COMMENT | This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Malayan Emergency, a 12-year war declared by the then-British colonial power against the insurgent anti-colonial forces led by the Communist Party of Malaya.

The central committee of the CPM only launched the armed struggle in December 1948, six months after the declaration of Emergency. The insurgents comprised no more than 10,000 active regulars, against which the British colonial government assembled 40,000 regular British and Commonwealth troops, 70,000 armed police personnel and 300,000 Malayan Home Guards, that included aircraft, artillery and naval support.

Surprisingly, there has been little commemoration of this anti-colonial struggle by the government or our local universities, leaving it to civil society to remind the country of this fateful turn of our peoples’ history.

The Education Ministry has stressed history as a compulsory subject in the SPM. However, the ‘official’ history in Malaysian textbooks is rather suspect. It is hoped that in ‘New Malaysia’, Malaysian historical facts can be set in perspective so that the new generation understands the class forces that were arraigned during the anti-colonial struggle, who the real anti-colonial fighters were, and how the structure of the Merdeka Agreement was in keeping with British colonial strategy.

This alternative history poses five key questions for Malaysians today:

- Who were the patriots who fought to liberate the country from the British colonial power and the Japanese fascists during World War II, and who were the pretenders?

- Which parties stood for genuine and inclusive multi-ethnicity?

- How would the nation have developed if the People’s Constitution of the AMCJA-Putera coalition had been adopted?

- What is the so-called ‘social contract’ we have today and was it the same at Independence?

- How did the pattern of communalist politics that has plagued Malaysia for so long come about?

‘Official’ history banned

The most complete record yet compiled on the Malayan Emergency was written by British academic Anthony Short. He joined Universiti Malaya in 1960 and was commissioned by the government to write the history of the communist insurrection in Malaya.

He was given full assistance by the government, including full access to confidential and secret papers. When his finished manuscript was handed over to the government in October 1968, Short had to wait three years before being told that it was not to be published.

Poor Short had been too much the rigorous and honest academic and apparently, his work couldn’t be accepted to represent the ‘official history’ of the Emergency. Nevertheless, his work The Communist Insurrection in Malaya, 1948-60 was eventually published in 1975 when he lectured at Aberdeen University.

For many years, this book was banned in Malaysia. Maybe it is time we had an official explanation of why Short’s commissioned history of the Emergency was rejected by the government.

The Malaysian government is thus partly responsible for covering up dark Emergency secrets such as the Batang Kali massacre, and the use of Agent Orange to smoke out suspected insurgents in rural areas.

Seventy years after Emergency was declared, is it not time for Malaysians to read Short’s book and for the secret documents to be declassified for the benefit of scholars and other Malaysians?

A people’s history

My Patriots and Pretenders is a people’s history of the Malayan Independence struggle, quite different from the ‘official’ version of how ‘Merdeka’ was won. My earlier May 13 was the result of my having scoured documents from the British Archives, available after their 30-year secrecy was lifted.

These official documents reveal the thinking behind British colonial strategy during the Emergency, with particular reference to postcolonial Malaya. Interestingly, they also reveal the efforts by the British High Commissioner himself in the formation of the Alliance, a fact that will surprise many.

It is now 70 years since the Emergency, so isn’t it time the country properly acknowledges the contributions of the patriotic class forces in all the ethnic communities to Independence and nation building?

The atmosphere of repression during the Emergency provided the British colonial power with an opportunity to deflect the forces of revolt and effect the neocolonial accommodation. The entire colonial strategy – especially the aftermath of the Malayan Union crisis – had convinced the British that the custodians of an Independent Malaya would be the traditional Malay elite.

This was in keeping with the communalist strategy of British rule throughout their colonisation of Malaya. At the same time, the neocolonial arrangement had to accommodate the upper strata of the non-Malay capitalist class who were a necessary link in the foreign domination of the Malayan economy. The repression during the Emergency enabled the colonial government to exploit sectional interests and thereby isolate the working class and the peasantry.

So who were the main opponents of the British colonial power, and who put up a protracted struggle to end the exploitation of the country’s natural and human resources while forging a truly multi-ethnic peoples’ united front?

The class forces at Independence

The Umno leadership after World War II represented the interests of the Malay aristocracy. They were by no means anti-colonial, and did not challenge British interests.

Malaya was still very much dependent on export commodities, largely rubber and tin. The industrial base was narrow and based on these two commodities while the problem of the peasantry since colonial times was still unresolved.

The colonial Malayan economy saw a neglected peasantry, while crucial questions of exploitation by foreign capital, land ownership and size of landholdings of the Malay peasantry (for which the Malay aristocracy was responsible) were deflected into grievances against non-Malay middlemen.

