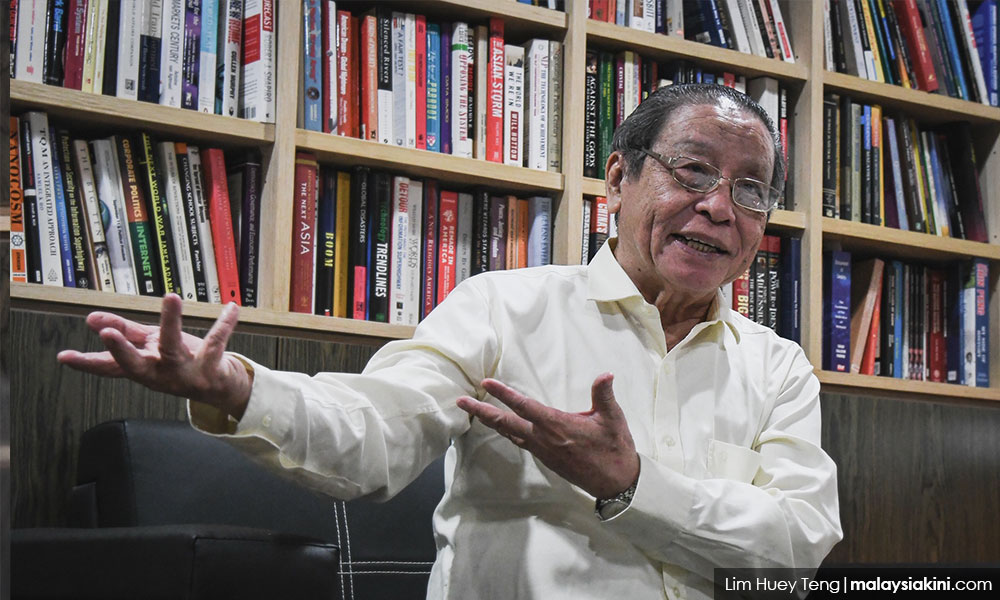

COMMENT | My association with Lim Kit Siang began more than half-a-century ago, in 1968 to be precise. He was then the organising secretary of the newly formed Democratic Action Party, (DAP).

DAP was registered as a political party on March 18, 1966, and the founding members were CV Devan Nair, Dr Chen Man Hin, Dr S Seevaretnam, DP Xavier and Zain Azahari Zainal Abidin, among others.

At that time, Devan Nair was the sole spokesperson in the Malaysian Parliament holding the DAP flag; having been elected under the People’s Action Party (PAP) ticket in 1964 when Singapore was in Malaysia. Singapore was expelled from Malaysia on Aug 9, 1965, but the Umno-led Alliance government was unhappy with his presence in Malaysian politics.

To many in the ruling party, Alliance, the presence of Devan Nair in Malaysian Parliament was an irritating relic of Lee Kuan Yew’s entry into the Malaysian political scene, which in a way introduced a brand of political thinking that involved the economic well-being of all Malaysians and mutual respect, thus moving away from race-based politics pursued by Alliance, its partners, and the extreme leftist ideology advocated by socialist parties that had found common ground in forming the Socialist Front.

The political philosophy of the Alliance was not only outdated, but had the effect of stifling the growth of multi-racial unity and importantly, religious harmony. Umno believed in unity based on race and religion and its own pattern of culture. Having built a strong Malay base, Umno thought it would be in a better position to accumulate unrivalled political power and economic empowerment of the Malays.

The philosophy of power-sharing was accepted as the most fundamental base for governance in this country, and improvement of the economic status of the Malays was acknowledged as a national programme, but that does not mean the rest should be discarded.

However, the economic empowerment of Malays did not translate into policy correctly, as the actual beneficiaries were a handful of Malays who were cronies of those in power.

The expulsion of Singapore was not received well, even in Umno quarters. There were some in that party who thought that the draconian Internal Security Act (ISA), now repealed and substituted with worse provisions, was enough to deal with Lee Kuan Yew and keep Singapore within Malaysia.

