When his village in the Buthidaung township in Myanmar’s Rakhine State burned down during the violent clashes between local Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims that began in 2012, Tobarik Hason and his younger sister fled.

“The situation was chaotic. We were running... and we were separated from the rest of our family. A few days later, we found our way to Maungdaw [another town in Rakhine],” the 19-year-old said.

Spying a boat they hoped would take them to safety, the two siblings “just got on it”.

They arrived in Malaysia in 2013, but were arrested for entering the country illegally as they crossed the Thai border in a vehicle carrying 10 to 15 other people. They spent 14 days in a police station before being sentenced to three months in jail and a stroke of the cane. Then, they spent two years in a detention centre while waiting for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to verify their status as refugees. Separated when they were put in gender-specific quarters, they didn’t see each other again until they were released in 2015.

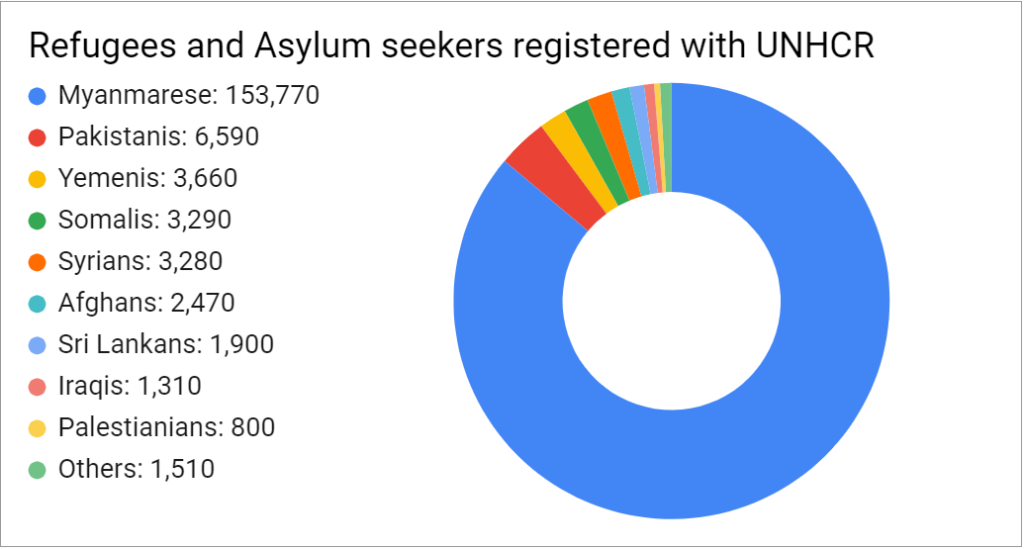

Tobarik and his sister are among the estimated 98,740 Rohingya in Malaysia; the Rohingya are the largest group of the 178,100 registered refugees and asylum seekers in the country.

As of end December 2019, there are some 178,580 refugees and asylum-seekers registered with UNHCR in Malaysia.

Lives torn asunder

The Rohingya have been fleeing Myanmar in droves because the Burmese government, which sees them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, has for decades subjected them to institutionalised discrimination and repeated state-sanctioned violence.

The Rohingya are neither recognised as citizens nor as one of the 135 official ethnic groups in predominantly Buddhist Myanmar despite their historical presence in the region purportedly dating back to the 15th century.

The Burmese government has also labelled the Rohingya - using insurgent group Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army as an example - as an extremist threat that needs to be dealt with as such.

