COMMENT | Those with inquisitive minds wonder if, in appeal cases in the courts, there should be unanimity in the decisions. Is unanimity essential?

Unanimity, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, “is a state or quality of being unanimous; a consensus or undivided opinion.” The Cambridge English Dictionary has a similar definition.

Recent allegations have been made against former top judges of interfering with the late DAP lawmaker Karpal Singh’s criminal appeal.

What happened was that on Feb 21, 2014, the High Court found Karpal guilty of sedition in respect of comments made by him on the prerogative of rulers within the context of the 2009 Perak constitutional crisis. He was fined RM4,000.

Karpal appealed to the Court of Appeal. On Nov 10, 2014, the Court of Appeal in a 2-1 decision upheld the conviction, but reduced the fine to RM1,800.

On Feb 14 this year, Justice Hamid Sultan Abu Backer made allegations of interference with the decision of that case.

This article does not aim to argue whether or not there was interference. Instead, it wishes to shed some light on a little known feature which is of grave importance in dispensing justice.

Is unanimity in criminal judgments necessary?

Section 62(2) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (CJA) reads:

“In criminal appeals and matters the Court of Appeal shall ordinarily give only one judgment, which may be pronounced by the President or by such other member of the Court of Appeal as the President may direct: Provided that separate judgments shall be delivered if the President so determines.”

According to section 3 of the CJA, “decision” means “judgment, sentence or order”. So, reading it the other way around, “judgment” means “decision”.

Therefore, if we substitute the word “judgment” for the word “decision” in section 62(2), the section would read as follows:

“In criminal appeals and matters the Court of Appeal shall ordinarily give only one [decision], which may be pronounced by the President or by such other member of the Court of Appeal as the President may direct: Provided that separate [decision]s shall be delivered if the President so determines.”

If we take the above approach, it is clear that section 62(2) envisages that the Court of Appeal ordinarily pronounces one decision in criminal appeals. In other words, the court must be unanimous.

The exception would be where the panel of the Court of Appeal refers to the president of the Court of Appeal, who determines whether separate judgments should be delivered.

The US Supreme Court arrives at unanimity in many instances. Observers and writers suggest this is the result of comity.

At this juncture, it is worth mentioning at least two points.

Firstly, there is a like provision in respect of the Federal Court. Section 94 requires the judgment of the Federal Court in criminal appeals to be unanimous, unless the chief justice determines that separate judgments should be delivered.

Secondly, the provision requiring unanimous judgments in criminal appeals (be it the Court of Appeal or the Federal Court) is far from new.

The predecessor to the CJA is the Courts Ordinance 1948. Section 31 of the 1948 Ordinance was worded in similar terms as section 62(2) of the CJA.

When Parliament repealed the Courts Ordinance 1948 and replaced it with the CJA in 1964, it was explained that the CJA was based on existing legislation (meaning to say, the Courts Ordinance 1948). The intention was to maintain unanimity in criminal judgments as far as it is possible.

The rationale for requiring unanimity

Malaysia is not the only jurisdiction with a provision in the likes of section 62(2) of the CJA.

Singapore, England and Wales, South Australia, Fiji, and Uganda are some examples of jurisdictions with written law requiring decisions in criminal appeals to be unanimous as far as the presiding judge may determine.

In fact, in Ireland, their Courts of Justice Act 1924 does not even permit any separate judgments whatsoever in criminal appeals.

We do not have any judicial decision in Malaysia explaining the rationale for requiring unanimity. But, referring to decisions and scholarly writings from other jurisdictions, the rationale becomes apparent.

In R v Howe [1987] 1 AC 417, Lord Griffiths (at page 438) said as follows: “As a general rule, I support the view that in criminal appeals to this House it is desirable wherever possible to have one speech, so that the judges and practitioners may turn to one source for authoritative guidance. Clarity, certainty and, wherever possible, simplicity are invaluable attributes of the criminal law which must be understood by laymen.”

The courts in Singapore adopted the same rationale as can be gleaned from the decision of its Court of Appeal in Muhammad bin Kadar v Public Prosecutor [2011] 4 SLR 791 (at paragraphs 6-7).

