COMMENT | September this year had an unusual bounty of bank holidays, and like thousands of Malaysians, I took the welcome opportunity to kick back with Billion Dollar Whale, the freshly published vita of Low Taek Jho, or Jho Low, and his role in the 1MDB scandal.

It was admittedly with some latent, lawyerly fascination with white-collar crime, on a scale which boggles the mind, that I read the book with perhaps more relish than was seemly.

The keenest pleasure of a book like Billion Dollar Whale is the exquisite knowledge that the real world comeuppance of (at least some of) its antagonists is unfolding in real time.

Providence has placed us on this side of history: the shockwaves of the 14th general election have not yet receded into our collective memory, and Billion Dollar Whale provides a voyeuristic view into the machinery of a scandal which had ignited the fury of an electorate sick of the corruption and excesses of its leaders.

A scandal that, for us looking backwards, we know would exact recompense in the national vote and reverse the fortunes of the government that enabled it.

In the wake of this seismic event, a former prime minister now stands accused before a criminal court for breach of trust and money laundering. His fall from grace was so complete, his 61-year-old coalition so utterly defeated, his mandate so unequivocally denied that it does not seem real.

In an alternate universe, the wave function might have collapsed differently. There, Schrödinger’s cat is alive, Jho Low never went to Harrow School, and he would never meet his friend Riza Aziz in London. He would not have attended Wharton Business School, and so would never meet his enduring friend and lawyer Seet Li Lin. He would never meet Youssef Otaiba, and through him, the princes of the Gulf.

There would be no PetroSaudi, no Aabar Investments, no Wynton, no Jynwel. He would never chance upon Timothy Leissner, and so could not have crossed paths with Goldman Sachs. He would know no Coutts Bank, no Falcon, no BSI Zurich. Paris Hilton would remain Jho Low’s teenage fantasy, and he would never get drunk and share secrets with Leonardo DiCaprio. Jamie Foxx wouldn’t emcee his birthday parties.

In that universe, the Terengganu Investment Authority would become a modest state fund with a royal patron, perhaps even a successful one, and it would never transform into 1MDB. In this coalescence of subatomic particles, only a billionth of a part of an atom removed from our own universe, Jho Low would never have met Najib Abdul Razak.

But he did. And it set into motion all that was to come: a series of events so profound, they would ultimately change the course of Malaysian history. Billion Dollar Whale tells that story.

The 1MDB saga – one of yachts, diamonds and Hollywood glamour purchased by the systematic plundering of a state investment vehicle, done with the connivance of politicians, princes, bankers and lawyers – makes it at once enthralling and inaccessible.

Billion Dollar Whale thus offers, from the perspective of foreign correspondents, the definitive Cliffs Notes version to what the authors present as, at its core, a Malaysian tale of greed and hubris, told against a backdrop of the failures of global capitalism. And I was seething by the last page.

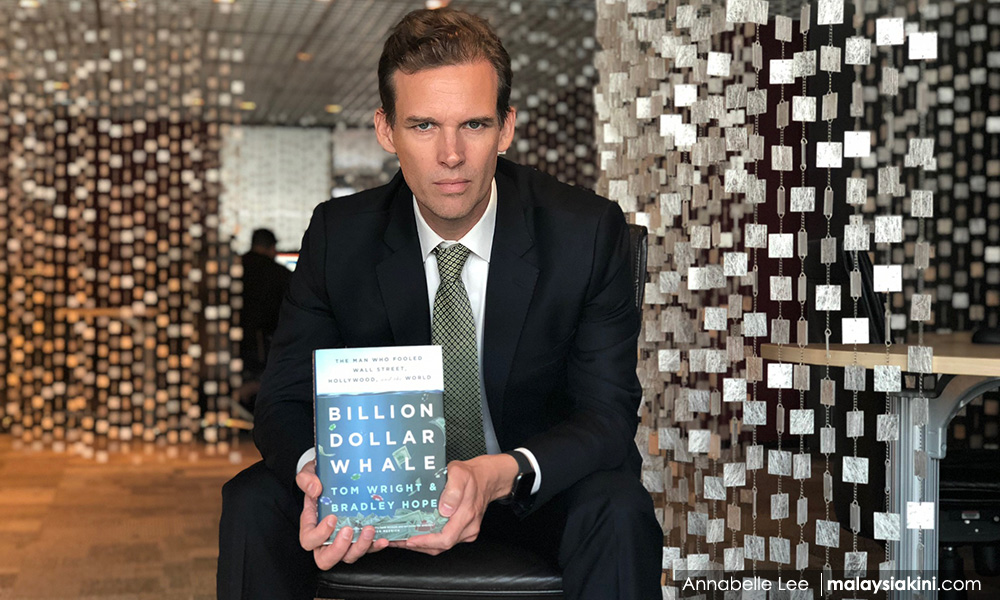

Tom Wright (photo) and Bradley Hope, the decorated Wall Street Journal correspondents who co-authored Billion Dollar Whale, rightly intuited that the book would suffer if they allowed the dense details of illicit cross-border transactions to invade the text.

