SPECIAL REPORT Today, Malaysia celebrates the 53rd anniversary of the union between peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak.

The union marked not only the coming together of territories but also a commitment to build a multicultural and multi-religious future together.

In conjunction with Malaysia Day, Malaysiakini takes a look at a not-so-different kind of union as we speak to five different couples in a two-part series.

The couples, coming from different religious, cultural and territorial backgrounds, share their stories on how they came together and persevered despite the differences and challenges.

Here are their stories:

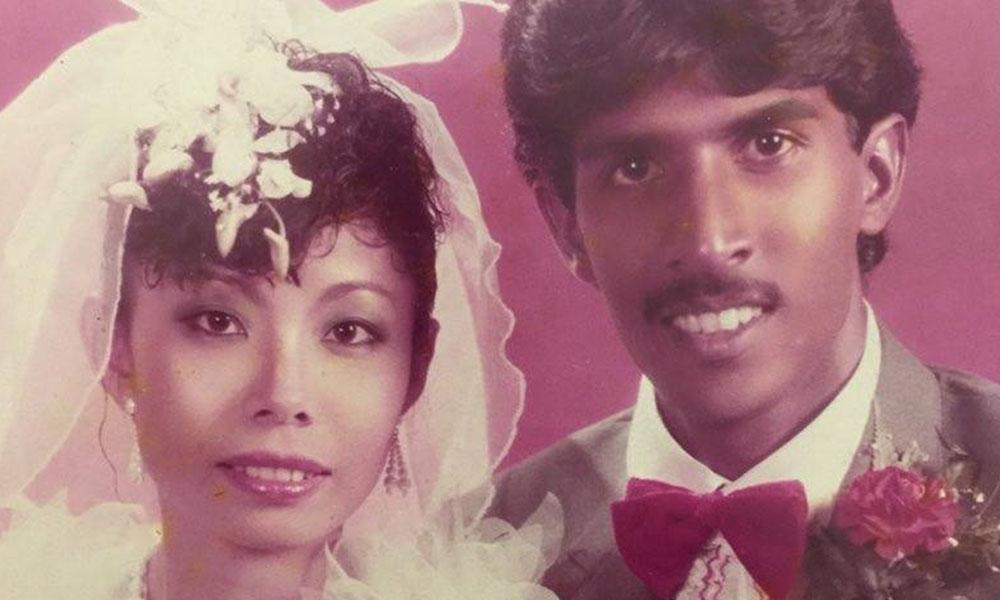

Kong Lai Mei, 55 & Cheli Tamilselvam Nadarajah, 56

Cheli and Mei met each other in the early 1980s. The romantic meet-up took place in Ipoh when both had just finished their secondary school and had moved to the city to start a new life.

Cheli first laid eyes on Mei when she visited his office to see her best friend, Mahani Osman, who was also his colleague.

The sweet, young Chinese woman made an impression on Cheli, but neither made a move until they met again in Kota Baru, Kelantan, where they enrolled in the same teacher’s college in 1982.

“I was in the teacher’s college, and she came up to me and said, ‘Hey, I am Mahani’s friend, do you remember me?’

“She said she was afraid of orientation and things like that. I asked her not to worry and that I would take care of her,” recalled Cheli.

And that was how their love story began.

One weekend in April 1983, Cheli was returning to his hometown, Cameron Highlands, to attend his elder brother’s wedding.

Throughout the entire bus ride, he felt a pang in his heart – he missed Mei.

“I bought three roses, though I didn’t know what they meant. I just wanted to get flowers for this girl. I went to college and looked for her,” he said.

“I missed her. It was strange, I told Mei. It was then when she also said the same thing.”

But Cheli soon realised his family might not approve of the relationship, and he didn't tell his parents about it immediately.

“I felt it was not quite possible to get married to this beautiful Chinese girl. I thought ‘why would this girl marry me?’” he said.

While Mei’s family was more “open-minded”, her mother did ask if there were no Chinese men in the college for her to choose from.

“I said of course there are many Chinese guys, but they are not ones I like. After that, she was alright,” she said.

Although Cheli was brought up Hindu and Mei came from a devoted Buddhist family, the couple decided to become Christians, and held their wedding in a church.

This did not go down well with Cheli’s father, and he boycotted the couple's wedding.

