COMMENT | China, if the historical accounts of Lord George Macartney (1737-1806) are to be believed, once reached a stage of opulence that never needed the world at all, including, and especially, England. To China, England was but a speck in the Far West.

Indeed, one of the most famous British attempts to expand trade with China demonstrates the miscommunication between the two nations.

As other historical recollections would have it, Lord Macartney led a mission in 1793 to the court of the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799) of China.

This emperor had reigned over perhaps the most luxurious court in all Chinese history*. He had inherited a full treasury, and his nation seemed strong and wealthy enough to reach its greatest size ever, and also to attain a splendour that out-dazzled even the best Europe could then offer.

Indeed, the research of Professor Frederick Wakeman once at Columbia University affirmed that "King George III (1738-1820) of England sent Macartney to convince the Chinese emperor to open northern port cities to British traders and to allow British ships to be repaired on Chinese territory."

To which Wakeman added: "Macartney arrived in North China in a warship with a retinue of 95, an artillery of 50 redcoats, and 600 packages of magnificent presents that required 90 wagons, 40 barrows, 200 horses and 3,000 porters to carry them to Peking."

Yet, as history had shown, the best gifts the king of England had to offer - elaborate clocks, globes, porcelain - “seemed insignificant beside the splendours of the Asian court”.

The Chinese emperor also insisted that Lord Macartney had to kowtow to him. Since Lord Macartney refused, all deals and negotiations were off. Some thirty years would pass before China lost to the British in the First Opium War in 1832, leading to a succession of territorial secession that led to the fall of Hong Kong, and subsequently of Kow Loon and the new Territories to the British, in turn inviting other colonial powers like Portugal to insist on getting Macao, and the works.

From August 17 to 21, 2018, Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamed would once again encounter a powerful China, possibly a thousand times stronger and scientifically more advanced than the imperial China described by Lord Macartney. Yet, China ought to remember three things.

First of all, Malaysia is not asking for any concessions. Of the eleven China projects that span Malaysia, which are worth a total of US$134 billion (RM550 billion), some of these projects have been found to be of questionable value, indeed, origins.

The total worth of the projects is based on the research of South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, which is incidentally owned by Chinese tycoon Jack Ma, whom Dr Mahathir will also meet again in Hangzhou on August 17.

Although many are deemed to be done under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of President Xi Jinping, some have a system of payment that does not reflect the very fairness and transparency urged by the president himself.

His anti-corruption drive in China, for example, has netted some 300,000 officials and unscrupulous businessmen to date.

Yet, within the context of the BRI in Malaysia, some projects carried the imprint of 88 percent of the payment being made while only 13 percent of the projects being completed.

Second, while Malaysia has discovered these financial oddities, Dr Mahathir has understood the complexities and protocols of China's inner sanctum.

Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng and the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) are not tagging along.

For the lack of a better word, despite being an elder statesman of Asia, Dr Mahathir has abided by the Malay concept of diplomacy - to not exploit the weaknesses of the others but to tell the truth.

Indeed, Dr Mahathir has embodied the idea that "Melayu pantang dicabar" (Malays do not like to be challenged or insulted), and "berani kerana benar" (to be bold is to be truthful). These two Malay adages have formed the twin templates of Dr Mahathir's key motivation to China.

Thirdly, when Sino-Malaysian abnormalities have grown to huge proportions, more than half of the combined national debt and liabilities of Malaysia of US$250 billion (RM1 trillion), it goes without saying that this is beyond government-to-government negotiations.

Something is seriously wrong either with BRI in Malaysia or BRI in some parts of the world, where a research at Harvard University conducted by Sam Barker, has shown a serious case of "debt" that is practically unpayable by sixteen countries and counting. Malaysia, luckily, is not one of these sixteen countries. But Malaysia does not want to be number 17.

Indeed, BRI ought to be applauded for its scale and ambition to connect some 68 countries to China, of which Malaysia is but a vital vector since it controls the Straits of Malacca and part of the South China Sea, hence, is one of the three littoral states including Singapore and Indonesia.

Against corruption, not China

To be sure, there are no cabinet ministers in Malaysia who, to date, oppose BRI in any way or form. They just want it to be more accountable and transparent to prevent any insidious corruption, the likes of which was practiced by the previous administration of Najib Razak.

