COMMENT One of the most disappointing developments in 2015 for many is the disintegration of Pakatan Rakyat and by extension, the prospect of having straight fights between BN and the opposition in the 14th general election (GE14).

A natural deduction from the "two-party/two-coalition system" narrative, which first emerged as early as around the 1986 general election, the logic is simple: opposition must be united or it will stand no chance to defeat the powerful BN.

That BN-Umno is now increasingly unpopular under Najib Abdul Razak is a deafening reminder of what golden opportunity is being lost.

Many have yet to give up the dream of having a united opposition front.

Some are talking about a four-party election pact for the opposition.

Others are testing the waters - of reviving Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah’s 1990 model of two parallel coalitions with a common member. Then there is the new Pakatan Harapan consisting of PKR, DAP and Parti Amanah Negara (Amanah), and a remnant Pakatan Rakyat consisting of PKR and PAS.

While the thought may be noble, the idea of having a one-on-one fight arrangement between the Opposition and BN may be simply infeasible in itself, and at the same time, insufficient and unnecessary for ousting BN.

No, this is not at all a suggestion that it will be an easy task for the currently fragmented opposition to ride on the anti-Najib wave to unseat the ruling coalition.

The battle would be much tougher in comparison to the 2013 general election, but counting on PAS to bring about the change may just be a pipe dream.

Here’s why.

Why a four-party pact is infeasible

The first prerequisite for a four-party pact to work is that it must suit PAS’ best interests. So, what will constitute the best interests of PAS as a political party? Seat allocation in the short run, longer-term competitiveness and ideological credential would be central.

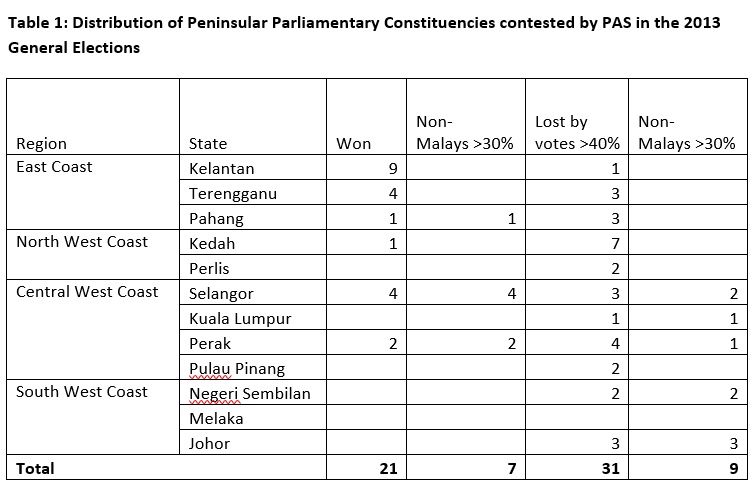

Let’s first look at seat allocation. PAS contested 65 parliamentary constituencies in West Malaysia in 2013, winning 21 of them. In 31 other constituencies, PAS lost but garnered at least 40 percent of the votes.

To make the four-party pact viable, PAS may have to give away some of these 52 won and winnable constituencies to Amanah. At the very least, Amanah will demand 16 constituencies with at least 30 percent of non-Malay voters, which PAS is sure to lose.

If PAS concedes these 16 constituencies, it will be basically left with Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang on the east coast; and Kedah, Perlis and Penang in the north.

Even if Amanah is magnanimous enough to give up all seats in the eastern and northern states, will PAS loyalists in all the west coast states south of Kedah be happy to sit out GE14, and possibly all future elections?

More important than the short-term electoral consideration would be PAS’ longer-term positioning.

Which party would pose the greatest threat to PAS in the years to come - Umno or Amanah?

Clearly the answer is not Umno. PAS is itself a splinter party of Umno and has survived Umno’s competition for six decades. When not even a strong Umno under Dr Mahathir Mohamad could eliminate PAS, a weaker Umno under Najib is no threat at all.

