In its fourth successful win of a non-permanent member seat in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) beginning next year, Indonesia has high potential to bridge the world community through consensus in finding a solution to the South China Sea dispute.

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia's director and Professor in Political Science, Rashila Ramli, said the process of "de-securitisation” must be ideally proposed by Indonesia to enhance efforts in bringing all actors and claimants', specifically China, for a better peace paradigm.

“If we really study the history of the South China Sea, it was never a security issue until 1948 when China claimed, by far, the largest portion of the territory - an area defined by the "Nine-Dash Line".

"The sea is generally a common ground used by our forefathers, more for economic activities. Looking from this particular view, the sea should be something that is protected by all of us, developed together and not something which we can own,” she told Bernama in an exclusive interview, recently.

Rashila further explained that as the security aspect was alarming, Indonesia needed to push the "de-securitisation" process at the global stage in order to escalate the discourse on peace and cooperation among UNSC members.

“Understanding the dynamics of South China Sea from the perspective of history and development, and not as a security issue aspect, it is hoped ‘de-securitisation’ will be highlighted in securing peace and stability in the maritime area.

“In this regard, Indonesia can make full use of its opportunity at the UNSC to advance the long-term understanding that the sea is more than just a sovereignty issue. Somebody (Indonesia) has to be pushing this, seriously,” she said.

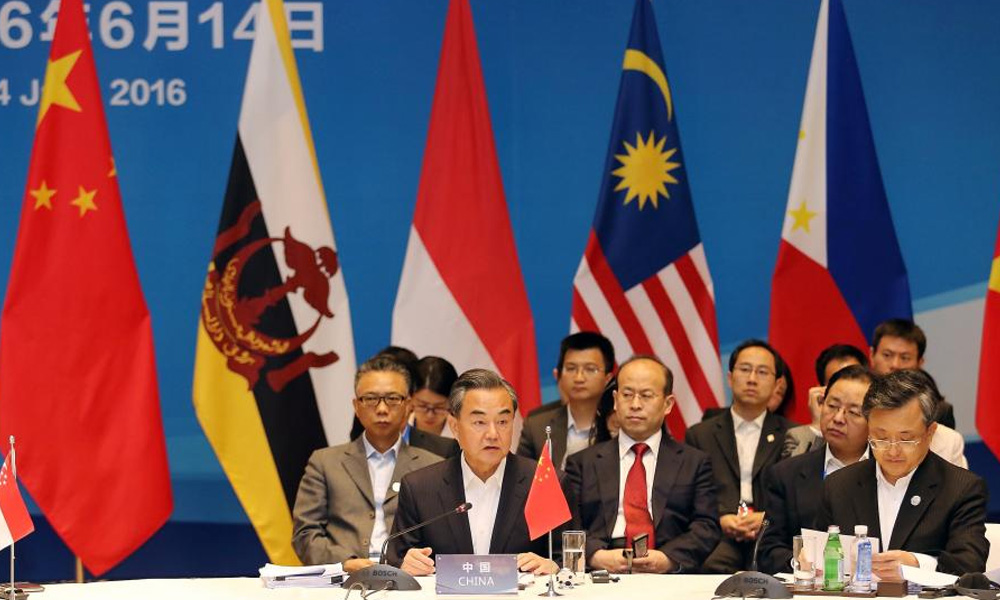

Beijing claims 'historical maritime rights'

In 1948, Beijing used the controversial "Nine-Dash Line" to claim more than 90 percent of the energy-rich South China Sea, which runs as far as 2,000km from the Chinese mainland to within a few hundred kilometres of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam.

Beijing maintains it owns any land or feature contained within the line, which confers vaguely defined “historical maritime rights”.

On the same note, Rashila opined Indonesia could maximise the neutral position role in bringing all claimants, including China, one of the permanent members in the council, to sit for a roundtable discussion.

She said the voice by Indonesia representing the Asia Pacific had the same weight or maybe more, in dealing with the issue.

“In fact, Indonesia’s position (representing the Asia Pacific) as the non-permanent member gives the country a better and stronger platform for a discussion with China.

“In negotiations, there are certain ‘languages’ and ‘vocabularies’ that can be used and from my own experiences, Indonesia can capitalise on its engagement with China by taking up more moderate, neutral positions,” she said.

Rashila added that Indonesia could also spearhead an informal consultation mechanism for security issues in the region among Japan, India and Australia that would serve as the blueprint for Asia’s stability and prosperity.

Elaborating, she said the urge to promote peace in the South China Sea was aligned with the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which highlighted ‘Peace and Justice Strong Institutions’ through its Goal 16.

“In relation to security, the sustainable development has two points of view which it can be both seen as promoting peace and creator of conflict.

“What Indonesia can do here is to try to go more for the peace and at the same time, make the world understand that a conflict can exist and can be minimised. In short, if a stronger link can be made between SDGs and security through the council, this matter (South China Sea) would be something worth fighting for,” she said.

Rashila noted that Indonesia’s strong foreign policy supported most of SDG pillars, especially global peace and climate change, and the country’s diplomats were capable of delivering their jobs.

Adopted in 2015, a collection of 17 global goals with 169 targets promoted by the United Nations, SDGs cover universal areas which include global peace, climate change, health, poverty, economic and gender quality.

Concurring with Rashila, Universitas Gadjah Mada lecturer and researcher Fajri Matahati Muhamadin expressed confidence that Indonesia’s position in UNSC would make a significant difference in South China Sea peace settlement despite China’s sign of strong disagreement.

Fajri Matahati, 30, who is currently pursuing a doctorate degree at the Department of Islamic Law of International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) believes the country’s involvement is a good step, especially in its existing relations with Third World countries.

“Indonesia is definitely not among the strongest and definitely, not among the weakest. We are there somewhere (in the middle) and in general, this is a good potential for us to initiate peace.

“In this sense, the strongest countries will not look down too much on Indonesia and the weaker countries will not see Indonesia as too far from them. This is an absolute opportunity,” he said.

Fajri Matahati has vast experience in the international law sphere.

Not only on the South China Sea, he hoped Indonesia would take good extensive steps towards other issues, especially the plight of the Rohingyas, and the Palestine and Syrian conflicts.

- Bernama