SPECIAL REPORT When successful migrant Nazmun made his way to Malaysia from the lush village of Araihazar in rural Bangladesh, the cost was about RM1,500 and his pay was RM40 a day.

Twenty years later, Seron, a youngster from the same village, snuck his way to Malaysia via the sea, forcing his family to pay smugglers RM11,000 to secure his release after he was held in the Thai jungle after the treacherous journey.

Seron’s pay was not much higher than Nazmun’s.

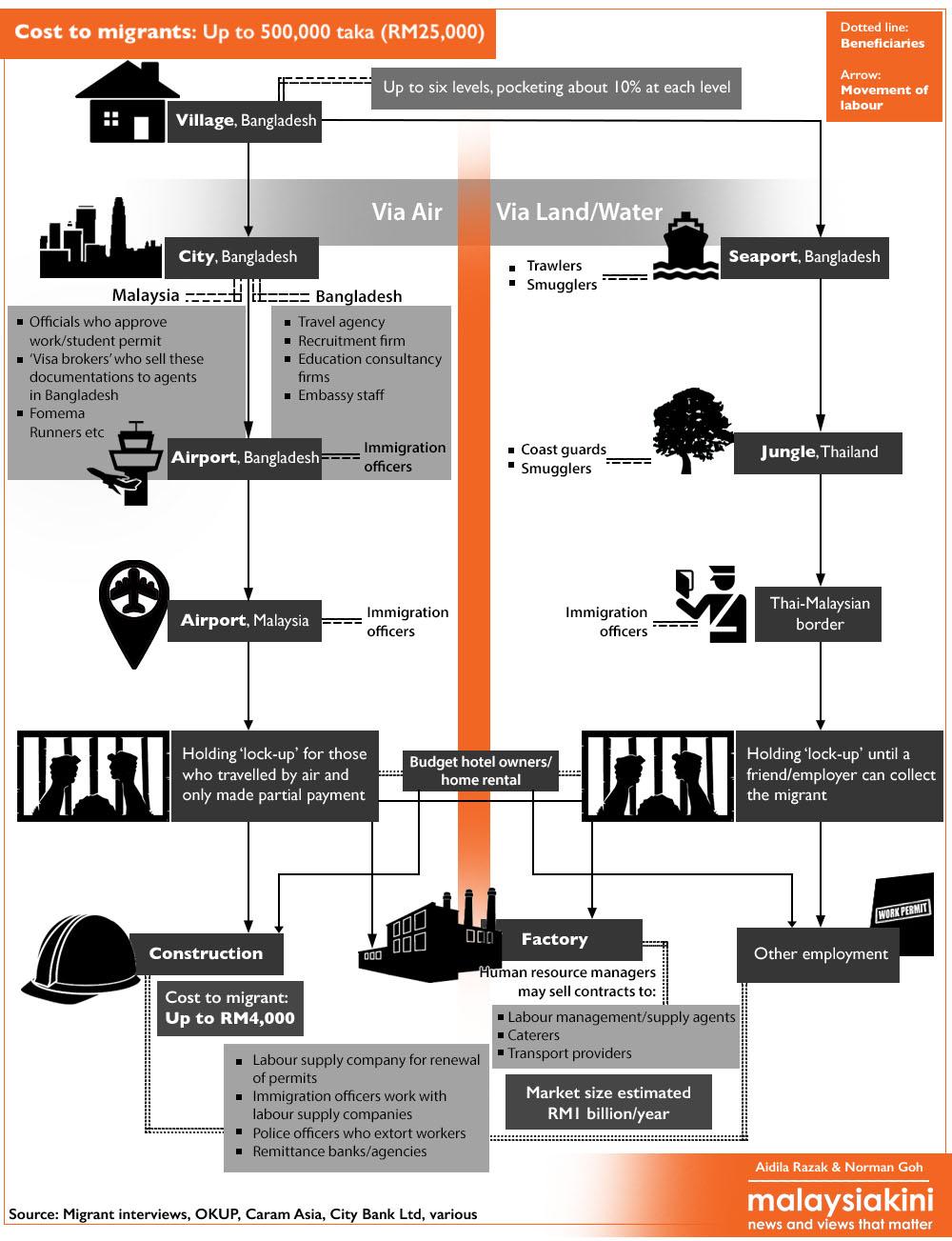

The sharp spike of migration cost for Bangladeshis heading for Malaysia since the 1990s can be attributed to the growth of the recruitment industry, said Muhammad Harun Al Rashid.

Harun is a coordinator at regional advocacy group Caram Asia and has studied the migration of Bangladeshis to Malaysia for two decades.

The beneficiaries, he said, are not just Bangladesh recruitment agents but outsourcing firms in Malaysia, seen as the answer to the growing demand for foreign workers by industries in the country.

Permits were issued to these firms, but poor monitoring and corruption allowed some firms to bring in workers, without ready employment.

Department of Statistics data show that in 2007, there were just over 62,000 Bangladeshi workers in Malaysia. In 2008, the number jumped by more than 250 percent to 217,238.

Department of Statistics data show that in 2007, there were just over 62,000 Bangladeshi workers in Malaysia. In 2008, the number jumped by more than 250 percent to 217,238.

