COMMENT | When we talk about electoral constituency boundaries, words such as malapportionment and gerrymandering do pop up in our minds.

We, Tindak Malaysia, have been championing fairer boundaries for all Malaysians since 2011. We are strong believers that rectifying malapportionment will pave the way for fair boundaries for all.

At the same time, we also came to a recent conclusion that fair boundaries are not just about sensible boundaries and equitable electorate sizes. As we were at the forefront of the Polling Agent, Counting Agent, Barung Agent (Pacaba) training since 2008, the main activity that takes place in a constituency in elections is the polling centres.

Our recent research for the past three years has shown our constituencies and their building blocks (polling districts) were drawn without proper consideration of available polling centres.

This violates Schedule 2(b) of 13th Schedule (guiding schedule for redelineation) - “regard ought to be had to the administrative facilities available within the constituencies for the establishment of the necessary registration and polling machines”.

In this article, we shall explore this hidden violation in depth.

Contextualising Schedule 2(b) for redelineation

Essentially, in reviewing the division of constituencies (or redelineation), the Election Commission (EC) would have to consider the availability of necessary infrastructure and facilities required for voter registration and polling. This would be to ensure that each constituency would have sufficient polling centres for a fair and equitable vote.

Although such a provision existed in the Constitution, transparency on this issue alone is often difficult. Under See Chee How & Anor v Pengerusi Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya (Election Commission of Malaysia) [2016] 8 MLJ 384, it was held that in order to disclose the “effect” of its recommendation, the EC should disclose in its notice, among others:

- The proposed electoral roll;

- The exhaustive list of changes to the parliamentary and state (DUN) constituencies;

- The polling centre districts on the map;

- The administrative, physical and infrastructural boundaries on the map;

- The electoral size; and

- The landmass of the proposed constituencies.

However, this was short lived. The Court of Appeal overruled the High Court’s decision stating that a notice without such particulars was enough, as interpreted by the literal reading of the Constitution.

Despite polling districts being the fundamental reference point of a voter, being denied of the knowledge of which polling district the particular voter would be under, along with the non-disclosure of electoral roll, renders the voter ignorant of his own polling district, and opens the backdoor of gerrymandering.

It is the responsibility of the EC to divide constituencies into polling districts after a redelineation whereby polling centre or centres are to be appointed for each polling district (Election Act 1958 Regulation 7).

The division of polling districts can be altered as the EC sees the need to divide, and such changes including polling centres must be notified via gazette. Unless it is necessary or expedient for special circumstances, each polling district has a polling centre.

The EC also has the powers to replace the original polling centre with a new polling centre subject to the arising needs.

There are a few flaws in Election Act 1958 Regulation 7. Firstly, there is no rule that a polling district needs its polling centre to be within the said polling district. Secondly, it is possible two polling districts can share the same polling centre.

As we look into case studies, these deficiencies create a faulty base for the EC to delineate constituencies during the redelineation exercise.

In the post 14th general election (GE14) era, we, Tindak Malaysia, came to realise the greater importance of Schedule 2(b). Few major changes took place after GE14. Firstly, is the coming implementation of Undi18 (together with automatic voter registration) which brings a minimum of 5.6 million new voters into our electoral roll.

Secondly, new improvements ought to be made to increase voter accessibility in the polling centre areas. Since the Cameron Highlands by-election in 2019, all disabled voters registered with Welfare Department are channeled to the first voting stream (or saluran in Malay) which is the same stream for the elderly.

For the Kimanis by-election, the EC invested its own money to improve the pavements in polling centres so that elderly and disability voters can access the voting stream with ease.

However, some challenges for the elderly to vote were felt in the recent Sabah state elections. In the Luyang constituency (Kota Kinabalu), a sudden change in voting location within the polling centre created inconveniences as elderly voters had to walk down a steep hill.

Thirdly, the number of voting streams have increased since GE14. The maximum number of voters per stream was reduced from 750 to 600 per stream in the post GE14 era. Such a move would result in an addition of 13,000 streams (nearly a 50 percent growth from GE14). This can facilitate a much faster voting process.

In addition, with the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of voters per stream was further slashed from 600 to 400, which took place in the Chini by-election. The major question in this issue is whether our current allocation of polling centres is ready to cope with such growth in voting streams.

Violation when no alteration to boundaries occur

Let’s look into some examples where the 2016-2018 redelineation exercise fails to address Schedule 2(b).