On the contrary, if Amanah survives healthily after GE14, it will have proven itself to be of a different league from previous PAS splinters like Berjasa and Hamim. This suggests PAS may instead be winnowed out of the game if "Islamist" voters decide to keep only one of them.

From the standpoint of ideological goal, Pakatan Harapan has made it clear that it will not support PAS’ "hudud agenda", while Umno is sending signals that cooperation is possible. Why should PAS work to topple a possible ally and instal a government that denies its aspiration?

Even if PAS chooses not to formally ally with Umno for fear of members’ backlash, it still makes better sense for PAS to go for three-cornered fights, to undermine Amanah and DAP when possible, and to play friendly matches with Umno.

Why one-on-one fight is not sufficient

Before you feel depressed over the impossibility of a working four-party pact, let’s examine the logic why one-on-one fights are seemingly better for the opposition.

There is a premise to this argument – opposition parties must be able to pool votes for each other if they agree to nominate only one candidate.

However, if supporters of opposition party A find opposition party B to be as despicable as BN, they may spoil their votes or abstain from voting instead of voting for party B.

If they find party B more despicable than BN because of programmatic or personality factors, they may even vote for BN, hence reducing the chance of an opposition victory in a three-cornered fight.

Turn the logic around. When vote pooling is not possible, three-cornered fights may increase the chance of a BN defeat when its votes are split by two opposition parties appealing to different segments of voters.

This was why in the 1982 general election, for example, PAS contested 81 out of 114 parliamentary constituencies in West Malaysia, and DAP contested 56, resulting in 32 three-cornered contests.

BN leaders rightly saw such three-cornered fights as a manifestation of PAS-DAP’s "unholy alliance", when their supporters still could not see eye to eye.

So, even if PAS is willing to enter a four-party pact, can it work?

Can PAS supporters bring themselves to support Amanah, which pursues maqasid syariah (substance) over "hudud punishment" (form), let alone DAP, which rejects outright PAS’ "hudud agenda"?

Can secular supporters of Pakatan Harapan bring themselves to support Hadi Awang, PAS and their "hudud agenda"?

Without a workable programmatic consensus on fundamental issues like "hudud agenda", even if one-on-one fight arrangement is attained, it is not sufficient to bring about opposition victory.

Why one-to-one fight is not necessary

A straight-fight arrangement is not only insufficient for opposition’s victory but also unnecessary.

Why? Because voters may resort to "strategic voting", meaning that voters will choose between the two frontrunners, and ignore all other candidates who are hopeless.

No matter how voters may like a hopeless candidate, voting for him/her will be a futile exercise. If voters care to make a difference, they will just vote strategically.

Once strategic voting is triggered, multi-cornered contests become irrelevant and "spoiler parties" will be ruthlessly punished.

However, how can voters be persuaded to vote strategically and back the most hopeful opposition candidate?

The voters must be convinced that the election outcome matters. In other words, voting in BN and voting in the opposition will make a real difference, not trading Coca-Cola with Pepsi-Cola.

Malaysian voters want both political reform and stability – at least for five years.

They want the new government to govern stably and steadily, cleaning up corruption and moving the nation forward.

For this to happen, the opposition needs a clear and binding consensus on major issues – Islamisation and the post-NEP economic policy are the first two that must be addressed.

Such consensus cannot emerge with politicians only negotiating on the contents of the manifesto, let alone on seat allocations. It necessitates open and constructive dialogue in society at large, so that such a consensus may emerge first among opposition supporters.

Granted, this is no easy work. But the opposition may be lucky enough to have two years.

Instead of skirting tough questions that may arise in forming a fragile electoral pact, the opposition should take the bull by the horns to build a lasting, governing coalition.

So, please. No more "strategic ambiguity" and crap like "we agree to disagree" to defer consensus-building for the pretence of unity.

Time to wake up from the pipe dream of one-on-one fight!

Angry Malaysians who want to see Najib ousted want an alternative government, not another electoral pact.

WONG CHIN HUAT earned his PhD on the electoral system and party system in West Malaysia from the University of Essex. He is a fellow at the Penang Institute, and a resource person for electoral reform lobby, Bersih.