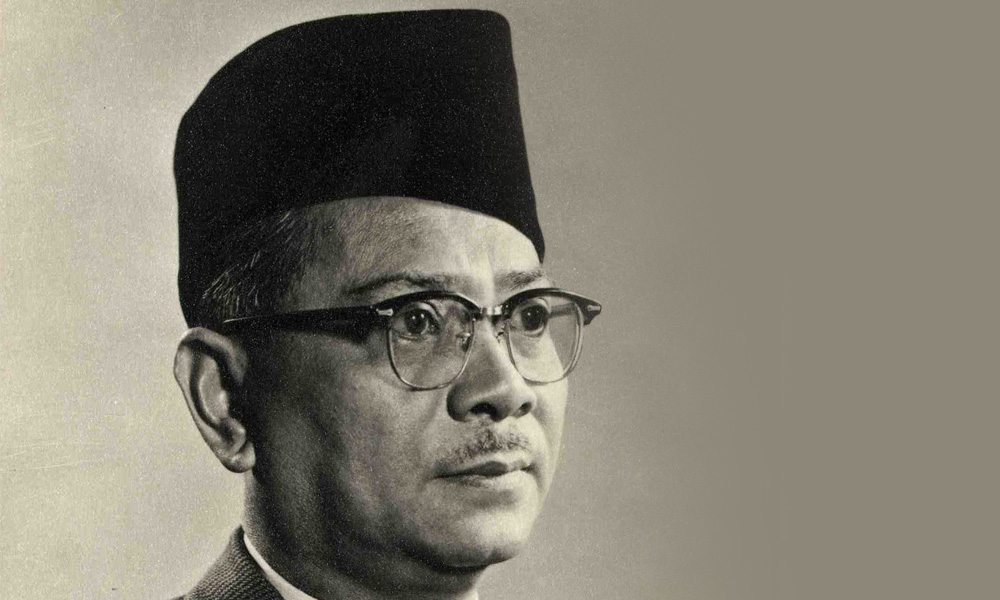

Although this was possible, the late Tunku Abdul Rahman (photo, below) was not inclined to such a course. He preferred expulsion. Now, having seen the back of Lee Kuan Yew, Devan Nair was looked upon as his sole spokesman in Malaysia. Whenever and wherever Devan Nair addressed public rallies, people thronged to hear him as if he was carrying some message from Lee Kuan Yew.

When Lee Kaw, the first DAP member of the Johor legislative assembly, and I, with few others, decided to form a DAP branch in Kluang, followed by other branches in the north of Johor, Devan Nair attended some of our public rallies.

Going to one such rally in Kluang and seeing the huge crowd, Devan Nair jocularly remarked, “Shall I tell them (the crowd) that I have no message from Kuan Yew?” Devan Nair accepted the political reality of the day. His continual presence in Malaysian politics would be exploited by DAP adversaries to hamper its growth as a strong opposition to the Umno-dominant Alliance.

In fact, by 1968, Devan Nair reduced his DAP political activities in Malaysia, and Goh Hock Guan emerged as the secretary-general of the party. The Malaysian Parliament was dissolved at the end of the first quarter of 1969, paving the way for a general election in early May.

Devan Nair, as Malaysia’s torch-bearer of democratic socialism, decided to pass on the torch to Dr Chen Man Hin, Goh Hock Guan and Kit Siang. Devan Nair would return to Singapore to continue with his crusade in trade unionism.

During the formative years of DAP, Kit Siang and I would travel in his Fiat 1100 to various parts of Johor to establish DAP branches. The 1969 general election came and the results showed that the opposition had made significant inroads into the then Alliance’s strongholds.

The Socialist Front had earlier decided to boycott the election. It was the final political hara-kiri the Labour Party of Malaya committed. It paled into oblivion and eventually disappeared from the Malaysian political scene altogether. DAP established itself as a party with an appreciable following in Malaysia and a force to be reckoned with.

Election results in Penang showed that the opposition Gerakan had gained a majority of seats to form the state government. In Perak and Selangor, Alliance lost its majority and the signs were clear that the opposition coalition could form state governments. The Alliance could not wrest Kelantan away from PAS.

However, riots broke out on May 13. Kit Siang had, on the morning of May 13, 1969, left Kuala Lumpur for Sabah to assist the election campaign of a panel of independent candidates in Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan and Tawau. It was whilst speaking at a public rally at Kota Kinabalu on the 13th night that he learnt of the riot on the same day. On May 14, 1969, Kit Siang was served with an order to leave the state of Sabah as he had criticised Mustapha Harun, the then chief minister of Sabah, at a public rally.

As there was only one flight then between KL and Sabah, Kit Siang took the flight on the following day, May 15, 1969, and landed in Singapore as KL was under curfew and the Subang Airport was closed. Kit Siang returned to KL on May 18, 1969, and was arrested upon landing.

The May 13 riots had caused immeasurable damage, with loss of lives and property. Many reasons were attributed to the cause of the riots, and lies, fabrications and distortions were aplenty. One of those false and fabricated ones was that Kit Siang had provoked the riot by his conduct and this falsity has been perpetuated among the Malays - up till now.

