COMMENT | On the eve of the 13th general election (GE13) in 2013, a senior member of the international press called me on the phone in Kuala Lumpur.

“How do you see things now?”

“As I see it,” I replied, “the Pakatan opposition seems to have ‘won the campaign’, as some analysts like to opine. They may well win the vote tomorrow. But the big question is whether they can win the vote-count tomorrow night—meaning, whether they can win the right number of votes in the right places and have them duly counted and credited to them.”

“Hmmmm,” was the reply.

Thirty hours later, near midnight the next day, the same journalist called me again.

“You were right!”

After we had talked a little, I was challenged.

“You sound quite relieved really,” was the pointed observation.

“Yes,” I replied. “It is one thing to win the votes. But even if the opposition wins enough of them, the question still remains.

“Will the old guard hand over the keys and levers of power in Putrajaya to them? And even if they do, can this improbable, even incoherent, coalition of popular opposition forces create a coherent government? Will they even be able to form a Cabinet? And will those appointed to it respect one another’s portfolio responsibilities and prerogatives and not encroach and intrude upon their colleagues’ carriage of their ministerial responsibilities?

“And, crucially, even if they can manage that, not everybody will be happy with the outcome. Many will be very unhappy, even righteously outraged, to see their old opposition “bogey-men and -women” assume state power. And they will want to show it, to demonstrate publicly their anger and resentment.

“So the leaders of the defeated side will not have to lift a finger themselves. Once there is an outbreak of politically-motivated civil unrest anywhere in the country, the spectre of increasing and more widespread unrest will loom.

“And nobody still in authority will be able responsibly to ignore it. So the ‘outgoing’ government will no longer be going out. Acting in concert, as they well know from long experience how to do, the political leaders, the civil service, the army and police will act to shut down all unrest and all possibilities of social confrontation and disintegration.

“They will simply set aside the results of the election, they will suspend the whole system of which national elections are a key part. They will continue to rule as before, but now on an interim ‘emergency’ basis until the situation can be defused and managed – possibly for several years.”

My journalist friend remained silent.

Not the first time

I did not have to remind a well-informed observer that the Malaysian state and permanent government know how to do this. They have done it before.

Democratic transition under electoral democracy is not easily achieved in Malaysia. The bar is set very high. Inordinately high. The bottom line here is that, while it is not easy for an opposition to win an election in Malaysia, it is far harder for them, even having done so, to assume power and rule.

For that to happen, an opposition must not only win but win decisively. Win in a compelling manner, authoritatively, so that the outgoing ruling bloc will really leave office. Because it sees that it must. That people will not have things any other way.

That, winning not just an electoral majority but a compelling moral victory, is not easily done anywhere.

And anything less than that in Malaysia, a borderline or modest opposition victory, is an invitation, if not to mayhem and chaos, then at least to democratic regression.

In 2013 the opposition, while winning a majority of the popular vote, had failed to win, on Malaysia’s very unlevel electoral playing field, that kind of not merely numerical but comprehensive moral victory in the contest for seats in the Dewan Rakyat.

The country and its people—about which and for whom, as is well known, I care greatly—had been spared some bad experiences. That is why I was relieved.