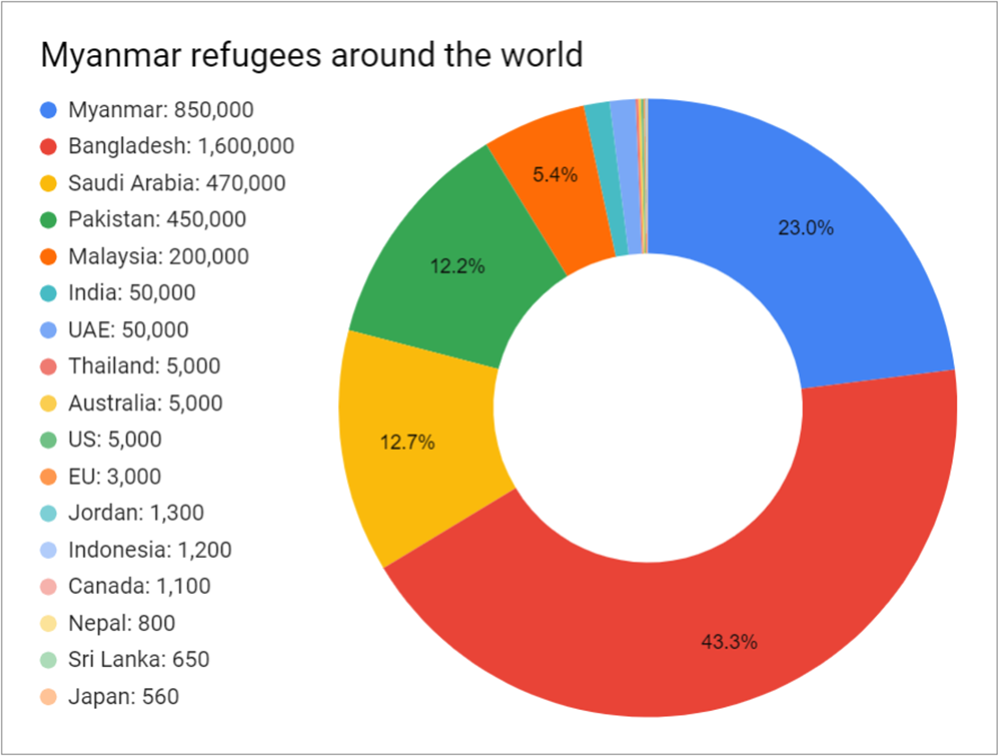

The most recent wave of violence against the Rohingya started in 2017 and sent over 700,000 people fleeing across the border into Bangladesh’s refugee camps. It was so bad it has been described as genocide by human rights organisations and, recently, by the International Court of Justice.

Yante Ismail, a UNHCR officer in Malaysia, says the Rohingya have been coming to Malaysia for decades, with the largest migrations being in the 1990s. Most made their way from Rakhine State, others from Bangladesh’s refugee camps. Many borrowed money from friends and family - roughly RM6,000 to RM7,000 - to pay their way, to avoid being beaten or sold into forced labour.

Some have been resettled in other countries like the United States and Australia, but many have remained in Malaysia and built a semblance of a life here. After Bangladesh, Malaysia hosts the largest number of refugees from Myanmar - most of them Rohingyas.

Making the best of limbo

Twenty-year-old Mohamudul Hasson never even knew Rakhine State. He was born a refugee in the Nayapara refugee camp in Bangladesh, which his parents had fled to in the early 90s.

Mohamudul seemed a promising student, but the Nayapara refugee camp only offered informal primary education. So, he tried to pass himself off as a Bangladeshi in order to get a secondary school education outside the camp.

But a classmate saw him coming out of Nayapara one day, and his school soon expelled him - a fate he says is not uncommon for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. And it wasn’t just education opportunities that were lacking - life itself was as constrictive as a straightjacket.

“In Nayapara, you are not allowed to express your feelings. You are not allowed to do anything,” he said.

In February 2015, something broke inside him. With little more than the clothes on his back and without even telling his family – he knew they would tell him it was too dangerous – Mohamudul boarded a smuggler’s boat and headed for Malaysia.

But things didn’t go as planned. A fight broke out among the passengers on his boat, causing it to capsize and sink off the coast of Aceh, Indonesia. For nine months he stayed at a refugee shelter there, but eventually managed to make his way to Malaysia by boat in February 2016.

Mohamudul ended up in a community of local Malay, migrant Indonesian, and Rohingya refugee families in Batu Caves, Selangor, where he met Tobarik. They lived with other Rohingya families with children and paid roughly RM300 to RM500 a month for food and lodging.

Since then, the duo has counted each other as friends, chatting over coffee with fellow refugees while watching Bollywood movies at a makeshift cafe, or playing sepak takraw on the communal grounds.

Grey areas offer slivers of hope

Malaysia is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and has no legal framework to manage refugees. “Under Malaysian law, refugees are considered illegal immigrants. This means they are at risk of arrest and detention if they are caught by the police,” said Yante.

But the government does, on humanitarian grounds, cooperate with the UNHCR to address refugee issues. Agency-registered refugees or asylum seekers get a UNHCR identity card that offers them some basic legal protections.

“They get 50 percent off foreigners’ rates in public hospitals. And if there’s a raid on illegal immigrants and they are detained, we can advocate for their release, and the police will often let them go,” Yante said.

