SPECIAL REPORT | Mastupang Somoi had been a staunch BN supporter all his life.

The national coalition offered a more stable alternative compared to the fluctuating Sabah political landscape that was made up of warring local parties and shifting allegiances.

In 2010, he rejoiced when caretaker Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak announced that a commercial shrimp farm would be built in his hometown of Pitas, north Sabah.

The RM1.23 billion farm was meant to alleviate poverty by bringing industry, jobs and running water and hope for a better life.

However, four years since the farm began operations, Mastupang has become one of the chief opponents of the project.

On a recent visit to Pitas, Malaysiakini was brought on hand-rowed sampan to multiple mangrove sites along the main stem Sungai Telaga and its creeks to witness how large tracts of mangrove forests had been destroyed or were dying due to the farm.

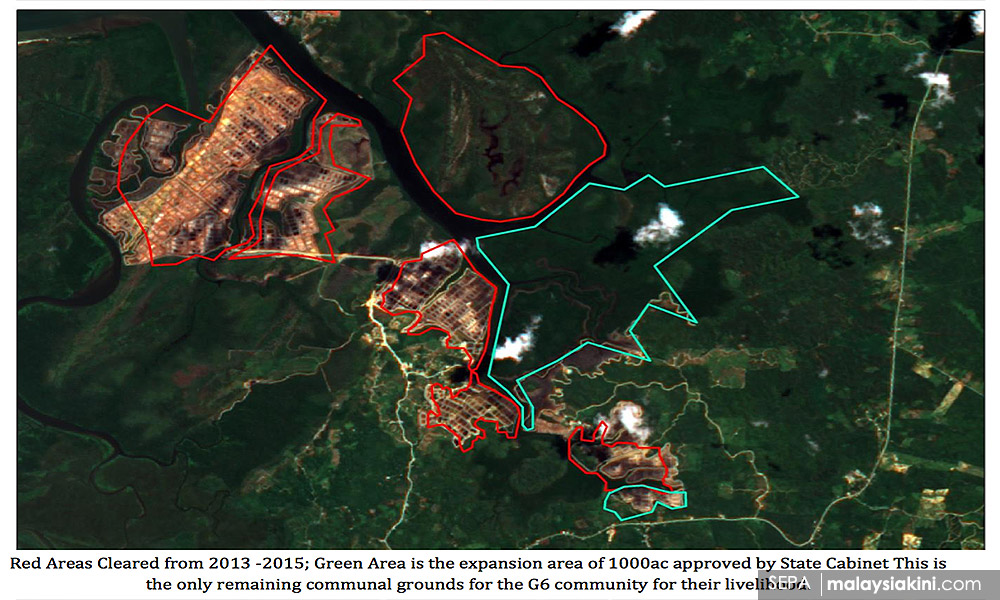

Villagers alleged that saltwater flow had intentionally been diverted while more than 2,000 acres of forest comprising thousands of mangrove trees were cleared to make way for the farm.

For generations, Mastupang and fellow villagers have foraged this very forest for fish, crabs and a local species of clam called lokan. However, this has become increasingly difficult in recent years.

“When the mangrove trees were cut down, our source of income - fish, shrimp and crabs - were all gone. When you have six kampungs foraging for food in the same area, it is even harder to find anything.

“In the past, one person would be able to fetch 200 kilogrammes of lokan each time, but now we don’t even catch enough to eat.

“Now, when we want to eat lokan, we have to buy it using money. We used to be able catch it for free and sell it to earn a small living,” Mastupang said.

The mangrove forest is also home to many sacred sites of the Tembuono, the tribe he belongs to. Some of these have since been destroyed.

Meanwhile, the 3,000 jobs promised to them by the shrimp farm have not materialised.

Mastupang estimated that at most, 30 people from his village of Kampung Sungai Eloi worked at the farm. He was unsure how many from other surrounding villagers were employed there.

Frustrated with the loss in livelihood and prospects, his son Martin was one of the many youths who left the village to look for work in cities like Kuala Lumpur.

No running water

Another unfulfilled promise was that of running water.

Back at the village, Mastupang’s younger sister Olon (photo) lives with her husband, five children, chickens and pet dogs in a basic two-storey wooden house.

For decades, they collect rainwater in large plastic drums for drinking, cooking, bathing and washing. For clean tap water, they have to travel 30 minutes to the Pitas town.

“Two years ago, someone from the farm said we would have running water but till now nothing has been done to connect the pipes to our village.

“The rain water is our only source of water. If there is a drought then we are forced to buy water from the state water department,” she told Malaysiakini when interviewed at her home.

Village strikes back

Mastupang first began protesting against the shrimp farm back in 2013, when the shrimp farm moved in and cleared hundreds of acres of mangrove forest without prior approval from the Environment Protection Department.

