LETTER | I read with interest Francis Paul Siah’s Come on, Malaysia, let’s twist again.

What a twist it has been for the year’s Opening of The Legal Year (OLY). Unfortunately, to say the least. It should have been remembered as an occasion to celebrate a number of historical significances.

It was the 10th edition. It was the attorney-general’s and the chief justice of Malaysia’s maiden OYL event. Significantly also, it marked the Malaysian Bar’s return to the auspicious event after giving it a miss in 2018.

Having said this, I still think that it should have been a red-letter occasion not only for the above. It should have marked the start of a new legal year against the backdrop of a decade of judiciary-initiated reforms that even the World Bank has acknowledged.

The Malaysian judiciary, like its counterparts in many jurisdictions, has had its fair share of the evils. Two of these are the backlog of cases and delays in the litigation process – the so-called twin evils. To its credit, the judiciary did acknowledge the problems and took measures to deal with the same, with reforms introduced at the turn of the new millennium.

Until October 2008 these reforms, however, were few and far between and not sweeping in nature. It was during the tenure of chief justice Tun Zaki Azmi, who took on the mantle as head of the judiciary in October 2008, that the reforms were more aggressively pursued.

The success story of his lordship’s reform is already well-documented by many, foremost by the World Bank (Malaysia: Court Backlog and Delay Reduction Program – A Progress Report, 2011).

Prof Choong Yew Choy of the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya recorded Zaki Azmi’s accomplishment as follows (in JR Yeh and WC Chang, eds. Asian Courts, 2015):

“Within a relatively short period of three years, chief justice Zaki overcame the problem of the backlog of cases and has put in place a system where all new commercial and civil cases are now disposed of within nine months. Zaki Azmi achieved this by taking a step back to understand the underlying problems and then set out to work tirelessly with his fellow judges to overcome these obstacles.

“The strategies adopted by chief justice were not by any definition radical. They were in fact very simplistic and straightforward. However, these strategies were highly effective. The success of these reforms can be attributed to the unwavering commitment and desire on the part of the chief justice and his fellow judges to improve the overall system.”

As a matter fact, Zaki’s successors took on his reform initiatives and ensured that the reforms were continued unabated. Curiously, while Zaki was mentioned in present chief justice Richard Malanjum’s salutations at the OLY 2019, his two immediate successors were not.

I do not wish to dwell on this. But let’s just step back and look at the ten years from 2008 to 2018. I would call it a decade of reforms.

In its flagship “Doing Business Report” for 2019, the World Bank has ranked Malaysia 15th overall, nine rungs up from 24th place in the previous edition of this annual series that is now in its 16th year.

For the uninitiated, the World Bank’s “Doing Business Report” is a project that provides objective measures of business regulations and their enforcement across 190 economies and selected cities at the sub-national and regional level. Doing Business 2019 provides 11 quantitative indicators, one of which is enforcing contracts.

This indicator (enforcing contracts) measures the following:

- the time and cost for resolving a commercial dispute through a local first-instance court;

- the quality of judicial processes index, evaluating whether each economy has adopted a series of good practices that promote quality; and

- efficiency in the court system.

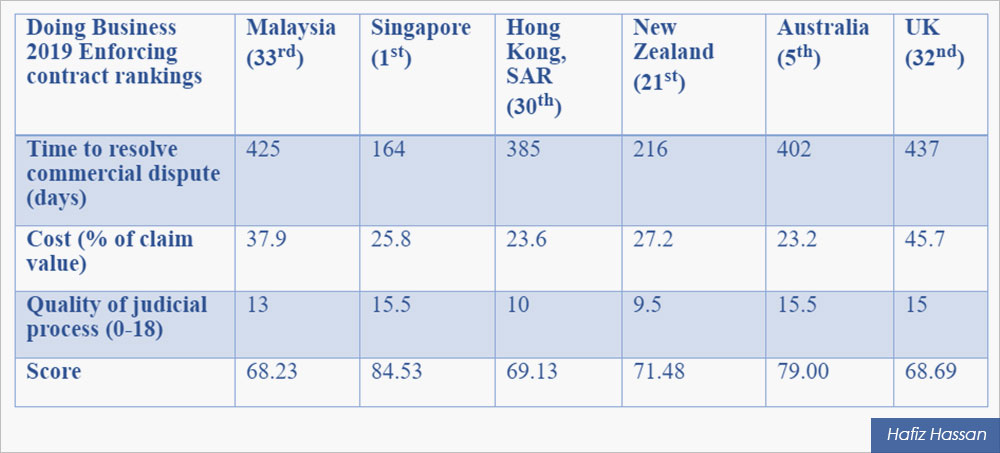

Malaysia is ranked 33rd for enforcing contracts and its measures of quality can be seen in the following table:

Malaysia is only second to Singapore but there is a lot of catching up to do with its neighbour across the causeway.

As for common law jurisdictions, Malaysia stands as follows:

There is something noteworthy from the above. Malaysia’s score for quality of judicial process (a commendable 13 out of 18) is better than Hong Kong and New Zealand. It is also only behind China (15.5) and South Korea (14.5) who are its competitor economies as the following graphics show (Doing Business 2019: Malaysia):

The above should fittingly be celebrated at OLY 2019 – if only the legal profession had read beyond the legal texts. But, again, let’s not dwell on such oversight in as much as we should not dwell further on the twist.

There’s much work to do and be done for 2019. For one, the time to resolve commercial disputes through a court of the first instance (Kuala Lumpur Magistrates’ Court) is currently 425 days as shown in the table below:

Malaysia can certainly do better. It can and should shorten further the number of days for trial and judgement as well as well as enforcement of a judgment.

So, let’s do better. And perhaps for OLY 2020, the legal profession can indulge in another celebratory dance.

No, not the twist again. Perhaps a joget.

Author's Note: The figures above are compiled from the World Bank’s "Doing Business 2019" report for the respective countries and were presented at the China-Asean Civil and Commercial Law Forum 2018 at the Guangxi Universities for Nationalities, Nanning, China.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.