The actual reason, as truth unfolded, did show that neither DAP nor its leaders were the cause, but the loss of power in certain states and the diminishing people’s support led some irresponsible persons to ignite the riots.

A state of emergency was declared and Abdul Razak Hussein was made the director of the National Operations Council. Parliament was suspended, and with it, all fundamental rights guaranteed by the constitution were also suspended.

In the meantime, Razak brokered a coalition of all parties in the country, both in Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia, hence Gerakan led by Dr Lim Chong Eu, PPP then led by SP Seenivasagam, and PAS and other parties came under one umbrella called Barisan Nasional (BN).

DAP stayed out. Had DAP joined the BN at that time, the then leaders of DAP such as Dr Chen Man Hin and Lim Kit Siang would have been made federal ministers. Aside from that, the party would also have found itself in the state executive councils, at least in Perak and Selangor.

But DAP elected to stay away from BN as it was alleged that there were some differences between MCA and DAP over the number of ministers each party should have. The friction was put to rest when DAP firmly chose not to join BN. Soon after this development, Goh Hock Guan resigned from DAP as a result of which Kit Siang became the secretary-general. Hock Guan’s departure did not have any impact on the party.

As for me, I decided to read law and, in late 1974, I left for England.

In 1976, Kit Siang came to London to take his final Bar examinations. He had begun to read law while in detention. I had not seen Kit Siang ever since his detention following the May 13 incident. The meeting between us in London was a reunion after a long period. I managed to get him a room in the London House at Mecklenburg Square, where I had been staying.

The Bar examinations came and Kit Siang was very enthusiastic, energetic and very confident that he could make it through. The first day was good. He was happy with his performance. The second day, too, saw his confidence peaking the height of delight. The third day of the examinations got him feeling hopeless and miserable. According to him, he had fared poorly in that day’s examination paper. We had a long chat over dinner. He was determined to give up. I told him that he should concentrate on the remaining papers and not brood on his performance in one paper. Would he listen? It was too difficult to change his mind.

During his brief stay in London House, Kit Siang would come to see me at about five every morning to collect hot water. When we took leave after dinner on the evening of his disappointing performance, I told him, “I will see you in the morning Kit. Good night.” His reply was not convincing, but I had a feeling he would show up.

At five in the morning, as I had expected, Kit Siang came to collect hot water. I then knew that he would complete his remaining papers. “Okay. Since I’m already here, let me finish it,” he said. He finished the remaining examination papers and before leaving for home he left some cash, his examination index number and his house telephone number to contact him once the results were out.

The results were out and Kit Siang passed with distinction. Shocking. Here was a candidate who was on the verge of throwing in the towel, yet had made it with astounding excellence. I called Kit Siang and informed him of the splendid results. What did I get? “Stop Sila. Don’t joke.”

I repeated the result, yet he wouldn’t believe. “Are you drunk?” was another insinuating arrow from him. He asked for the index number, which I repeated. Correct. Name, "KS Lim". No! That’s not my name, was his response. I told him that the Bar Council would not publish the full name. Still, he wouldn’t believe. The conversation ended. About half an hour later Kit Siang called and interrogated me further on the results. Kit Siang was not in a mood to believe me.

A few days later, I received a telegram from Kit Siang. He was coming to London and requested that I meet him at Heathrow. From the time I received him at the airport and during the train journey to Chancery Lane, his suspicion did not abate. He was under the impression that something was amiss. He was sure that he had failed a paper, so how could he pass with distinction?

I remember it was a Saturday when he arrived in London. We got down at Chancery Lane. He insisted that we go to the Inns of Court’s office to see the results. It had been a few days since the results were published. The notification may have been taken down. We went to the Inns of Court’s office at Gray’s Inn. It was closed.

On Monday, he went to the Lincoln’s Inn Treasury and, to his delight, learnt that he had indeed passed with distinction. That was not the end of the matter. He wondered whether he could see the paper that he had miserably performed and understand how it was marked. I laughed at his strange attitude. “They won’t show you,” I said.

Kit Siang was called to the Bar of England and Wales, and when he left for home, he was still unsure how he got through with distinction. That was Kit Siang, a man with steely determination and who believes in impeccable performance.

I have always found him to possess dedication in whatever he does. He is never satisfied with his own performance. On being successful in effecting a change of government with the cooperation of other parties at the last general election, he was modest, displaying his inherent disassociation with false hopes. I was not surprised when he said, “I am surprised we won.”

That is Kit Siang, Mr Perfect.

K SILADASS is a practising lawyer.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.