Democratic legitimacy

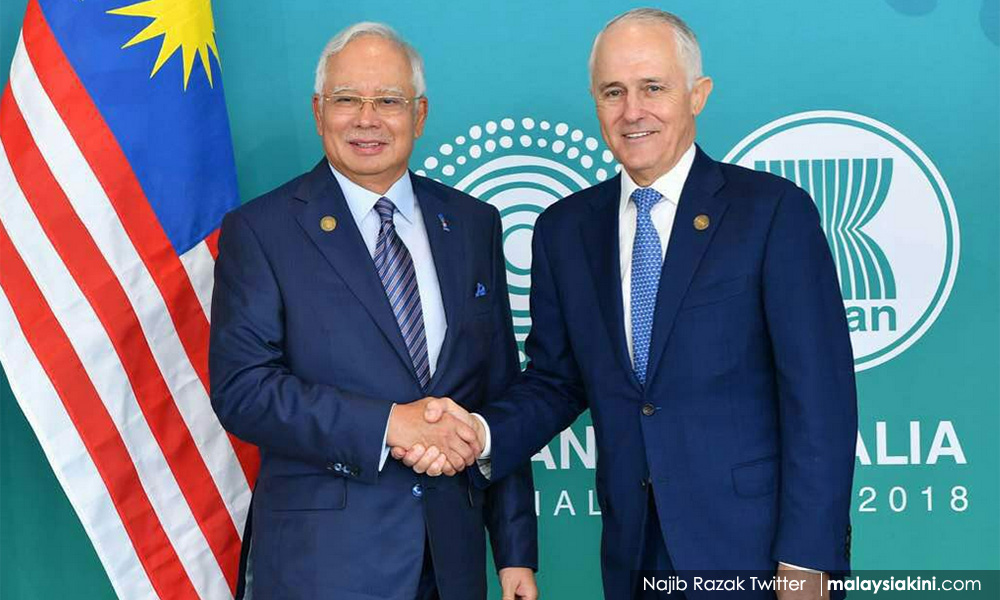

Australia and Malaysia are not two entirely different worlds.

Both countries are, each after its own fashion, constitutional monarchies.

Yet both countries are constitutional monarchies simply in technical form—in purely formal generic typology.

In real political substance and character, both are parliamentary democracies.

What this means is that the government “emerges from the majority on the floor of the house”; a majority that in principle represents the duly formed and ascertained will of the nation’s citizens as a whole.

How is the membership of “the people’s house” chosen? How, under “representative democracy”, are the people’s representatives identified?

By means of a national democratic election.

So elections are indispensable and fundamental to representative parliamentary democracy- not just because, through this device, governments emerge and are installed.

But, more basically and importantly, because it is by means of national elections that the government, the regime it heads and the entire political order at whose apex the government stands, are morally empowered, “made legitimate”.

In this way, and by no other means, our governments are given that special kind of “secular democratic sanctity” that endows modern governments and states with moral authority. A compelling authority that obliges all citizens to heed their decisions, and so makes government authoritative and effective.

For this most basic reason, election processes must be fair and clean, not distorted or manipulated exercises. If they are distorted, if they are subject to cynical manipulation, then they are exercises in “mis-representation”.

They misrepresent the popular will of the nation’s citizens by falsely selecting the people’s representatives. They and all that they deliver are, in other words, simply bogus.

When such exercises yield their maimed and misleading results, when the polls deliver “doctored” figures, it is not only the popular will that is disfigured. No less, government legitimacy, authority and all real prospects of government effectiveness are crippled and doomed. That is why governments, no less than citizens, need a good, “clean and fair” election system.

They simply “don’t have a hope” without one.

Just as sin does not give birth to virtue, so tainted and illegitimate electoral mechanisms cannot produce legitimate government.

Clean and proper elections, the very best that can be achieved in a messy and imperfect world, are necessary in any modern democracy. They are the foundation of government itself.

It is as simple as that.

‘Finessing’ the electoral system

And now? The current controversies that surround the Election Commission’s (EC) latest and quite extraordinary redelineation exercise come on top of a long earlier history of “finessing” the electoral system.

These latest “reforms” and updating, the most recent tinkering and adjustments, will only further entrench the terrible distortions that mar the nation’s electoral system. These include runaway malapportionment, the coralling and crowding of non-Malay and opposition voters within large urban constituencies (“ghetto constituencies”) – where they are seriously underrepresented—while focusing the entire electoral system upon a contest for Malay votes in far smaller, largely or semi-rural Malay constituencies, with all the ensuing ethnic and political polarisation that this strategy entails.

The Malaysian electoral system accordingly fails to correspond with or measure up to the principled criteria outlined above that are the sacred basis under modernity of legitimate and effective government.