The mass-based anti-colonial movement, on the other hand, had very clear policies based on self-determination, civil liberties and equality. The workers’ movement was the main threat to colonial interests, and the Federation of Malaya proposals culminating in the Merdeka Agreement were intended to deflect the working-class revolt by introducing communalism in the Independence package.

Any history textbook has to include the history of Malayan workers’ struggles, such as documented in MR Stenson’s Industrial Conflict in Malaya: Prelude to the Communist Revolt of 1948.

The constitutional crisis and labour unrest had led to the Emergency being declared on June 17, 1948. Note that the CPM only declared war on the colonial power six months later in December 1948.

Between 1948 to 1960, thousands were deported to China, while some 500,000 were displaced into ‘New Villages’. In looking at the citizenship issue, it is worth noting that by 1947, three-fifths of Chinese and one-half of Indians in Malaya were born here, but by 1950, only 500,000 Chinese (one-fifth) and 230,000 Indians had Malayan citizenship.

Western interests and the neocolonial solution

From the Colonial Office and Foreign Office documents of the period, it has been possible to provide evidence of the thinking and calculation of Western interests with regard to Southeast Asia, but especially the importance laid on securing Malaya for economic, political and military-strategic interests.

They show the priority accorded to defeating the anti-colonial forces spearheaded by the workers. The postwar period was also one of re-dividing the world by the Western powers, which under the hegemony of the US, began to move toward an integration rather than division of interests. These records reveal the articulation of the whole Western, rather than solely British, interest in Malaya.

The Emergency was as much a crackdown on the workers’ movement as it was a war against the anti-colonial insurrection. The subsequent ‘Alliance Formula’, comprising the Malay aristocratic class and non-Malay capitalist class, was designed to deal with the workers’ revolt and put in place a neocolonial solution.

Thus, the 'Alliance Formula' with all its contradictions was devised in independent Malaya. The reform measures conceded by the colonial power and grudgingly agreed to by the Malay rulers were in many ways necessitated by the ferocity of the revolt.

The Independence struggle and the Merdeka Agreement have to be understood in class terms – the ruling class in the making represented by Umno, MCA and MIC on one side, and the truly anti-colonial forces in the AMCJA-Putera coalition representing the workers, peasantry and disenchanted middle class on the other.

Thus, the so-called ‘social contract’ would have looked very different if the People’s Constitution of the AMCJA-Putera coalition had been adopted.

The Malayan Union proposal by the British in 1946 was opposed by the political left and right in Malaya for different reasons. Basically, the postwar Labour government in Britain had to grant civil rights including citizenship for the non-Malays as in elsewhere in the postwar world, but the Malay elite were opposed to this. The latter also opposed the Malayan Union because it proposed to transfer the sultans’ jurisdiction to the British and abolish the need for royal assent to legislation.

On the other hand, the peoples’ anti-colonial forces opposed it because it did not propose self-rule and no elections were contemplated. They were also against the exclusion of Singapore from the federation.

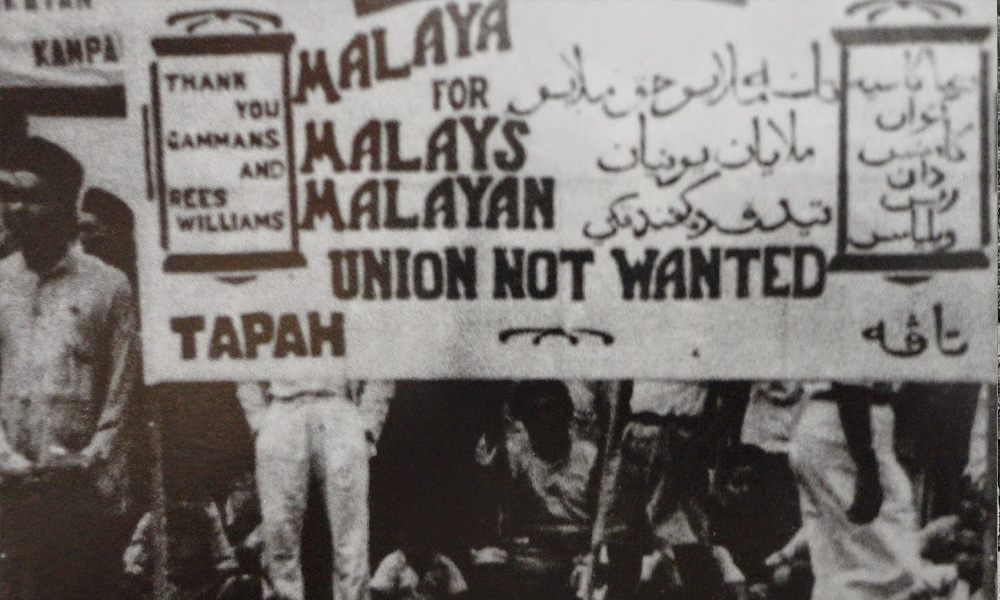

In their demonstrations against the Malayan Union, Umno carried banners calling for, among other things, denial of citizenship rights for the non-Malays but they did not oppose British colonial rule per se. Umno’s opposition to the Union had been mainly provoked by the brusque manner in which the British had forced the sultans to sign the treaties.