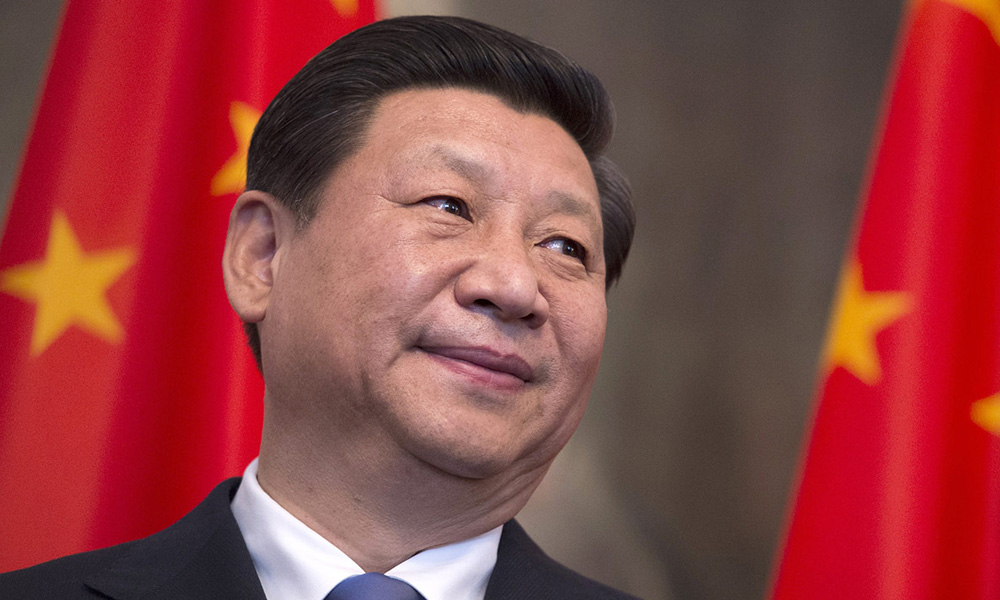

Interviews with South China Morning Post three weeks after the strategic electoral upset of May 9, 2018, also revealed Dr Mahathir's affirmation that he had once written a letter to President Xi to encourage him to build a train "1.5 times bigger (than the size of any current trains)" to pulsate the landlocked economies of Central Asia. President Xi (photo below) seemed to like the idea of reviving the Silk Road and added the "maritime portion" too, Dr Mahathir added.

For the lack of a better word, China and Malaysia do not have to allow the errors of the past administration and the unscrupulous elements in that relationship to affect the strategic partnership of the two countries.

When Japan did not want to discuss the issues of Asia in G7, it was Dr Mahathir who raised the concept of the East Asia Economic Group (EAEG), or the East Asia Economic Caucus, to former Prime Minister Li Peng in 1990, a delicate time when China was ostracised by the rest of the world due to the Tiananmen incident of 1989. Instead of ganging up on China, Malaysia encouraged China to lead Asia.

All open and classified records would show that between 1990 and 2018, Dr Mahathir had never made a single anti-China statement except when questioning some questionable deals. Dr Mahathir even dismissed the China threat peddled by some in the West and Japan.

It is with this context and backdrop in mind, that the world that makes contemporary China - whether in the physical or virtual realm - should appreciate Dr Mahathir's upcoming trip.

Malaysia does not want China to be torn asunder, like other colonial powers before had wanted. Nor does Malaysia want China to express any sympathy for its unfortunate national debt that could potentially become gangrenous.

Dr Mahathir, on behalf of many Malaysians, merely want China to listen deeply and attentively: let's aim for "shuang ying", or win-win solutions, to enrich the two countries and the regions which they represent for posterity to come.

If there are businesses and investments to be made, let the two countries and regions of Northeast and Southeast Asia merge as one grand diplomatic concert, where all can prosper in peace.

After all prosper thy neighbour is many times better than the reverse.

*The Fall of Imperial China (Frederick Wakeman, Jr, Free Press, 1977), pg 101.

RAIS HUSSIN is Bersatu supreme council member and policy and strategy bureau head.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.