In raw monetary terms, running an election and an electoral system “do not come cheap”. Why, one asks, is the Malaysian government prepared to invest such huge resources in a kind of election and electoral system that simply cannot deliver what governments hope and need from elections?

Why spend good money, loads of it, on a thoroughly bad product? To me that does not seem, and in the general course of things is not consistent with, “the Malaysian way”.

It is a strange but compelling question.

One that deserves some probing. And an attempt at an answer.

Cynicism, not moral authority

Here is my attempt, my probing of this very Malaysian political conundrum.

It is clear that a tainted and “rorted” system breeds only cynicism, not the moral authority to govern.

Do Umno and the EC not realise that?

Or do they simply not care?

As one has followed, with dismay, the strategic game played and the rhetorical pretexts and justifications invoked to force through the latest electoral delineation, one can reach only one conclusion.

Umno and its EC can do, and will go on doing, all that they like in order, somehow, to “win” the election, to contrive a satisfactory outcome. Meaning: to “get the numbers” where and how they are needed.

But the more they play that game of “whatever it takes”, the less can any election do what Umno/BN - like any political party anywhere - want and need from the process.

Namely democratic legitimacy.

A tainted and “rorted” system breeds only cynicism, not the moral authority to govern.

Do Umno and the EC not realise that?

They must.

Or do they simply not care?

So, now to answer my own question: No, Umno does not care. Why not?

For Umno, elections are just a formal device, a convenient and useful (if at times very bothersome and fraught) expedient.

They provide a way if not to pick then to identify and name a winner. To ensure that somebody who can be called “the winner” emerges, and can be identified, from the whole messy, artfully contrived carnival. Or, more specifically, to ensure that the winner who emerges is and will always be Umno.

For Umno, elections are just a “winner-contriving” mechanism, or gimmick, a smoke-and-mirrors show - or, to extend the county fair and carnival metaphor, a game where the blindfolded rakyat will always reliably pin the tail on the same Umno donkey - without any “moral”, legitimacy-bestowing dimension or aspect.

Umno’s source of legitimacy

For the Umno hard-men, elections have nothing much at all to do with legitimacy, the authority and right to rule.

For them - since the fashioning in 1986 of the myth that Ketuanan Melayu (Malay ascendancy) is and has always been an integral part of the 1957 Merdeka Constitution and the “social contract” underpinning it, and notably following Umno’s lurch away from the centre and back to its Malay “base” following the painful surprise of GE12 in 2008 - the ruling party’s, their own, legitimacy comes from somewhere else.

First, and in most general terms (as incisively explained by serious scholars and commentators such as Anthony Reid and Michael Vatikiotis), it is held to stand in the Southeast Asian way on archaic foundations: on a basis that goes back past the Malacca Sultanate to the pre-Islamic Hindu-Buddhist worldview and to the position within it of the Dewa Raja - the ruler whose being was embedded in the very structure of the cosmos, as the link between the sacred macrocosm and the mundane world or microcosm of struggling, swarming, earth-bound humankind. From within this worldview, the cardinal, well-known, and region-wide cultural and moral basis and principle of governance was and is still generated.

Under this venerable cultural dispensation, the mere possession itself of power entitles the holder to use it in any way that he and they can; and that it makes legitimate - meaning that it provides entitlement and justification for - anything that he, the ruler, or they, the ruling bloc, can manage to do with it. Anything that they can get away with doing, no matter how.

This is the justificatory foundation of a moral universe in which things such as the 1MDB scandal and the EC’s artful preparations for staging a periodic election-carnival are made possible and assimilated into what is offered as routine, unsurprising normality.

But this stark basis and doctrine of legitimacy is just too terrible to be openly asserted and advertised, promoted and affirmed.

That would be too shameful.

Where the ultimate or underlying basis of the ruling group’s claim to legitimacy is not one that can be publicly announced, bruited and boasted, something else must be substituted and even - against the weight of history - confected.

