COMMENT | Despite the hope for a New Malaysia, the Old Malaysia still lingers on. With it, DAP is sandwiched between an extreme Malay fringe calling for its destruction and a non-Malay electoral periphery demanding to fight fire with fire.

Pakatan Harapan has a historic mission to fulfil - proving to Malaysians that the middle ground is far more desirable than are the extreme fringes, and that the New Malaysia is mature enough and confident enough to see beyond racial cleavages and be comfortable with the nation’s cultural diversity.

This new aspiration should place its hope on Middle Malaysia - a centrist message that all Malaysians hoping for a progressive homeland can agree with. In this case, if Pakatan Harapan, DAP in particular, can overcome the many cultural challenges that it faces today, there is no reason why the country as a whole cannot become a beacon of multicultural peace and economic progress.

Since its inception in 1966, DAP has been Umno’s favourite bogeyman. The hatred towards DAP has also escalated among the Malay right-wing groups, especially since the 2008 general election.

DAP has become the scapegoat to conjure up “the Other” - be it as “Chinese”, “Chauvinist”, “Communist” or “Christian”. By framing DAP as such, Umno and its racist allies intended to strike fear into the mind of the Malays that they have no choice but to support Umno. Now with its new ally the Islamist PAS, the racial agenda is being further inflamed. According to this script, corruption in Umno is of little consequence, good governance doesn’t matter either so long as the “Malay guardian” is in power.

Many Malaysians including Malays didn’t know that ironically, in the 1960s, DAP was despised by the communists and left socialists for choosing the democratic parliamentary route instead of resorting to radical and violent actions. This is despite many political freedoms being curtailed by the then Alliance government.

Multiracial party

Right from the start, DAP had never been a single-race party. Two ethnic Malay state assemblypersons were victorious in the party’s first electoral outing in 1969. In the recent 2018 general election, DAP fielded more Malay candidates below 40 years old than Umno did. And we are here not even discussing the many distinguished Indian leaders DAP has had throughout its history, such as V David, P Patto and Karpal Singh.

There is no denying that between 1969 and 1990, the narrow political space created by Barisan Nasional resulted in DAP being unable to venture beyond non-Malay urban support base. At the same time, the rural Chinese were solidly supportive of BN.

Indeed, for a period of time, DAP was written off entirely. Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s Vision 2020 and Bangsa Malaysia, unveiled in 1991, managed to intellectually and emotionally accommodate urban non-Malay concerns such as educational opportunities, job and business prospects, and cultural space. Thus, they voted overwhelmingly for BN in the 1995, 1999 and 2004 general elections.

In 2005, after Umno had just won a very strong electoral mandate but was weakly led by Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, it decided to turn right, marked painfully by the then Umno Youth chief Hishammuddin Hussein waving the keris as a threat to non-Malays at its general assembly. Non-Malay votes began swinging to the opposition soon after, to be joined by disgruntled urban Malay voters. This gathering of anti-BN sentiments became obvious in the 2008 general election.

After 2008, DAP was ever more frequently used as the bogeyman. All sorts of issues and non-issues were headlined to paint Malay leaders in Pakatan Rakyat (and later Harapan) into a corner as “DAP stooges”. At the same time, the non-Malay press and non-Malay BN leaders in chorus dubbed DAP as “PAS stooges”, “Anwar stooges” and, of course leading up to 2018, “Mahathir stooges”.

At each turn over the past decade, I had cautioned Pakatan leaders that they should avoid falling into the trap of “siapa lebih jantan” (who is more macho). BN leaders were indeed flexing their media muscles to attract the Malay audience by painting Pakatan Malay leaders as “soft” towards DAP and “not standing up for Malay rights” while at the same time painting DAP to non-Malay audience as “soft” and “not standing up for the non-Malays”.

Common agenda

At its 2010 national conference held in Ipoh, DAP secretary-general Lim Guan Eng spoke about the need to broaden DAP’s appeal to Middle Malaysia and for the party to be identified as one that was for all Malaysians. This is what DAP is striving for together with Pakatan.

Pakatan endured because most of its leaders strongly believed that they could win across ethnic lines. They worked to develop a common agenda emphasising the wellbeing of ordinary Malaysians. Indeed, many of these leaders became politically active during or after the Reformasi— a civil movement that was decidedly non-racial.

The hate-generating machine of BTN (National Civics Bureau), special affairs department (Jasa), Utusan (print), and TV3 (TV) is now neutralised, along with the part of the Chinese media which were pro-BN. Today, the mass media as a whole is no longer muffled, although the ownership structure remains as before.

But due to more than half a decade of BN’s racial politics, many Malaysians, including the media, have yet to learn how to ask questions and to propose ideas outside the race and religion framework.

The “profiteers of mistrust” are still having a field day. We may have been free of the old hate machinery, and now able to express ourselves freely, but a confident and trusting mindset that can normalise the New Malaysia is still lacking. There is a vacuum, and the longer it exists, the more dangerous it becomes.

Herein lies DAP and Pakatan’s challenge: How to win hearts and minds across ethnic lines and across the South China Sea? How to convince citizens that the middle is more constructive than the fringes?

In short, the country needs a vision that highlights the virtues of the middle ground. Only then can we grow together and march shoulder to shoulder towards a Malaysia that is inclusive and that is an inspiration for other countries.

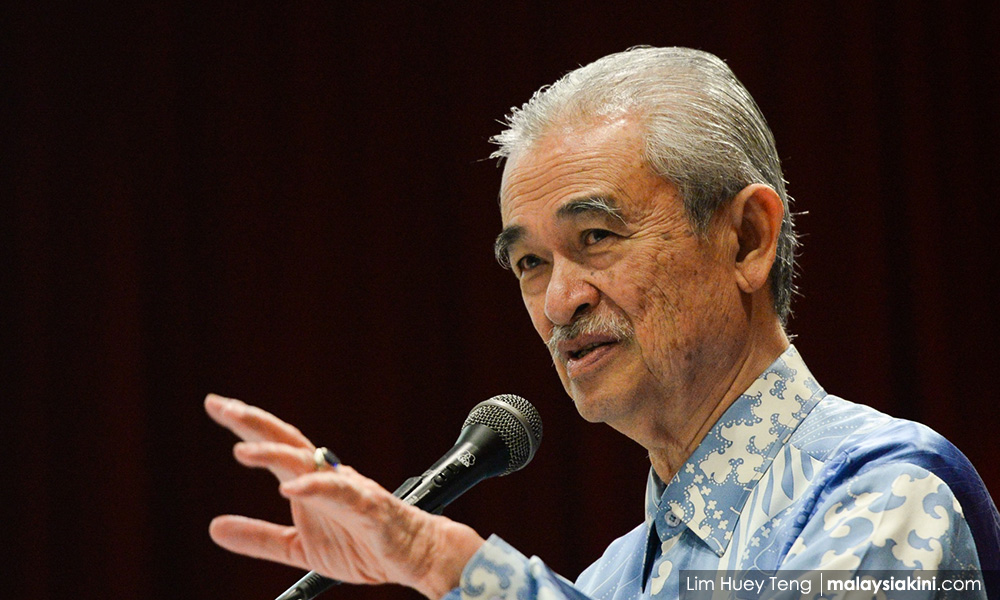

LIEW CHIN TONG is a senator and deputy defence minister.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.