And though refugees and asylum seekers are not officially allowed to work or access public education, the Malaysian government mostly turns a blind eye to them doing so informally. UNHCR and its NGO partners, as well as the refugee communities themselves, have worked together to set up ad hoc educational facilities. It’s nowhere close to enough though - secondary and tertiary education is still severely limited.

Despite this, Malaysia continues to draw young Rohingya refugees hoping for a shot at studying or working. About a quarter of the almost 100,000 Rohingya refugees registered with UNHCR in Malaysia are children younger than 18.

For the love of football

Like Mohamudul, 22-year-old Shamizullah Shanwary (below) grew up in Bangladesh’s Nayapara refugee camp.

He arrived in Malaysia in 2015, a month after leaving Bangladesh by boat. As the eldest son, Shamizullah felt the responsibility to provide for the family he had left behind in the refugee camp.

But he also just wanted to be able to play football more freely.

“In a refugee camp, I can’t be anyone or anything. We had no education, we had no play. But if I take the risk to leave, maybe I can be someone,” he said.

For a while, he bounced between Selangor and Terengganu and did odd jobs - working at a car wash and at a wet market - before receiving a call that raised his spirits from an old Nayapara friend, Aman Ullah.

Aman wanted him to join the new football club he was starting, the Rohingya Rose Football Club.

“He was one of the best football players at our camp and won the title of ‘Man of the Tournament’ many times. He was even asked by Bangladeshis to play in football matches outside the camp, though sometimes he wasn’t paid for it,” said Aman.

“So when I was going to start the club and heard he was in Malaysia, I found his number and called him.”

“In a refugee’s life, football can help release stress when you feel alone. When we play we don’t talk about sorrowful memories or family and all that,” said Shamizullah. “I got a voice when I came here.”

Love, loneliness and belonging

Loneliness also hits Tobarik hard. He said the worst thing about being in Malaysia is being without his family, especially now that his sister, who got married in 2017, no longer lives with him.

But Mohamudul, the boy who left his family behind, is beginning to build his own. He works for the Geutanyoe Foundation, helping refugees access medical treatment and helping to run a programme teaching women the basic communication skills needed to navigate outside their homes. He recently married a fellow Rohingya refugee, who works as a teacher for the same foundation.

“We want to make sure that our marriage isn’t like arranged marriages, and that we don’t just get divorced after a few months.

“We feel like we can stay together. We really love each other. Here in this country, everyone is choosing their own life partner,” he said. “I feel the freedom here which I didn’t feel in Bangladesh.”

These young Rohingya men have found ways to rebuild their lives through informal networks, but in the absence of a coherent national policy, individual refugee experiences vary; they are dependent on the goodwill of strangers and vulnerable to exploitation. “Every aspect of their lives is insecure and unpredictable,” says Yante.

The milk of human charity doesn’t always flow freely. A recent survey by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute found that 56.4 percent of Malaysians are not in favour of the Rohingya being resettled in the country.

However, the Malaysian government has been outspoken in calling for justice for the Rohingya, and for action by Myanmar to address the community’s issues.

A few months ago, Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah signalled the country’s new commitment to protecting refugees when he announced that a “national plan” for Rohingya refugees is being discussed.

”Malaysia has come a long way in our discussions and thinking on refugees. There’s really a huge improvement from where we were, say, 10 to 15 years ago, when there was an absolute reluctance on the part of the government to discuss the issues of refugees. Now, there’s a lot of discussion among government ministries and agencies, including at the higher level, on what the right approach would be for Malaysia,” said Lilianne Fan, international director of the Geutanyoe Foundation.

'Do it, even if we can’t'

Not long after he was released from detention in 2015, Tobarik (below) managed to find a job at a car wash near where he lives. He worked from 5am to 5pm every day, with only half days off on Sundays. His salary? A mere RM1,200 per month. And a slice of that salary went to paying a friend to whom he owed money for his passage to Malaysia.

He vividly remembers the day he received his first paycheck. It helped him to find his family in Rakhine, with whom he had lost touch after he and his sister were separated from them.

He bought himself a phone and, in three months, managed to track down his father’s whereabouts and phone number by asking friends of friends.

“When I finally called them, my parents cried. They had not heard from us for almost three years. They thought we were dead,” he said.

“My mum cried a lot when she first heard from me. Even now, she can’t take it. She asks, ‘So, you can live there? You can do it?' And I tell her, even if we can’t, where can we go? Even if we can’t, we have to do it."

This article was originally published on Between The Lines, a weekday newsletter that curates the most important news stories of the day and explains the context behind them. Subscribe for free here.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.