COMMENT | Archival research is, for many of us students of history, the much-beloved backbone of our craft.

Ask any historian about archives and chances are they’ll have some kind of fond anecdote for you – the government clerk who looped his letters with an uncommon flourish, for instance, or that one playful doodle of a frog, tucked into the margin of a naturalist’s notebook.

Oftentimes, it’s within an archive where history tends to truly come alive.

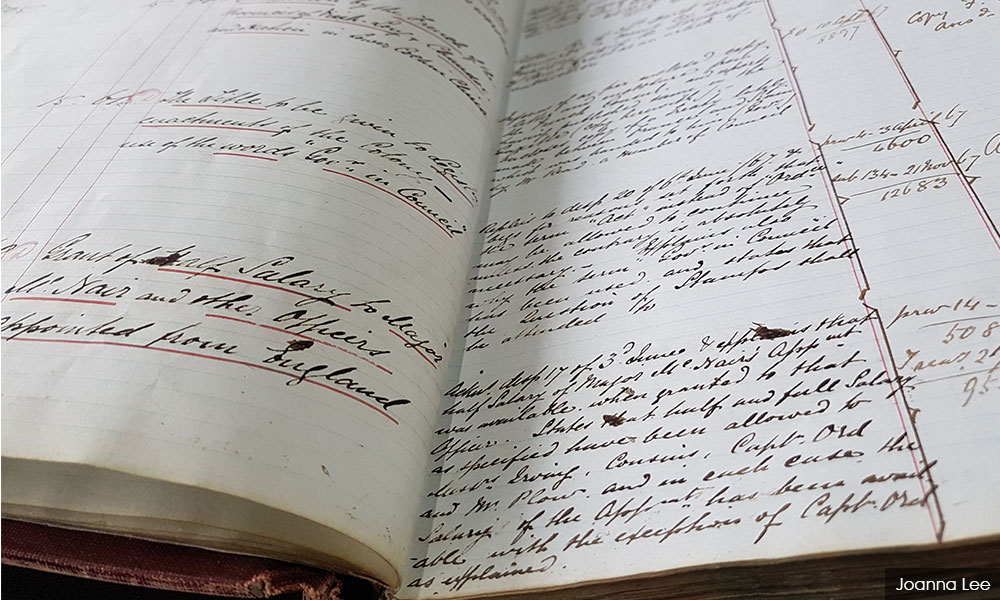

Reading something as simple as a journal entry, one can’t help but be struck by the realisation that a real person, with their own personal histories and living within broader contexts, wrote these words. Real events had to transpire, to urge the keeping of these records.

The obvious thus bears stating in this case: when you (very, very gently) pick up any kind of archival material, you can quite literally hold history in your hands.

Though forming part of a much larger whole, archives are an absolutely integral aspect of studying and appreciating history.

Yet, therein lies the rub for Malaysia.

Archival use not only remains sidelined, but frustratingly inaccessible here, especially when compared against other countries.

After having been intimately acquainted with the process of trying to acquire historical sources from both Arkib Negara and other archives, I can say that I’m making this claim with a certain level of conviction.

A convoluted process

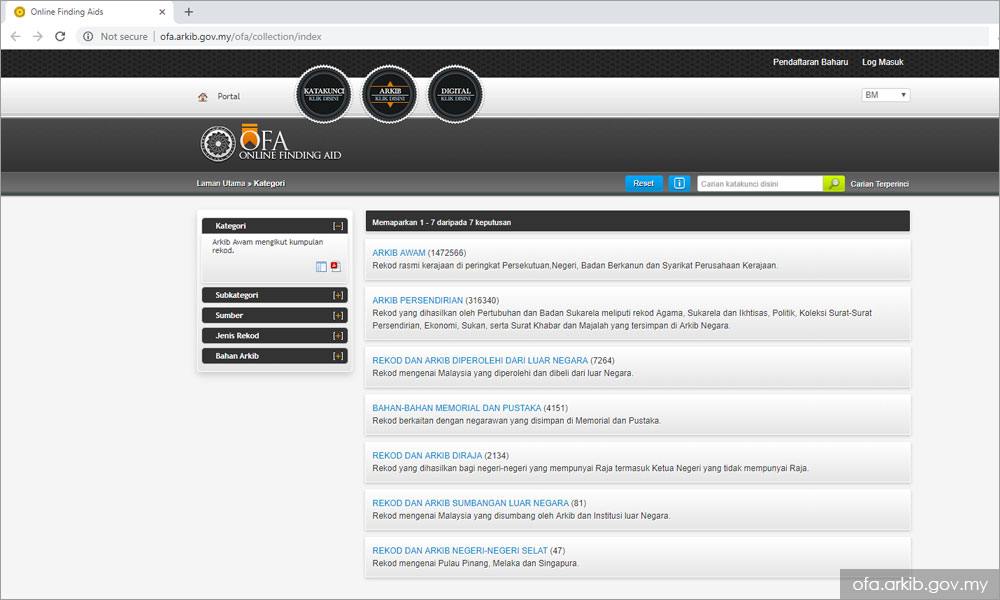

For Arkib Negara, even the process of beginning to search for relevant material online is needlessly convoluted.