The same is true of Uganda - see the judgment of its Supreme Court in Komakech Geoffrey & Ors v Rose Okullo (Unreported) at page seven.

Certainty and clarity aside, the other reason for requiring a single judgment appears to be premised on fairness. According to retired Australian High Court judge Michael Kirby in his 2007 Law Quarterly Review article ‘Judicial dissent - common law and civil law traditions’, he explains:

‘[I]n the English Divisional Court, dissenting opinions are not usually given in criminal appeals against conviction or sentence.

'The reasons for this tradition are obscure. Presumably it is justified by the feeling that an unsuccessful prisoner should not be upset by knowing that one judge saw merit in the appeal.

'Likewise, a successful prisoner should not be upset by any doubt cast on his or her success (and possibly an order of acquittal) by the opinion of a judge who disagreed and thought the prisoner should remain locked up.'

Technicality in the law

Among these allegations of judicial interference, one needs first to be fully aware of the nature of our criminal justice system.

The law, not just in Malaysia, but so too in many other jurisdictions, requires that appellate criminal judgments be uniform as far as possible.

This is to ensure that there is clarity and certainty in the law; and that split decisions do not adversely affect public confidence in the judiciary, i.e. that had the accused been before a different bench, the verdict might have been different.

As matters stand, the allegations that a top judge actively interfered with the Karpal verdict remain just a statement.

Proof and meat must be put on the table. And the law expressly requires members of the Court of Appeal bench to consult the president in the event of a split decision.

The public should remain abreast of this technicality in the law, rather than be easily awed or swept away by allegations of interference.

I would like to add in support of what was written in the New York Law Journal of Jan 23, 2019, that “there are several important questions a judge contemplating a dissent must deal with”.

Richard Andrais, a former New York City Criminal Court judge and an elected Supreme Court justice, warned: “If one is constantly a lone dissenter, it may be time to step back and take stock."

Editor's note: The Federal Court set aside Karpal Singh's sedition conviction on March 29, 2019.

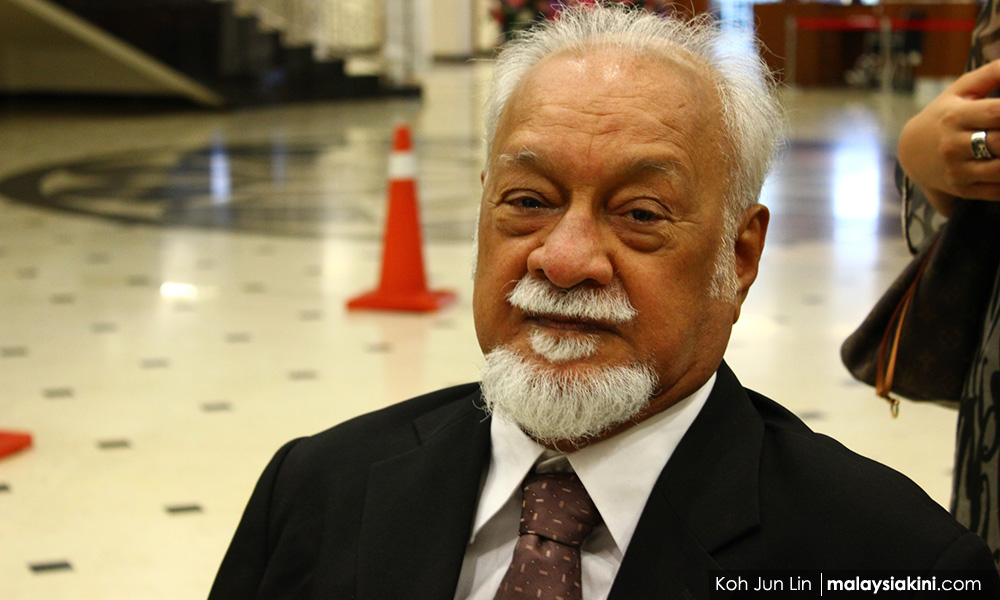

SYED AHMAD IDID is a former justice of the High Courts of Malaya and Borneo, and director of the Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration. He is also a Fellow of the Asian Institute of Chartered Bankers.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.