“It was not because Mei is Chinese, but because we chose to get married in a church. He was really opposed to that, but we were firm with the decision.

“It was not because Mei is Chinese, but because we chose to get married in a church. He was really opposed to that, but we were firm with the decision.

"We did send him an invitation but he never actually came for the wedding. It was quite hard for us,” said Cheli.

Silence grew between the newly-married couple and Cheli’s father for more than one year, but saving grace came in the form of a baby boy – Mei and Cheli’s eldest son, who melted his grandfather’s heart.

Life after marriage was not a bed of roses either – cultural differences were apparent.

“In Cantonese, there is a phrase ‘sei lo’, I think they shouldn’t have such a saying. It means ‘you are going to die’,” said Cheli.

“When the Chinese refer to Indians, they would use the word ‘keling’. From time to time I had to remind Mei not to say it,” he said, adding that Mei became more sensitive about it over time.

Cheli said he also felt out of place during their first Chinese New Year as a married couple.

“(At first) I felt I was sidelined. Mei and her sisters tried to make me feel comfortable. I felt that I was part of them then,” he said.

“(At first) I felt I was sidelined. Mei and her sisters tried to make me feel comfortable. I felt that I was part of them then,” he said.

Meanwhile, conservative traditions in Cheli’s family left Mei feeling out of sorts.

Mei had to wear a sarong when she went to her husband's family house during the holidays, as her late mother-in-law told her not to wear short trousers and short skirts under their roof.

This was because she had three brothers-in-law who weren’t married back then.

“Even at (their) home, the ladies are not supposed to sit together with men in the main hall. So the ladies have to sit in the kitchen or second hall," said Mei.

“The sisters would have to serve the brothers. The male family members would sit down and eat.

“In my family, we wait for everyone to get ready, and we sit together. That’s something different for me,” she said.

She was also not allowed to call Cheli by name in her in-law’s house, she said, but things loosened up over the years.

Now, Cheli’s hope for Malaysia Day is that the country can truly be united.

“I wish to see the Malays, Chinese, Indians, Ibans, Kadazans and everyone learning to respect one another. To have no racial politics and no racial discrimination,” he said.

“And for the government to be fair, and for us to practise meritocracy so that everyone who deserves to be given a chance should be given a chance.”

Mei longs for the country she “used to know when (she) was growing up”. Today, she said, the do’s and don’ts in interactions between different communities are growing, and barriers exist.

“There was no discrimination then, we enjoyed being with our friends and classmates regardless of race. We could go out together, and have fun and watch movies together.

“We could invite each other to our houses. It was so free. Really love those times when we could understand each other and shake hands, I really miss all that. But it is so different today,” she said.

Muhammad Zubair Sadri (Gast), 31 & Maruxa Linda Lomoljo (Lynd), 27

Filipina Maruxa Lynd moved to Malaysia at the age of seven in August 1997, when her mum was offered a job as a lecturer at UPM. But unlike other children of expatriates, Lynd was educated in a national school and speaks fluent Bahasa Malaysia.

“I am Pinoy outside, but Nasi Lemak, Kuay Teow and everything else inside,” she quipped.

A member of Beatburns, a local pop band, she and the band's drummer Gast Zubair soon fell in love and have been in a relationship since 2011.

Lynd first set eyes on Gast at an EP launching, but the drummer did not leave her with a good impression initially.

“I thought he was a very arrogant person. But after I joined a few of their jam and practice sessions, I started to look at him and the drum and thought, ‘Darn! This guy is cute!’” she said with a smile.

It was smooth sailing for the young couple until Lynd introduced Gast to her father.

“We had a fight in the car, there was a teary moment between me and my dad. Even though he likes Gast, he had this 'thing' – he was unsure what Gast was trying to do,” she said.

“We had a fight in the car, there was a teary moment between me and my dad. Even though he likes Gast, he had this 'thing' – he was unsure what Gast was trying to do,” she said.

“I said, 'look, this is what I want, and I want and need you to respect it because I am already an adult'.”

The 'thing' Lynd’s father was worried about was religious conversion. Lynd was raised Catholic while Gast is Muslim.

“In the Philippines, you can marry a Christian or a Muslim and you don’t need to change anything. That’s what worried (my parents) the most,” she said.