Instead, they have focused on the lurid excesses of Jho Low – the titular whale – and other alleged beneficiaries of 1MDB money, while keeping the investment firm itself unobtrusively, if distantly, in view. Our attention is held by descriptions of sheer, wanton profligacy; senseless millions dissipated in an epic spending spree.

The figures are so staggering they quickly begin to lose meaning. It is nothing less than pornographic.

It was a move calculated at capturing a non-expert audience, and one that gains narrative fluency perhaps at a forgivable loss of scrupulous footnoting. Indeed, Wright and Hope’s ability to unearth a story, replete with the Aristotelian unities, from a “morass of detail” – they considered tens of thousands of documents, interviews, recollections and other sources over three years – is the book’s strongest achievement.

Wright and Hope deserve praise for an attention to detail, and the skill with which those details are woven into the story arc. The authors have demonstrated fine investigative journalism, undertaken at some cost to themselves. The book’s meticulous research, coupled with its narrative strength and the laudable economy of the writing style largely mitigate some of its more obvious sins, including some dubious stream-of-consciousness passages, superfluous musings as to the characters’ motives and the occasional lapse into pathos.

The brisk, script-like pacing and the omnipresence of celebrities is also perhaps a signal to Hollywood itself (a fact the authors have since confirmed); the exquisite irony that the Wolf of Wall Street, a film about a fraudster, was allegedly bankrolled with laundered money, would not be lost on a director like Michael Moore of Fahrenheit 9/11, or Charles Ferguson of Inside Job.

Perhaps some details were glossed over, or exaggerated to make a scene or passage more memorable. Overlapping timelines are partitioned to achieve more digestible chapters, and the sequencing of events elide a bit too conveniently. Certainly, the essentially supporting roles of superstars such as Leonardo DiCaprio, Alicia Keys and Paris Hilton appear out of proportion to how often they are name-dropped in the text.

But Billion Dollar Whale is a deliberate exposé, not an assiduous record of events. It does not pretend to be anything other than tract, but it is not essentially about greed or the failures of global capitalism. The most resonant note in the book is that of inequality.

Wright and Hope (photo) knew the incendiary effect of the shocking, unrestrained consumption the book painstakingly describes, at a time where the yawning chasm of wealth inequality has spawned such demonstrations of public fury as Occupy Wall Street.

At the same time, they acknowledge the Guccification of society where only too much is enough. We are fetishistically obsessed with the gratuitous consumption of the sort described in the book even as we denounce it frothing at the mouth. Such is the nature of wealth inequality.

Shorn of all its Marxist dialectics, its neoclassical grand theories, wealth inequality becomes as prosaic as envy. Everyone wants to be Jho Low. Everyone wants to be the 0.01 percent. Wright and Hope understand that it is not what they have that enrages us. The question that truly enrages us – what about me?

Ethics anaesthesia

There comes a point, after the story begins in medias res with a birthday party of incomprehensible extravagance – and there would be many, many parties to come in later pages – that we catch ourselves in an unguarded moment of pity for Jho Low.

The boyhood scene records a young Jho Low replacing family pictures of the owner of a yacht he borrowed to entertain his aristocratic friends from Harrow, with his own family pictures. Nerdy, uncool, well-off but not fabulously so, and embarrassed by his provincial home, he resorts to some harmless stagecraft, eager to compensate for a dozen other shortcomings.

No one is free from such youthful foibles, but we outgrow our insecurities. Jho Low’s moral relativism is suggested by Wright and Hope as the result of a lifelong sense of dislocation nursed to pathological extremes. His father Larry Low, at whose knee Jho Low learned the rudiments of offshore finance, would not only expect him to rub shoulders with the elites at Harrow and Wharton, but become one of them.

The drive to become “one of them” should be understood within the larger sense of déplacement among the Chinese Malaysian minority. Vilified for their wealth, and failing to integrate culturally, linguistically, religiously and socially with the majority Malays, Chinese Malaysians, like Jho Low, often feel estranged even in the country of their birth. Their politics are often firmly anti-establishment, the effect of generations of second-class citizenry.