So in Umno’s Malay and Malaysian case, the “moral”-ideological grounding for ruling legitimacy is now provided on a different doctrinal foundation. One that is not rooted in the credibility of democratic elections and the will expressed through them of the sovereign people and nation.

Umno’s legitimacy, Umno rule, its right as its ideologues see it to go on winning elections and to take what measures, may be necessary to ensure that it always does, and Umno’s perennially proffered standing as the only conceivable “permanent government” are grounded - as those powerfully-cosseted national ideologues see and imagine and construct it - in the continuity of Malay history: as expressed, projected and asserted in ideas of enduring Malay political centrality, primacy, ascendancy, domination (“Ketuanan Melayu”) in an unbroken and politically definitive, obligatory and unquestionable line of continuity since the Malacca Sultanate.

These days, this Malay right to rule - a right closely held under exclusive Umno guardianship - is justified by the sacred political standing of Islam (under a certain revisionist understanding and rewriting of the meaning of the Constitution’s Article 3), which in turn and conversely can be maintained and assured in Malaysia only by continuing (and axiomatically unchallengeable) Malay political ascendancy; and via a continuing imperative and drive to push ever further the inherently unfinishable project of establishing and “embedding” Ketuanan Melayu.

Ketuanan Melayu, axiomatic Malay ascendancy in perpetuity, and its sacralised “tokens of warrant” or formal “letters of credential” within Islam are in turn assured and guaranteed by the Raja-raja Melayu, the Malay rulers of the old sultanate states of the peninsula, who embody and personalise and give solemn “incarnation” to the intertwined notions of the continuity of Malay political ascendancy and of the primacy of Islam as a faith, and of those Malaysians who adhere to it in national life.

A ‘purloined constitutionalism’

With all this mobilised, what else might anybody want or need?

Electorally grounded democratic legitimacy—who needs it?

Not in Umno’s Malaysia …

And yet strangely—“strangely”, since people no longer remember it, least of all many among the nation’s judges and judiciary and the politicians concerned with such matters—that idea of political legitimacy grounded in the consent of the ruled, as the stakeholders and constituent members of the nation, and as ascertained through regular democratic elections was the foundation of the Merdeka Constitution of 1957: as a modern liberal-democratic, nationally-emancipating, nation-founding and nation-shaping constitution in, and as the authenticating stamp of, an age of liberal-democratic decolonisation and nation-building.

Malaysia’s was, and still is, a constitution founded upon the core concept of the liberal-democratic age and era of progressive decolonisation: the notion and principle of popular sovereignty as the moral foundation of a nation built upon and encompassing all of its citizens alike, no matter what their different origins and histories and their varying historical pathways of entry into citizen membership in the nation.

Some lawyers make political points, and hay and careers for themselves, arguing that the words “democratic” and “secular” and “popular sovereignty” do not appear in the Federal Constitution while “Islam” and “Malay” do. They see this fact, and offer it to the courts for endorsement, as constitutionally decisive, a lay-down political winner of an argument.

They may argue, or think they can, about the meaning of black-letter words on paper, in statutes and the Constitution.

But they simply lack the historical imagination, even education, to understand that those key notions are not put as words within the Constitution precisely because they are philosophically fundamental to and assumed by it as its deepest foundations. As things that “go without saying”, things that informed people and reasonable, competent and informed citizens (including lawyers) will recognise and realise.

The efforts of these various lawyers with their impoverished sense of national and jurisprudential history and of democratic political philosophy has resulted in and bequeathed to Malaysia—as I have elsewhere called it—a “purloined constitutionalism”.

The constitutive standing of that key bundle of progressive liberal-democratic ideas - and, remember, that is why constitutions are called constitutions, because nations are constituted and formed upon them - is true not only of the Malaysian constitution. It is true of all the constitutions of the era of national emancipation through liberal decolonisation and of the nations founded up them.