By contrast, Parti Kebangsaan Melayu Malaya (PKMM) called for, among other things, the right to self-determination of the Malayan people; equal rights for all ethnic communities; freedom of speech, press, meeting, religion; improving standard of living for all; improving farming conditions and abolishing land tax; improving labour conditions; education reform on democratic lines; and fostering friendly inter-ethnic relations.

On Oct 20, 1947, the AMCJA-Putera coalition launched a hartal to protest against the constitutional proposals. It brought the country to a complete standstill. It also called on all parties to boycott the Federal Legislative and State Councils.

Realising the different class forces opposing the Malayan Union, the British did a volte face and began to consult only with the Malay elite to the exclusion of all the other interest groups.

The colonial power again used its divide and rule strategy to put the anti-colonial forces on the defensive by: tightening up citizenship rules from five to fifteen years’ residence under the Federation of Malaya proposals of 1948; excluding Singapore from the federation; and removing representative democracy.

The 1952 Kuala Lumpur Municipal Council elections, which saw the successful application of the Alliance formula, gave the British colonial power an indication of the political forces to back for the neocolonial solution.

The 1955 federal legislative council elections confirmed their choice of the Alliance, and when it reneged on its amnesty proposals for the guerrillas at the Baling talks, the British were assured of the Alliance’ reliability as the custodians of their interests.

Lessons from the Emergency

According to Frantz Fanon, decolonisation is invariably violent. The Malayan Emergency was certainly a violent chapter in Malayan history, and predated the Vietnam War in its scale and intensity of repression in the region. Many lost their lives and freedoms, thousands were banished from our shores and some, such as the families who lost their loved ones in the Batang Kali massacre, are still seeking justice and closure.

Detention without trial and restrictions on workers’ organisation and activities were initiated during the Emergency repression, and detention-without-trial laws remain on our statute books today.

The labour movement has scarcely recovered since. It is high time our labour laws were reformed to be consistent with international human rights conventions and International Labour Organisation conventions.

The Malayan peoples’ independence struggle is an inspiring story of patriots who were prepared to give their lives and freedoms to rid the country of colonial exploitation and repression. Does our country have a monument erected to salute the patriots who gave their lives in the anti-colonial struggle?

Imagine what our nation would have become had the People’s Constitution been the federal constitution at Independence. This coalition encapsulated a more genuine multi-ethnic approach compared to the communal formula of the Alliance that was made up of racially-based parties and fraught with contradictions from the start.

The component parties in the Alliance (now BN) were unashamedly racial and have been dominated by Umno from the start. Even the prime minister in this ‘new Malaysia’ does not see the incongruence in heading a party with ‘pribumi’ (indigenous) in its name. How would these race-based parties justify their own existence if the country had an Equality Act or if Malaysia ratified the United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination?

The Malayan workers’ movement and radical intelligentsia in the anti-colonial coalition of AMCJA-Putera displayed strong organisation, solidarity and inter-ethnic unity, and this history is a source of inspiration and a model of genuine multi-ethnic cooperation for Malaysians today. Through this struggle, they developed an awareness of nationalism and anti-imperialism and the socialist road to egalitarian development.

The British colonial power used its communalist strategy to divide this anti-colonial movement by questioning or raising the issue of citizenship for non-Malays and reneging on the promises of civil equality for all. What would it have been like if all Malayans had been granted genuine civil liberties and political equality?

The anti-colonial movement was defeated largely because the Malay peasantry had been isolated from the movement, buffered from capitalist exploitation in the estates, factories and other urban industries. The colonial state did not hesitate to use crude racial and religious propaganda against the movement.

If Malaysia is to have a viable future and a new agenda for change involving all Malaysians, we must demand a fair, socially just, equal and democratic country that respects human rights and breaks through to a people-centred, non-racial agenda for change.

And when we do, imagine how much we will be able to celebrate the 100-year anniversary of the Malayan Emergency.

KUA KIA SOONG is adviser to Suaram, a human rights advocacy NGO.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.