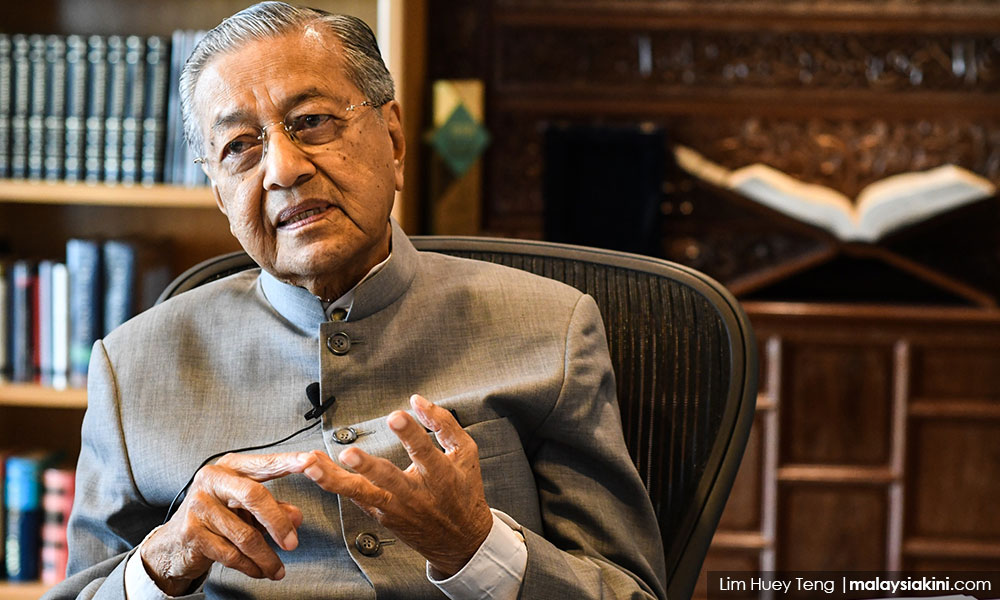

COMMENT | Dr Mahathir Mohamad touted the aspiration of becoming a high-income country by 2020 at least three decades ago when he launched Vision 2020. Beyond the catchiness of the phrase, we must question what such a goal represents for ordinary Malaysians.

Firstly, what do mean/average numbers represent in practice for people living at the bottom end of the spectrum of grossly divergent incomes, and secondly, if this is our goal, are we on track? And if we are not, what needs to be in place to ensure we are on track in moving towards such an aspiration?

A high-income economy was defined by the World Bank as a country with a GNI per capita of US$12,056 or more in 2017. Malaysia’s GNI per capita in that year stood at US$9,650. Can Malaysia become a high-income country by 2020? More importantly, can we attain that goal by increasing the national minimum wage by RM50 to RM1,050 per month as the new Pakatan Harapan government has just done?

The 11th Malaysia Plan, which covers the years 2016 to 2020, charts a path toward a high-come status by focusing on increasing productivity and encouraging more innovation as well as stressing the need for equity, inclusiveness, environmental sustainability, human capital development, and infrastructure.

In particular, it seeks to raise the living standards of the B40 to reduce the income and infrastructure gaps between richer and poorer states, and to increase the participation of women in the economy.

RM1,500 promise

During Mahathir’s previous 22-year term as prime minister, he never allowed a minimum wage law to be legislated. The national minimum wage was only legislated in 2012.

In its election manifesto, Pakatan Harapan promised to increase the monthly minimum wage to RM1,500. The current minimum wage for the private sector is RM1,000 in Peninsular Malaysia, and RM920 in East Malaysia. Unfortunately, as with the other GE14 promises, the new government has decided to increase the monthly minimum wage by only RM50 per month to RM1,050.

Will such regressive measures that can only be welcomed by backward-looking employers take us on the road to attaining high-income status any time soon?

Tough reforms with the people’s interest at heart

If we do not undertake some tough reforms that are in the overall interest of the country, starting with its peoples’ interest, this is going to be a long trip down the wrong road to god knows where.

Certainly, productivity growth is important and needs to be holistically reinvigorated for the longer term in both in the private and public sectors.

In this rapidly evolving global landscape, sustainable economic growth can only stem from a radically reshaped educational practice designed to nurture generations of innovative, competent graduates with a “growth learning mindset”, especially in technical vocational training.

What is also of concern here in workplace practices, is the dire need to foster more inclusive growth to envelop a comprehensive social protection system, especially a retrenchment and retraining scheme for displaced workers, higher participation rates of women and older people through more flexible work arrangements, and investment in early childcare and lifelong learning.

Look South for wages policy

The prime minister likes to look east for inspiration. In fact, we only need to look south, to see how Singapore achieved its high-income status in 1987. From 1979 to 1984, Singapore’s National Wages Council (NWC), a tripartite advisory body including the workers’ organisation, implemented a high-wage policy in order to facilitate restructuring to more high-tech production.