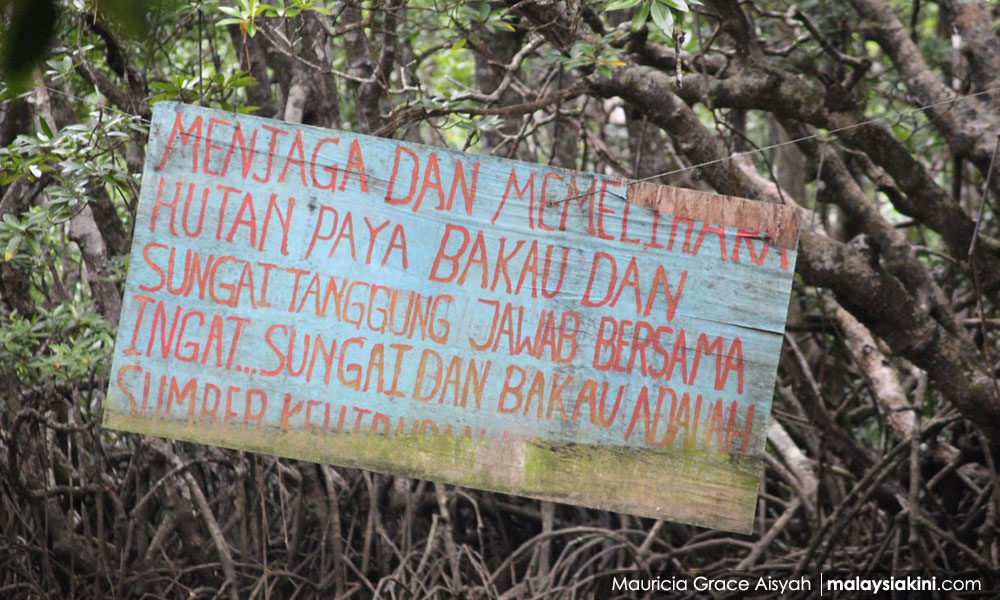

With a handful of his family members, including Olon, they put up sign boards along the riverbank to affirm that the area belonged to the community.

While they struggled to garner wider support at first, people from five surrounding villages later joined their movement after they realised their environment and livelihoods were at stake.

The farm was eventually issued two stop work orders and fined RM30,000, but the damage was done. They could no longer forage for food there and the area became an eyesore. Villagers mourned but slowly began replanting initiatives. Today, saplings grow amidst a barren land.

Assisted by the Sabah Environmental Protection Association (Sepa), the six villages formed a permanent coalition called the G6 and continued to mobilise against the farm.

When the farm sent seven excavators to clear more mangrove trees in 2015, G6 members formed a human blockade barring the machines from entering the forest. The excavators turned back.

Over the years, they have built a community centre inside the forest where they run environmental awareness programmes. They have also constructed simple huts along the riverbank for villagers to rest as they patrol the waters.

However, much to their dismay, in 2016, the Sabah legislative assembly approved yet another 1,000 acres of mangrove forest to be developed into more shrimp farms, this time by the Sabah Economic Development and Investment Authority (Sedia).

Mastupang (photo) said that these 1,000 acres are what is left of the villagers’ communal grounds for them to forage for food.

He and his group vow to protest the Sedia project will all their might.

“We have a saying - Kalau takut, jangan berani-berani; kalau berani, jangan takut-takut (if you are afraid don’t be brave, and if you are brave don’t be afraid).

“We are fighting for our future generations, for our grandchildren.

“The most important thing is our community becomes deeply aware that we can’t live for ourselves, we need to take care of everyone,” he said adamantly.

The villages presently work together to maintain constant watch over these last 1,000 acres of forest and previously held press conferences on their plight.

‘Temporary’ loss, says farm

The operator of the shrimp farm is Sunlight Inno Seafood Sdn Bhd, a joint venture between frozen seafood manufacturer Sunlight Seafood and Inno Resource Development Sdn Bhd, a subsidiary Yayasan Sabah owned by the Sabah state government.

Sunlight Inno previously claimed that it employs more than a hundred locals, and denied it had any responsibility in providing water for surrounding communities.

It also refuted that it had acted unlawfully in clearing mangrove trees, arguing that the farm is located in an area that had been first gazetted for fishery activities in 1983.

“I’m positive that any temporary loss of livelihood will be offset by the economic benefits that will eventually set in for the villagers of Pitas once our factory is fully operational,” its chief executive officer Cedric Wong told The Malay Mail Online previously.

The farm aims to be fully operational this year.

Sunlight Inno declined comment for this report.

Naysayers labelled ‘opposition’

Meanwhile, two-term Pitas assemblyperson Bolkiah Ismail refuted claims made by the villagers and characterised Mastupang’s group as a minority group aligned with the “opposition”.

Bolkiah, who was instrumental in getting the project off the ground in his capacity as Sabah’s Assistant Industrial Development Minister, contended that the project made more than RM100 million a year for Yayasan Sabah, which in turn disbursed scholarships, business grants and welfare projects to Sabahans.

“Most people are happy with the project… those opposing the project are from the opposition,” the Umno politician told Malaysiakini when contacted.

Also, while the project required mangrove trees be cut down, it was for the betterment of the people, he said.

“We did not destroy the whole mangrove forest, only 3,000 acres.

“Rather than keeping the trees, we have helped create employment. The returns are worth it,” Bolkiah said, who is seeking a third term and will be defending his seat against five opponents.

Pitas is one of three state constituencies under the Kudat parliamentary ward, which was created in 2004. BN has won Kudat with a handsome majority in each elections since.

Contrary to what Bolkiah claimed, Mastupang said the experience of his village and those in the vicinity are proving otherwise.

“In the past, no one would stop us from going into the forest. Now, as a community, we have lost everything.

“I am so sad because our lives not improved due to the shrimp farm. We have instead become poorer.

“We have lost everything,” he said while looking at his rough hands, overcome with emotion.

Malaysiakini’s reportage in Pitas, Sabah was supported by Jaringan Orang Asal Se-Malaysia (Joas).