Those who seek their fortunes abroad are therefore minorities within minorities, but there is a palpable sense that in the enlightened West, at least lip service is paid to the ideal that ethnicity and background do not matter. Wright and Hope acknowledge the brain drain that is slowly paralysing Malaysia’s economy, especially in the private sector, but wrongly attribute it to corruption. For many ethnic minorities, Malaysians who were educated abroad, countries such as the United States beckon because of the powerful promise of equality.

Reading between the lines, the book suggests at least one other subliminal motivation for Jho Low, one that gave him the impetus to orchestrate the heists described in the book. It wasn’t merely greed; it was the power that came with adulation, and the adulation that came with largesse. It was the kind of love you could buy; in other words, it was better than sex.

Jho Low understood that money was sexy. He understood that money meant power, and women were attracted to powerful men. The money and gifts he lavished on the playboy playmates, assorted escorts, busty croupiers and screen sirens were, in a sense, a sublimation of sex and an antidote for a crippling lack of self-esteem.

The enduring image of Jho Low seared in our collective imagination is a sweaty, cackling fat kid cavorting with Paris Hilton. Or he’s bursting out of a tuxedo plastered with a smug, porcine smile.

We cringe that our alleged criminal mastermind playboy looks so much like Kim Jong Un, even as we secretly revel that a Malaysian orchestrated a global heist, confounded global law enforcement, canoodled with celebrities and otherwise enjoyed such left-handed glory. Indeed, many may harbour a grudging respect for him. That such prestigious, glamorous deviance could be attributed to this squinty fat kid from Penang weirdly dilutes our opprobrium, and makes it somehow possible to equivocate our condemnation.

In a book where all the protagonists are villains, not everyone can be viewed in a sympathetic light, however hazy. At times, the delineation of the large cast of characters are, by Wright and Hope, perhaps necessarily, two dimensional. The Abu Dhabi and PetroSaudi cast are singularly motivated by greed, to say nothing of Rosmah Mansor. Tim Leissner’s towering ambition would prove catastrophic.

Bankers are described as, by turns, malleable and manipulative, and only too eager to accede to the whims of their rich clients for a fee. Riza Aziz comes off as petulantly entitled. Najib needed a bottomless well to buy votes; he is painted as less a tyrant than a suggestible fool, capitulating, probably against his better judgment, to the frivolities of his ridiculous wife.

Donna Tartt asks, in The Secret History, whether fatal flaws can exist outside of literature. In its own way, Billion Dollar Whale asks when the slippery slope of one dubious deal after another finally yielded to the machinations of fate.

Despite their myriad backgrounds, all of the players in Billion Dollar Whale share the same shadowy fault in their characters: a willingness to suborn their ethics, even the sacred duties of high office imposed by law, to their baser instincts. They are miscreant narcissists who truly believed they would get away with it, that history would make an exception for them.

In one of the book’s most memorable asides, Jordan Belfort, invited to the Red Granite launch party at Cannes, murmured to his then-girlfriend Anne as Kanye West rapped in the background, “Anybody who does this has stolen money. You wouldn’t spend money you worked for like that.” And he of all people would know what a powerful anaesthesia to ethics so much money can be.

Guys like us

Between Joh Low’s masterclasses in profligacy, the story of the 1MDB heists is interspersed with vignettes placing the saga within the larger story of global capitalistic failure. Chapter 16 of the book contains a handy overview of the 2007 US subprime mortgage crisis and the unconscionable profits reaped by Goldman Sachs by betting that their clients will default their loans.

Wright and Hope skirt around whether Goldman knew that the money raised by its bond sales for 1MDB would be diverted by Jho Low, but the authors certainly took pains to emphasise Goldman’s role as 1MDB’s go-to bank for what they call the Second and Third Heists (bond sales for US$3.5 billion and US$3 billion respectively) and we are thus invited to draw our own conclusions.

Goldman Sachs, behemoth Wall Street Bank and a champion for self-regulation even in the wake of Enron and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, is representative of the impunity with which global financial institutions operate. Financial institutions played a crucial role in the heists described in the book. Money was remitted through global banks into a money-laundering superhighway of funds and shell companies, travelling in a multilayered, circuitous route into private banking accounts. The control of the industry is innately flawed – the product of self-regulation and lax enforcement – and grossly susceptible to manipulation.

The industry undergoes intermittent and anaemic reform prompted by the backlash from large busts. Punishment appears to have no appreciable effect, if perpetrators are held to account at all. Ian Taylor wrote that since the Big Bang of the London Stock Exchange in 1986, the UK was “significantly opened up to a largely unregulated system for the marketing of financial securities”.