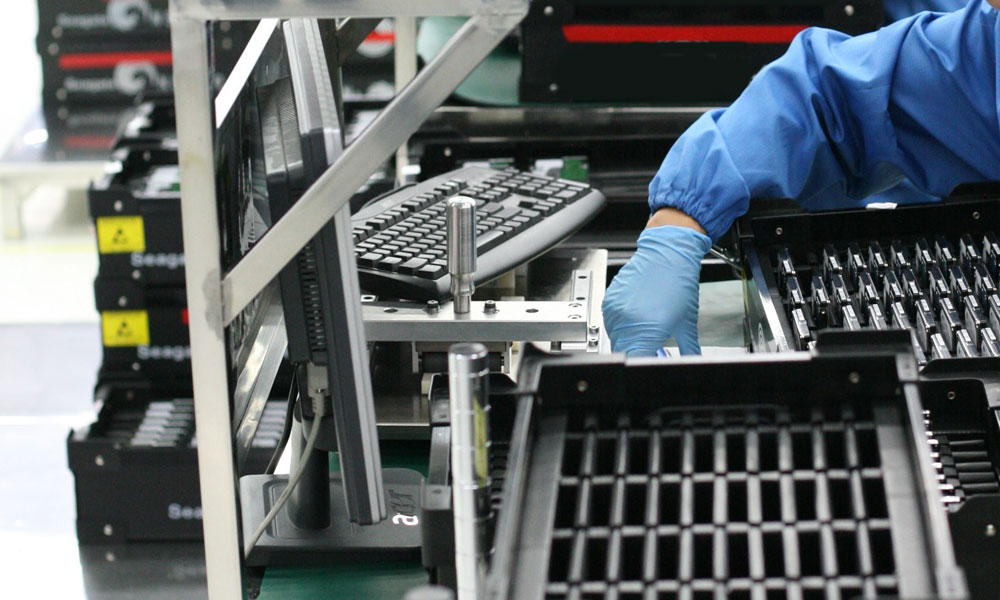

Part of this high wage was channelled into their Central Provident Fund to avoid inflationary effects. At the same time, this savings strategy was channelled into its successful public housing plan. A skills development fund was also introduced to support the shift to a higher level of mechanisation and automation. Thus, by 1985, Singapore’s labour cost had shot up to about 50 percent above that of its Asean neighbours.

The important thing was that the government did not flinch when employers protested against the wage increases. In Malaysia, ever since the minimum wage was introduced in 2013, the government would vacillate whenever employers protested against what they called higher “production costs.”

And although Singapore was similarly hit by recession during the 1984 global downturn, their NWC resorted to adjusting wages rather than downsizing or resorting to retrenchment. Thus, the high wage policy of 1979-1981 was a strategy to discourage labour-intensive production and instead for higher value-added capital-intensive production.

Malaysia, on the other hand, is addicted to years of reliance on its overflowing supply of cheap migrant labour as a consequence of which, the government has once again yielded to employers’ demands to keep the national minimum wage at the measly level of RM1,050.

There is no reason why there cannot be a sliding scale for government assistance to small and medium enterprises to meet the national minimum wage.

Workers must have a say

The National Wage Consultative Council itself had proposed a rise to RM1,250 for Peninsular Malaysia, but if the minimum wage was to be standardised it proposed RM1,170 across the country (including Sabah and Sarawak).

However, Mahathir dismissed the wages council’s recommendation. Instead, he totally accepted employers' proposal for a RM50 increase, justifying this by claiming that the national debt was way too high.

He did not explain how the national debt could be affected by the national minimum wage that private sector employers would be paying rather than the government.

As an aside, Malaysians should take note that the Finance Minister has now changed his tune about this mythical debt mountain – he now says our economic fundamentals are very strong in attempting to attract investor confidence.

Is this how workers’ representatives are treated in 'new Malaysia'? Can we allow their views in the wages council to be ignored just like that?

The Malaysian Trade Union Congress (MTUC) and several other trade unions have slammed as “humiliating” and “beggarly” the new Harapan government’s decision to increase the country's minimum wage by just RM50 a month. They are considering calling a mass workers’ protest.

The MTUC declared that Harapan had failed the poorest workers and the measure was “corporate exploitation through the government”.

As MTUC secretary-general J Solomon said: “Despite ratifying the ILO Convention 131 on minimum wage fixing, which came into force on June 7, 2017, the government has failed to take into consideration the needs of the workers and their families.

"We voted out the former government with the hope of having a government that would understand the predicament of the B40 population.”

Ignore wealth redistribution at our peril

While the prime minister may have already concluded that we will not achieve high-income status by 2020, he seems to be going down the road to perdition by selling out our workers to the short-sighted greed of backward-looking employers.

The consequences are dire for the economy, but even more so for the B40.

The increasingly serious gap in income inequality needs to be addressed through progressive taxation on the high-income earners, their wealth and property and effective tax laws to ensure there are no tax loopholes for the super-rich.

Capital allowances and tax holidays for foreign firms must be reviewed, while a tax should be imposed on all international financial transactions and hedge funds.

We need progressive taxation in order to fund a proper welfare system for Malaysians, the majority of whom do not earn enough to have a retirement, never mind the others who lose their jobs or are retrenched or are paid a measly RM1,050 a month.

KUA KIA SOONG is the adviser of Suaram.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.