Gast was born and raised in a conservative family in Perak, and his parents are still apprehensive about his five-year relationship with Lynd. He has yet to officially introduce Lynd to his parents.

“My dad asked me to think thoroughly, and read more before getting married. That’s because of the difference in religion and race that he worries about,” Gast said.

But those within their musical circle are supportive of the relationship.

“In our own band, we are dating other races. We are part of a generation where a lot of us are into that,” said Lynd.

“Of course there are some who don’t know us well and hate to see us together. We can’t please everyone, right?”

Lynd believes that faith and love have no boundaries.

“Basically it doesn’t matter what race you are in, doesn’t matter your skin color, because love comes, and it sometimes stays.

“It doesn’t have to be in the form that your parents might like because it is who you love that matters most.

“If you love God, you love the person. No matter what their faith is, you should be ready to accept whatever it is. That is one of the sacrifices of interracial love relationships.”

Jacintha Tagal, 29 & Abel Cheah, 29

Jacintha and Abel met during a Valentine’s Day event nine years ago. Both were committee members of a church and someone told Abel about the new girl in college – Jacintha, from Sarawak.

“They told me she’s a Lun Bawang, I didn’t even know what it was, but that’s Jacintha’s tribe,” Abel said.

When Jacintha first arrived in Kuala Lumpur to do her A-levels, she felt awkward as many of her new friends had never even heard of the term Lun Bawang.

Jacintha's father belongs to the tribe, which has only around 50,000 people in Malaysia, while her mother is ethnic Chinese from Kuala Lumpur. Jacintha was raised in Miri and Kuching.

“One of the first few questions Abel asked me was, ‘Do you have Astro in Sarawak?’" recalled Jacintha.

"Obviously at that point I knew this guy didn’t really know any Sarawakians, and he didn’t really know where we were coming from."

Now married, Abel said he found the differences between them to be largely superficial.

Now married, Abel said he found the differences between them to be largely superficial.

“It’s what's amazing about many modern relationships today. It unites you more than divides you. Even though Jacintha comes from a very different race, we are alike in many ways.

“We have very parallel stories even though we were separated by the South China Sea. It's because of our core values and core beliefs,” said Abel.

“The best part of being in an interracial relationship is that you've got all sorts of interesting, diverse experiences, and when you are married or when you are together, two become one.

"After we got married, it was really a blending of two different cultures.”

During the first few dates, Jacintha invited Abel for a dinner with her family. As a middle-class West Malaysian ethnic Chinese man, he was expecting a family table of four or five.

“As I opened the door, an entire tribe of Lun Bawang relatives were behind the door – her uncles, nieces, nephews... it was like a festival inside a small condominium unit,” he said.

“There was a wild boar on the table, there was fresh fish. People started putting necklaces on me, asking me to try on the Lun Bawang hats. It was amazing.”

Abel was even given a Lun Bawang name.

“The Lun Bawang name sounds very Chinese, the name is ‘Ah Chang’. When the Lun Bawang name was mentioned at the wedding, people started to laugh because it sounds amazingly Chinese.

"It has a beautiful meaning though, it means ‘bright’,” he added.

The newly-weds had a good time getting to know each other and their respective cultures, but consider themselves luckier than others; their families have both been very supportive.

“Now we are married, we have to decide where we are going to spend our holidays. One Chinese New Year, we spend with Abel’s family in Penang, another one with my family in Kuching,” said Jacintha.

“Now we are married, we have to decide where we are going to spend our holidays. One Chinese New Year, we spend with Abel’s family in Penang, another one with my family in Kuching,” said Jacintha.

“It is amazing how we share festivals and experience the cultural activities together.”

Abel hopes more West Malaysians will get to know their countrymen from the east.

“We have a lot to learn from East Malaysia. I say this with a lot of sincerity.

“From a West Malaysian’s point of view, the way they live with each other, the way they do life, the way race is important but not in a way that divides them... Race and diversity are celebrated. That’s something we can learn,” he said.

“Often when we are in West Malaysia, we pay lip service to this idea of diversity but when we look around we are still sometimes fragmented.

“Certain pockets of West Malaysians do this better than the rest but we have got a long way to go. Let’s not talk about interracial marriage, let’s talk about interracial friendship. It really begins from there.”