Those nations, including Malaysia, and their constitutions are all children of that age and historical process, they are artefacts of and rooted in those liberal-democratic ideas.

The idea of Malaysia as a nation resting upon liberal-democratic constitutional foundations - and hence upon the necessity of regular and well-run elections to seek and ascertain and duly confirm “the will of the people” as a whole as the basic constituent members of, and collectively as stakeholders in, the nation - may perhaps sound quaint these days.

Yet if that is not still the case, why would one ever bother or need to hold elections in the first place?

Why else would Umno do it?

Even the need for appearances can be compelling.

The EC’s role

So there is just one final thing to ponder here.

Just as hypocrisy is the tribute that vice pays to virtue, so too can Umno’s Malaysia not do without this device of elections. Even coming from them, it is a tell-tale gesture towards what the Constitution is really about and what the nation and its origins really are. An acknowledgement, no matter how back-handed and tacit, of the historical reality upon whose denial Umno political dominance has come increasingly to rely and stand, especially over the last 15 years or so.

Appearances, contrived through political legerdemain, require it, they demand that elections - but only supremely manageable elections - be held.

You have to have them.

But how?

Enter here the EC.

That is their problem to resolve. For the nation and, above all, its ruling group.

The EC must run elections—and work out how to run an election—that deliver “the nation’s verdict”, even if what the nation is has to be considerably “massaged” and managed, like a tampered cricket ball, to achieve the required result.

In 19th-century France, the job was more easily done. Driven by the imperatives of elitist liberalism, they simply drew a distinction between the nation as a whole and the politically empowered so-called “legal nation” (pays légal)—by whom all the rest of the country was to be, or were deemed to be, “virtually represented”.

This would seem to be precisely what, taken to its logical conclusion and historical end-point, the doctrine of Ketuanan Melayu may one day deliver for Malaysia and Umno - and there are those who even now look towards just such an outcome. But meanwhile, what is to be done?

If you cannot yet declare that the doctrine of Ketuanan Melayu defines the identity and extent and boundaries of the Malaysian pays legal, then you have to work out some way to set aside the actual nation, exclude some parts of it, and substitute something else for the nation that in fact exists upon and through, and which underlies and gives rise to, the constitution as it is and is properly understood. This is the key question.

How is this kind of artful “substitutionism”, of replacing of the whole with the part, within “representative democracy” confected and achieved?

The time may soon come when the EC will take some advice and a lead from that which was offered by Brecht to the East German authorities after the very disappointing results, to them, of their elections in 1953:

In Brecht’s poem, an ideological functionary of the existing regime, wishing to be helpful, offers a suggestion:

Since

The people

Had forfeited the government’s confidence

and could only win it back

By redoubled effort,

Wouldn’t it

be simpler in that case

If the government

Dissolved the people and

Elected another? …

This is not quite yet what the EC is doing. But that is the logic of its actions, this is its chosen course and direction. Its immanent trajectory.

In what it does and how it operates, it has already moved some distance toward the recourse—of dissolving the existing nation and crafting a different one to take its place—that Brecht’s irony so devastatingly suggested. Brecht’s archly mischievous words capture very precisely the current role, raison d’être and modus operandi of the EC - and might very well and appositely serve as its official motto, its cogan kata and mantra.

In short: The EC is now there to contrive, produce and substitute some other, politically more convenient and amenable “voting rakyat” or “citizenry” for the one that in fact already exists on the ground - and in the nation’s post-independence history.

Like science fiction writers, the EC is in the business of imagining and then creating alternative realities – contriving absurd counterfactuals and then offering them as plausible—for people to give credence to and inhabit. People are looking forward, with all their varying views and hopes and plans and fears—to what GE14 will deliver. And to how, under the EC’s auspices, it will be delivered.

And spare a thought for them too. Their job is not getting any easier either.

CLIVE KESSLER is Emeritus Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. This article was first published in New Mandala.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.