Junk bonds were already a problem since the 1980s, when investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert made US$800 million in 1986 offering bonds with high yields in order to finance takeover bids, with no financial backing behind them to give security to investors. Michael Milken, a leading Drexel executive, would end up serving jail time and paying some US$650 million in fines.

In 1998, LTCM, a hedge fund based in Connecticut, borrowed the eye-watering amount of US$900 billion, which was more than 250 times their capital, to bet on things such as interest rate futures. Their collapse threatened the entire banking system of Europe and North America. It took a consortium of governments' US$3.5 billion to bail them out. In The Gods That Failed, Larry Elliot scathingly remarked that this was one-thirtieth the amount given in emergency aid to Honduras and other Central American countries that in 1998 were devastated by deadly floods.

If Goldman Sachs appeared only too helpful to raise the money for 1MDB, and in so doing earn the hundreds of millions of dollars it allegedly received as fees, it did so because Goldman probably knew any wrongdoing this “too big to fail” bank enabled, directly or otherwise, would be difficult to detect, and there would be plausible deniability. In the face of so much profit, there was simply no incentive to play by the rules.

The compliance shortcuts and regulatory lapses occurred because key people in intermediary banks, such as BSI Singapore, were on the take, and people like Jho Low were ready to grease the wheels. Therefore, not only is there a sense of mutual gain in corruption, there is the darker sense of mutual self-destruction. There is further a sense that the money guaranteed by 1MDB, and the debt it assumed, is “government” money.

Jho Low thought, more than once, and in a supreme example of naïveté, that the government could “write off” this debt. He didn’t seem to understand that one can only write off money owed to you, not the other way round. There may also be a sense that, it being “government” money, taking it would therefore be victimless. Perhaps he thought the Malaysian taxpayer is too abstract an entity to be a victim. Until 2015, few members of the public at large even knew about 1MDB, and even once we did, none of us would have the means or standing to seek individual legal redress for the misuse of taxpayer money.

Malaysia has a robust body of anti-money laundering laws and its banks satisfy most of the international governance requirements. Bank Negara, in fact, has enjoyed international renown as a model regulator of financial institutions in the developing world. However, the problem is not a want of legislation; it is a truism that white-collar crime goes unpunished. It is doubly so when the alleged perpetrators occupy that most rarefied demi monde – the gilded world of politicians, Wall Street investment bankers and true-blood princes.

These are the people who can subvert banks, auditors, law enforcement, indeed the very organs of state to suit their means. There is one law unto them, and one for the rest of us. “Maybe it's justice,” Willy Sutton, a professional bank robber said wryly in 1974. “Defrauding the government gets them a letter from Washington asking them to come in and talk it over. Maybe it’s justice, but it’s puzzling to a guy like me.” Guys like us, Willy.

Coda

“Certain heads must fall.” As soon as he assumed the office he vacated two decades ago, Dr Mahathir Mohamad wasted no time fulfilling a key election promise: to bring the perpetrators of the 1MDB to justice, and to seek the return of assets purchased with 1 MDB money laundered through the international banking system.

In the weeks to come, all of Malaysia and much of the world would watch, flabbergasted, as hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of luxuries were carted out of houses belonging to Najib and his wife. We would watch as Riza and Rosmah are summoned for investigations. We would see, for the first time in our history, a former prime minister brought before a court of justice. We have no doubt that somewhere, Jho Low, now a fugitive, was watching too.

Billion Dollar Whale hit the shelves in the wake of the spectacular denouement, and I close this review with a note of thanks. While not a flawless work, Billion Dollar Whale is nonetheless a book apropros of its time, and an urgent injunction against hubris. Wright and Hope have written a solid and riveting account of the 1MDB story. They deserve a special recognition for their efforts in being among the first to break the story, back in 2015, and for drawing the world’s attention to this mother of all financial scandals.

Like Bill Browder’s Red Notice, this book by Wright and Hope is destined become a classic in the literature of popular economics. As I write, Jho Low is attempting to freeze the sale of Billion Dollar Whale in the United Kingdom and other places. In a statement released on his website, his representatives have denounced the book as “guilt-by-lifestyle, and trial-by-media at its worst”.

Najib's rightwing defenders will no doubt pounce on the text as a vindication of an essentially gregarious, trusting man exploited and victimised by money-grubbing minorities and foreigners. For ordinary Malaysians of every political stripe, Billion Dollar Whale will fuel discussion and debate, a seminal text memorialising the most sensational chapter in our nation’s contemporary history. We cannot forget.

BRIAN LEW is a partner in Naqiz & Partners. He leads the firm’s IPTMT practice group, and regularly advises on compliance issues.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.