calls on the government to devise a comprehensive plan to achieve the CE target as it requires more policy tools than a minimum wage system. The labour laws need to be further reformed to facilitate the realisation of SPV 2030 goals.

We urge the government to facilitate union recognition and a collective bargaining process by changing the secret ballot formula based on vote cast and take stern action against employers who intimidate workers in seeking recognition process.

The South Korean government has led by example in Asia by imprisoning the top management of Samsung. Our government must follow this example if it aims for a just economy.

Free collective bargaining, one of the International Labour Organisation's fundamental concepts, will help industrial workers bargain for higher wages if the industry has performed well in the year. It allows trade unions and employers to negotiate for a win-win deal with higher CE and benefits for workers.

The minimum wage should only act as a floor to ensure no workers live below unacceptable and poverty wages. Without the free collective bargaining system and realising workers’ rights such as freedom of association, it is doubtful that the minimum wage system alone can achieve the CE target.

In addition, the Ministry of Human Resources should carry out major reforms on the industrial court system in order to achieve SPV 2030 goals.

In April 2019, LLRC had proposed to the Ministry of Human Resources that the subsection 30(4) of Industrial Relations Act on industrial court awards must be amended so that the wage increment in collective agreements should only consider “the standard of living of the working family, the financial implications of the company and the industry concerned”.

We argued that the existing provision that said the industrial court awards “shall have regard to public interest, the financial implications and the effect of the award on the economy of the country, and on the industry concerned, and also to the probable effect in related or similar industries” is too broad and vague.

That allows industrial court judges to make arbitrary decisions to suppress the wage proposals put forward by the trade unions that refer to the industrial court for a dispute settlement.

Considering that the industrial court often refers to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) of Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak for wage increment in collective agreements, solely basing it on the CPI only results in no increase in real wages.

Thus, the ambiguous provision of the law and the arbitrariness of the industrial court has become one main impediment of wage increment of workers and the reason why we are a low-wage nation.

The longer it takes to amend the provision of 30(4) of the Industrial Relations Act, the bigger the obstacle the government will have in achieving the SPV 2030 goals.

We hope the cabinet will set up a special committee to deliberate these proposals and formulate a comprehensive plan to realise the CE target, these measures include improving the wage determination mechanism and amending the Industrial Relations Act.

The writers are co-chairpersons for the Labour Law Reform Coalition.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.