COMMENT | ‘The rise of the Erdoğans’, a notion peddled by the international press to suggest the emergence of moderate Muslim progressives who believe in democracy, is not just a slogan.

Over the years, with or without Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as a global symbol and icon, Malaysia has seen its fair share of ‘Erdoğans’.

Be they Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Muhyiddin Yassin or the late Fadzil Noor, all Malay-Muslim parties in Malaysia have produced their fair share of forward-looking leaders.

Be that as it may, the presidential victory of Erdoğan in Turkey ought to be given due significance. There are four key reasons.

First of all, Erdoğan has been in power for well over fifteen years. While this is arguably long, it is not wrong.

Especially when the tenure had time and again been legitimised by elections in Turkey. Thus, some have unfairly accused Erdoğan of overstaying his welcome. Yet, the facts showed that the people continue to want him.

In yesterday's presidential election Erdoğan rode to victory with 52.5 percent of the popular vote. Had this dipped below 49.9 percent, he would have had to face a second round run-off.

His closest rival, CHP’s Muharrem İnce barely crossed the 30.7 percent threshold despite heavy support of the Western media. İnce also lost in his hometown, while President Erdoğan regained his support base in Istanbul.

Secondly, Erdoğan did not achieve the victory – as most if not all Islamists tend to want – by going it alone. Unlike President Mohamed Morsi from the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Erdoğan knew the importance of forming a strong and consistent alliance with nationalists.

This was how the strategic partnership between his AK Party and the nationalist MHP emerged in 2015. They each reconciled their differences, in order to find the middle ground. When they did, they held on to it.

Thirdly, while AK won 293 seats in the parliament, and MHP 49, their share of the votes from the people was at a respectable 53.6 percent.

In contrast, the opposition only had 34.1 per cent of the popular vote in the parliamentary contest, winning a total of 191 seats in all.

The Kurdish HDP party in particular gained more than 11 percent of the votes in their quest for parliamentary power.

Anti-colonial streak

Finally, Erdoğan, not unlike Mahathir, is an anti-colonialist.

While the latter is older by some 30 years, Erdoğan grew up in Turkey distrustful of what the West was trying to do to the country.

Not satisfied with denying Turkey its rightful membership in EU, Erdoğan has begun to understand the importance of East Asia.

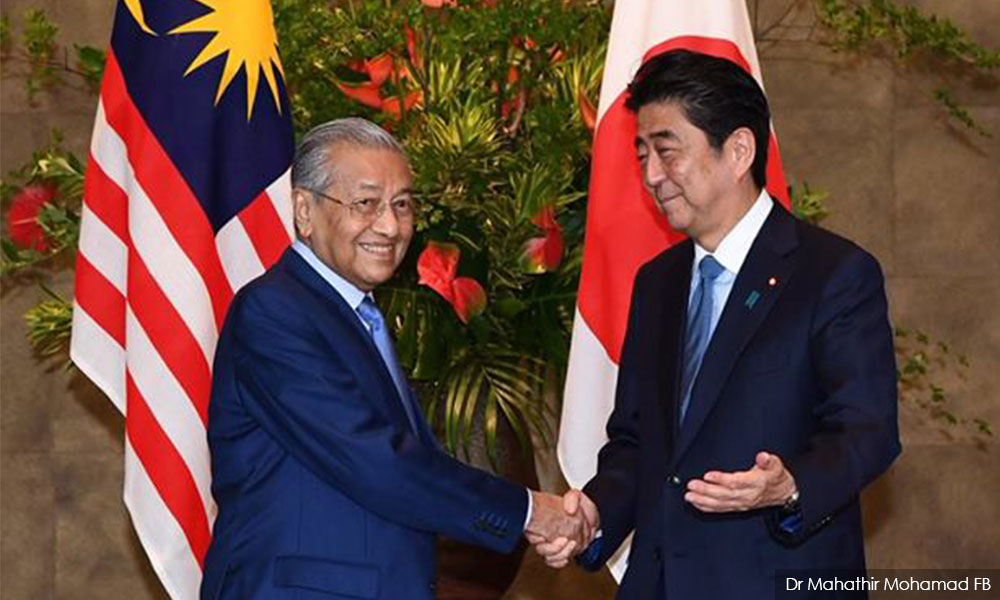

Our local ‘Erdoğans’ in Malaysia have the same predilection. Mahathir, for example, is famous for his Look East Policy, which will be updated and brought back in his current term.

Anwar Ibrahim, meanwhile, has written a whole book entitled The Asian Renaissance, where he spoke extensively of the compatibility of Islam and democracy.

The concept of fastabiqul khairat mentioned by Nik Omar Nik Abdul Aziz, or the common quest for good without any reference to one's religious background and credentials, is also a new breakthrough in terms of finding the convergence between Islam and other faiths.

There are many others in Bersatu that espouse such views too, though given the economic handicap of the Malays since the days of the colonial economy, it helps to help them first lest the country is ridden with ethnic and economic tensions.

PAS, however, seems distrustful of its ‘Erdoğans’, leading to the creation of Amanah party now led by Mohamad Sabu.

Amanah absorbed all the progressive Muslim intellectuals who had been disenfranchised by PAS, transforming each and every one of them into major figures in their own right.

If Turkey continues to thrive under Erdoğan to reach its goal of becoming a top six economy in the world, Malaysia would have to work closely with them, as without this the benefits of Europe and Asia cannot truly manifest.

Allowing the two relationships to prosper requires the existence of a Turkey-Malaysia group of eminent persons who are willing to act as sherpas guiding the leaders of both countries to the summit of international diplomacy.

RAIS HUSSIN is a supreme council member of Bersatu and heads its policy and strategy bureau.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.