“There was a mess everywhere, from the Kuala Lumpur International Airport to the Bangladeshi Embassy, at the roadsides, everywhere,” Harun said.

Bangladesh Association of International Recruitment Agencies (Baira) vice-president Ali Haider Chowdury remembers this period well.

“I sent 300 workers to Malaysia at that time, and they were left on the streets. After that, I said, ‘no more’.”

Official statistics tip of the iceberg

The Malaysian government froze the general worker visa for Bangladeshis in 2008. Similarly, Chowdury said, registered Bangladeshi recruitment firms have not been sending general workers to Malaysia.

This means none of the many layers of agents, as described by Nasim Ahmed of the Dhaka-based migrant rights NGO Ovibashi Karmi Annayan Program (Okup), work for registered recruitment agents but Baira gets all the flak , Chowdury said.

A year after the freeze, the number of Bangladeshi general workers jumped by 99,168.

In 2013, the number of Bangladeshi workers with temporary working passes in Malaysia stood at 322,750 - almost double the population of Shah Alam.

But the numbers cited by the Bangladesh remittance bank City Bank Ltd (CBL) when it opened its doors in Kuala Lumpur the same year tells a different picture.

"There are more than one million Bangladeshi workers in the country and another 1.4 million workers are expected to enter the country," CBL chairperson Aziz Al Kaiser told reporters at the opening of CBL’s Malaysia branch at Leboh Pasar Besar in Kuala Lumpur, as reported by The Malaysian Insider .

Most of these workers enter the country using tourist, student and skilled professional visas, with the help of travel agencies and education consultancy firms. There are also many who travel by sea and slip into Malaysia, without any documentation.

Although some are duped into working in hotels as cheap labour, many of these Bangladeshis, said Nasim, apply for student visas with the intention to work.

Students who can’t spell ‘student’

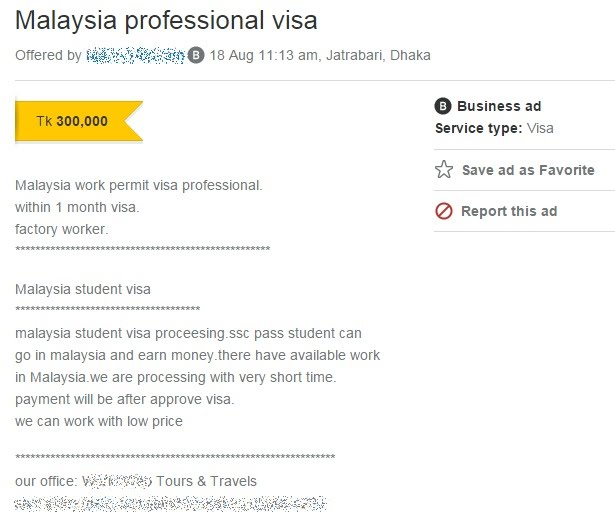

A classifieds advertisement put up by a travel agency in Dhaka in August 2015 is telling. It states:

“Malaysia work permit visa professional. Within one month visa. Factory worker/Malaysia student visa processing.

“SSC pass student can go in Malaysia and earn money. There is available work in Malaysia. We are processing with very short time. Payment will be after approve visa. We can work with low price.”

The price: 300,000 taka (RM15,000)

The latest statistics from the Ministry of Education show that in 2013, 2,442 Bangladeshi students were enrolled in private and public universities, much lower than what officials in Dhaka told The Dhaka Tribune newspaper last year.

Officials at the Dhaka International Airport estimate that on average, 200 people “who are neither tourists nor students” travel to Malaysia on those visas every day, some of whom “could not even write the word ‘student’ but went to Malaysia on a student visa”.

They believe corruption within the Malaysian High Commission in Dhaka is also to blame.

“I have seen visas (held by workers) with public universities listed, but perhaps it is without the public university’s knowledge. The visa holders don’t attend classes, so I don’t know how they worked this out,” Caram Asia’s Harun said.

He said the introduction of the skilled professional visa (DP10) in 2013 was also exploited by agents to send general workers to Malaysia. These visas are approved by the Home Ministry, without any consultation with the Human Resources Ministry, he added.

Harun fears that these DP10 visas will lead to the influx experienced in the days of outsourcing firms - “people are brought in through registered companies which do not have actual operations”.

Under Malaysian regulations, the DP10 visa is only issued to a foreign worker who has secured a job in Malaysia at a minimum salary of RM5,000.

One way an agent in Malaysia can get around it is to register a company, and hire someone at a purported salary of RM5,000 simply to obtain the visa.

The government has not released statistics on DP10 visas issued to Bangladeshis, but a casual search on a Bangladeshi classifieds advertising website led to hundreds of agencies offering such services. One advertisement reads:

“Malaysia professional DP10 Visa. Construction worker. Salary RM2,000.”

The cost of this service: 300,000 taka (RM15,000).

Tomorrow: Fear and hopelessness in KL

Part 1: Debt bondage - chasing the M’sian dream from Bangladesh to KL

Part 2: Land lost, debt-ridden, yet more flow from Bangladesh

Part 3: Why does a construction worker hold a ‘professional visa’?

AIDILA RAZAK is a member of the Malaysiakini team. This four-part series was written as part of the Asia Journalism Fellowship, supported by the Temasek Foundation.