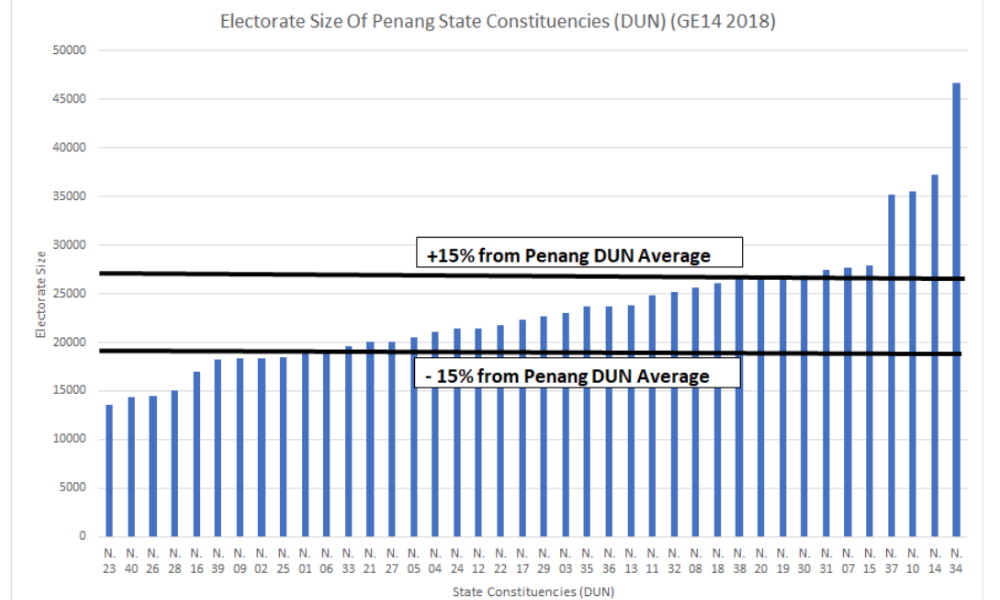

Here, hardly any state constituency or parliamentary seat boundaries of Penang were altered, despite there being a need to address the gross malapportionment of the seats. Similarly, the said seats do not respect local ties.

The boundaries of polling districts, state and parliamentary seats that were used in GE14 were laid down during the stealth redelineation exercise in the earlier part of 2016. These boundaries were largely retained when 2018 redelineation was approved albeit minor changes in boundaries and names of a few polling districts.

The Air Putih state seat (Parliament of Bukit Bendera) - Lim Guan Eng’s seat - had seven polling districts in GE14 where polling centres of the four polling districts were found in neighbouring Air Itam constituency (Parliament of Bukit Gelugor).

Out of 13,509 voters in GE14, close to 80 percent of the voters of Air Putih had to cross DUN and parliamentary boundaries to cast their ballots in the polling centres found in Air Itam.

While the EC had the powers to find appropriate polling centres for Air Putih after the 2018 redelineation, no effort has been made. The root cause of the issue was that the polling districts were drawn in Air Putih with no reasonable considerations of polling centres in each polling district.

Moreover, as voters of Air Putih cross over to Air Itam to cast their ballots, these voters would have crossed paths with Air Itam voters who were making way to their local polling centres. Why was Air Putih drawn without proper consideration of available polling facilities?

Violation when alteration of boundaries occur

How about constituencies which experienced gerrymandering? Let’s take the example of Semenyih (Parliament of Hulu Langat).

The Semenyih seat experienced the removal of polling districts thanks to the 2018 redelineation exercise. These polling districts exhibited strong Pakatan Rakyat/Harapan preferences. Two new polling districts - Kantan Permai and Penjara Kajang - were added to Semenyih even though they hardly have good connectivity with other parts of Semenyih.

The assigned polling centre of Penjara Kajang was neither within the Penjara Kajang polling district nor anywhere in Semenyih. This polling centre was found in the neighbouring parliamentary seat of Bangi.

Not only did the Semenyih constituency violate local ties, one can argue it also violated Schedule 2(b). Were there no polling centres available within Penjara Kajang? Or why Penjara Kajang was drawn in a way where there are no inhouse polling centres?

These examples are tips of the iceberg. A violation of Schedule 2(b) in any given state or parliamentary seat is the main fingerprint of the greater problem of voter allocation to polling centres throughout the country.

Moving forward

With huge changes to take place on our electoral roll and voting experience, the EC must take proactive measures to ensure sufficient polling centres are available in every given constituency.

We have proposed to the EC that the polling districts ought to be drawn where two polling centres can be identified and accessible to all voters. We have submitted such concerns to the EC for seats of Kimanis (Sabah), Sandakan (Sabah), Luyang (Sabah), Semenyih (Selangor) and Beseri (Perlis).

Moreover, as the EC made great steps in improving accessibility for voters, future polling centres need to be more accessible and friendly for the disabled and elderly community.

In coming redelineation exercises, the EC must provide the necessary assurance to voters that there are enough polling centres in a given constituency. As voters, we ought to lobby all tiers of government to have our schools, halls, and community centres (all potential polling centres) to be accessible for all members of society.

Redelineation is not just about sensible boundaries and equitable electorate size, but ensuring constituency facilitates voting for all.

DANESH PRAKASH CHACKO is Tindak Malaysia’s director and research analyst at the Jeffrey Sachs Centre on Sustainable Development (Sunway University).

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.