COMMENT | The latest deaths of 14 Orang Asli from the Bateq tribe, the country’s last indigenous nomadic community in Kuala Koh, Kelantan, with scores more hospitalised is a tragedy Malaysians should be ashamed of.

The Orang Asli are the original people of Peninsular Malaysia whose ancient ancestry in these lands qualifies them as more authentically “Bumiputera” than the “pendatangs” who came later yet claim to be exclusively Bumiputera.

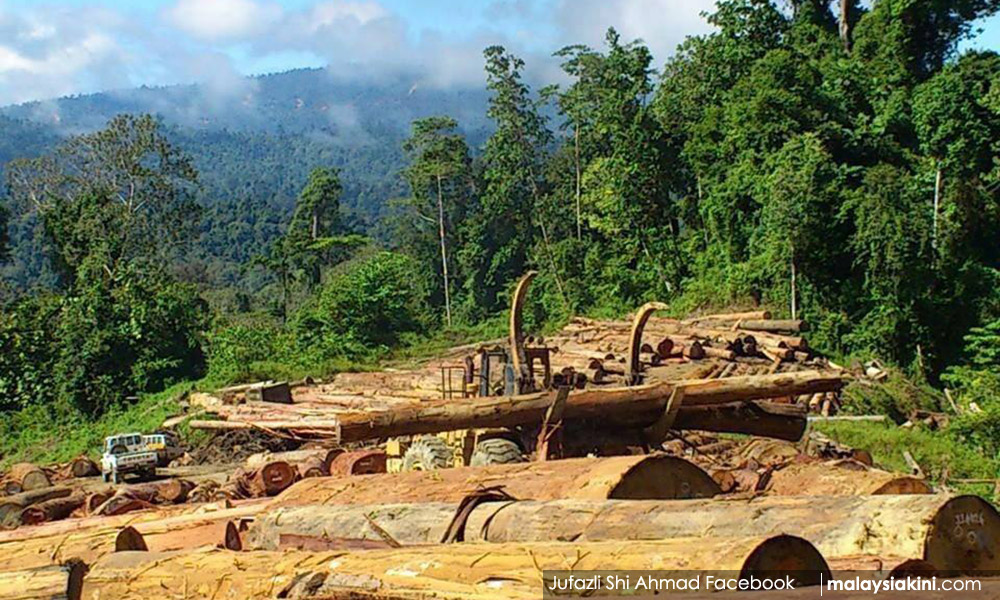

Nonetheless, ever since Independence, the Orang Asli have been increasingly marginalised and deprived of their rights to land and resources, poisoned by profits-seeking loggers, miners, plantation owners, dam builders and other so-called “developers”.

After the recent tragedy, the prime minister could only say,

“We are looking for the reason why there are so many deaths…There may be an infection of one type of disease but at this time we do not know what type of disease has caused their deaths.”

There are reported to be only 12 Bateq settlements left, living close to the Kelantan rainforest which is their ancestral home.

With poor access to healthcare, rampant deforestation of their rainforest home and pesticide poisoning of their water supply by the run off from oil palm and rubber plantations, the Bateq population has declined in recent years.

Government officials point to symptoms such as pneumonia and have alluded to “infectious diseases” despite the fact that for decades, the authorities have been made aware of the systemic causes that have led to this being a tragedy “waiting to happen”.

One would have expected the “new” government after May 9, 2018 to come out with a “New Deal” for our indigenous peoples in West and East Malaysia but the only time the Orang Asal were accorded attention was during the Cameron Highlands byelection because they make up a substantial portion of voters in that constituency.

Pakatan Harapan mooted the idea of an “Orang Asli blueprint if Pakatan won the Cameron Highlands byelection”. Whatever happened to this Orang Asli blueprint?

A “National Orang Asli Convention” was called at which the prime minister recommended enhancing education and ecotourism as a way of contributing to the economic development of the Orang Asli community.

He said the ecotourism sector would create job opportunities and encourage the youth in the community to become entrepreneurs, including making handicraft items and manufacturing forest-based products.

What was missing from the PM’s speech was the central problem all indigenous peoples face in West and East Malaysia, namely, the loss of their Native Customary Right land to logging and (oil palm and now, durian) plantation interests, as well as state governments’ so-called “development”.

Even under a PH government, there seems to be no political will to face this main obstacle to the progress of our indigenous peoples.

A doctor who knows the community has been reported to have said:

“This was a community in total neglect…Their water supply was virtually non-existent, sanitation was bad and they were suffering from all sorts of infections, showing their immune systems were very vulnerable. No effort had been made to help them.”

Moratorium on logging, mining and plantations near Orang Asli settlements

Indigenous peoples’ Native Customary Rights (NCR) lands are protected under the Land Codes of each of the states. Nevertheless, these rights are constantly violated by the government and private companies through land-grabbing or illegal encroachment.

These so-called developers continue to displace the rightful indigenous stewards of the land from their access to traditional hunting and cultivation areas and too often, from their ancestral burial grounds as in the Bakun Dam and Sungai Selangor dam projects.

This was corroborated by Suhakam in 2017 in a statement which criticised:

“…the slow progress in the undertaking of actions by the Cabinet Committee [set up by the government in 2015, for the Land Rights of Indigenous Peoples] which has resulted in continuous human rights violations of the Indigenous Peoples, especially the encroachment into their native land by developers.”

On 30 April 2017, Suhakam called for a moratorium or a temporary prohibition order to be placed on all developments involving indigenous peoples’ lands, pending the implementation of the recommendations of the 2013 ‘National Inquiry into the Land Rights of Indigenous Peoples’.

An official visit by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on cultural rights, Karima Bennoune in September 2017 unearthed further details on the human rights situation of indigenous peoples in Malaysia, including NCR issues faced by native communities in Sarawak.

Particularly revealing was acknowledgement from the Federal Government's newly empowered ‘Integrity, Governance and Human Rights Department’ that “land rights of indigenous peoples remain an unresolved human rights issue and a gap in the law which it will be studying.”

A Ministry for Indigenous Peoples

If PH is so concerned about the indigenous peoples and social justice, they should set up a ministry specially concerned with uplifting the livelihood of all the indigenous peoples in the country.

Malaysia is home to a wide diversity of indigenous peoples and all of them face life and death challenges. Their plight has often been highlighted by tragic events through the years – landslides, floods, neglect and racial discrimination.

The worst example of discrimination was shown by the admission of PH leaders during the Cameron Highlands byelection that they have just realised the desperate plight of the Orang Asli.

Perhaps the PH leaders who have suddenly become “conscientised” about the plight of the Orang Asli should prod the prime minister to lead a delegation to the Sungai Asap Resettlement Scheme to see what the prestigious Bakun dam project has done to the livelihood of these indigenous peoples from the Bakun area since 1998.

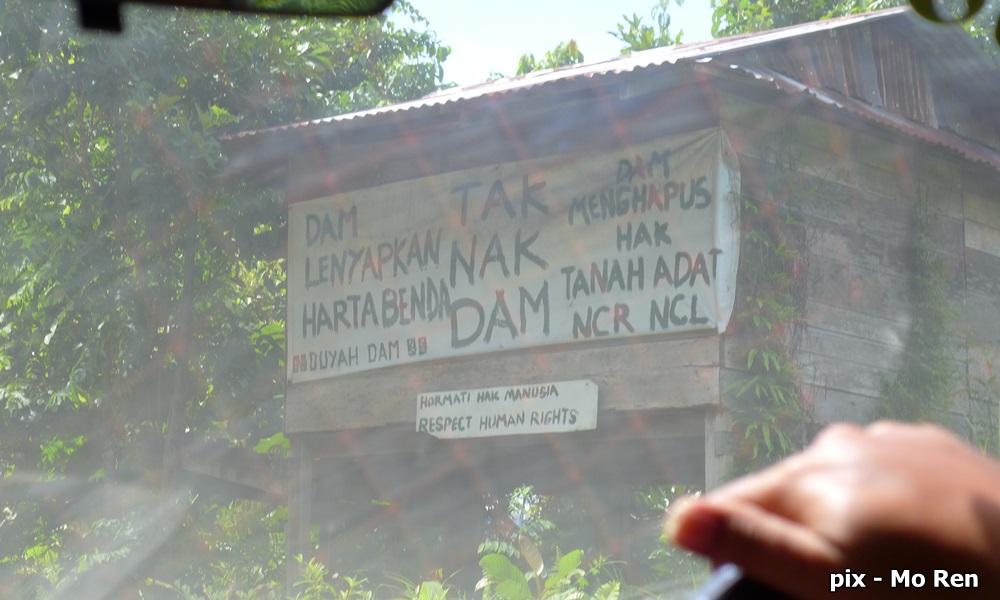

In Sarawak, the construction of Baram hydroelectric dam in Baram, Miri has been put on hold by the Sarawak Government in the run up to the Sarawak state elections.

The reason given by the late Chief Minister of Sarawak Tan Sri Adenan Satem, was that the people in Baram do not want the project. Nevertheless, the cessation of the construction work at this juncture does not necessarily mean an end to the Baram dam project as the project has been temporarily “put on hold” in the past.

Indigenous peoples who protested against the construction of the Baram Dam did so after learning the devastating stories of neglect from those communities displaced by the Batang Ai, Bakun and Murum dams (in 1985, 1998 and 2013 respectively).

Sadly in 2017, communities relocated by the Bakun and Murum dams continued to raise concerns regarding their fundamental economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) such as treated water, electricity supply, fertile farming land and access to decent roads and schools.

Apart from these notable cases that were widely publicised by the media, there have been countless other violations of human rights inflicted on the indigenous peoples of Malaysia.

Some of these violations relate to the ineffective use of funds by relevant ministries that led to poor growth and development, poor water quality that led to poisoning and in other cases, land tussles between the community and corporations supported by government.

The disastrous floods that plagued Malaysia late 2014 and early 2015 further exacerbated the human rights violations suffered by the indigenous communities, especially concerning their economic, social and cultural rights.

Swift action to improve the lives of our indigenous peoples

Suaram calls on the government to:

- Provide emergency aid to the Bateq community affected by the pollution crisis in Kuala Koh and to ensure that they are provided with clean potable water for drinking and cooking and also healthy food for the whole community;

- Bring all existing legislation dealing with Indigenous Peoples rights into accordance with international human rights standards especially the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) of which Malaysia is a signatory;

Implement recommendations from Suhakom's Strategic Framework on a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights for Malaysia in consultation with a broad range of stakeholders, including Indigenous Peoples affected by land rights issues in Sarawak;

- Ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the International Labour Organisation's Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention 1989 (commonly referred to as ILO 169) and incorporating the provisions into domestic legislation.

KUA KIA SOONG is the adviser of human rights NGO Suara Rakyat Malaysia (Suaram).

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.