On the happy occasion that the Online Finding Aid website deigns to work, record classifications can seem arbitrary at best. At worst, they’re downright incomprehensible.

Take for instance the category of “Straits Settlement Records and Archives (47)”. Now this might lead someone to assume that 47 documents on the Straits Settlements lie within, but following the link, one arrives at “Settlement of Malacca Records (6)”, which in turn leads to three files on St. Michael’s Institution in Ipoh, two on St. John’s in Kuala Lumpur, and one on St. Paul’s in Seremban. Quite evidently, none of these were in the Straits Settlements.

Equally baffling is the website’s internal search engine. Searching within a date range is rendered impossible when the earliest possible input is 2008, while inputting the term “Factory Records: Straits Settlements” – a set of 176 volumes from the East India Company, circa 1786 to 1830 – results in a single, wonderfully bizarre entry: this 1933 file on the preferential treatment of toilet soap manufactured in Singapore.

Technical difficulties notwithstanding, perhaps a more worrying aspect of Arkib Negara is its blanket ban on photographing archival material.

Should anyone wish to copy a document for future reference, charges start at RM0.30 per photocopied page. For digitised items, the same fee for a print-out applies.

This is hardly an astronomical price, but to illustrate how this might translate to a real-world conundrum, consider how in consulting 22 files, amounting to 250 pages, I paid RM75 in printing costs and was handed nearly one kilogramme of papers.

If I’m lucky, these 22 files might form a chapter-section. If I’m not, they’ll be the basis of a mere few paragraphs.

It’s a relatively rare and privileged thing, for researchers to spend entire weeks or months cloistered away in an archive to physically refer to sources as they write.

Those that do have the time and funds to do so are usually senior academics, and even then, this is a subset who can afford to set aside other commitments.

More often than not, archival visits are closer to a hit-and-run, wherein researchers frantically photograph sources to sort through later on our own time, or, if visiting from abroad, when we’re back in our own countries and institutions.

Falling short

Placed in this context, Arkib Negara falls disappointingly short of other archives.

Visiting the National Archives (photo) at Kew in the UK, for instance, I was allowed and even provided the resources to take thousands of photographs of hundreds of files – all for free, and all contained on a microSD card only slightly larger than my thumbnail.

In the State Library of Victoria, Australia, I could save page-captures of entire microfilms to a pen-drive, again for free.

Similarly, the National Archives of India offers unlimited access to thousands of digitised documents that you can freely download as PDFs, all from the comfort of your own home.

Now contrast this to Arkib Negara where, if you’re lucky enough to come across their digitised collections, document previews only extend to the first few pages, with the remainder downloadable upon payment of anything between RM30 to RM100 per file.

Perhaps it’s somewhat unfair to compare such large, presumably well-funded institutions with Arkib Negara. Perhaps this is also just a case of a very specialised complaint, coming from someone whose problems are compounded by living overseas.

After all, who goes rummaging through a dusty old archive anyway, unless they have a thesis, or some other academic work to write? Why even spend time and money on a place that perhaps ten people visit a week?

Accessibility and inclusivity

Admittedly, my initial inspiration for this piece stemmed largely from long-standing personal annoyances with trying to utilise Arkib Negara for my own research.

While its staff have been nothing but helpful and accommodating, the more I interacted with Arkib Negara, the more I came to realise how its overarching structure belies some deeply problematic approaches to who gets access to these sources, and how.

Tangentially, this bleeds into the larger conversations we’ve been having about the state of history in Malaysia.

Not long ago, Malaysiakini published an article by Ranjit Singh Malhi and others regarding the need for an inclusive Malaysian history that incorporates a variety of perspectives. While not intended to be a direct response to this, I might add that inclusion cannot be divorced from accessibility.

After all, how do we include a multitude of voices and perspectives when not everyone can easily access historical sources?

How can we even begin to learn Malaysian history, teach it, or even appreciate its nuances when a bulk of its sources are locked behind these current barriers of confusion, monetary cost, and sheer physical inconvenience? Let us not even mention, at this point, the environmental impact of the latter.

Inclusive histories must be accessible ones, not something to be gatekept by those with the luxuries of funding, time, or even luggage space.

If we are to truly, seriously embark on this monumental task of creating an inclusive Malaysian history syllabus and broader teaching/learning environment, we need to change how we interact with and access local archives.

Archives can contain so much more than the dry, blurrily printed samples found in copies of Sejarah (History) textbooks past.

Within, there are records of joy and grief and anger, the entire spectrum of human emotion. There is the social and the political. The economic. Documents both exciting and mundane, all intertwined with any number of constants and changes throughout the age.

Yet at the same time, archives can do so much more than benefit the academy.

It can tell another version of a national story. Take you to a different time and place through someone else’s eyes, someone else’s experiences. Foreground the weird and wondrous that’s been lost to current narratives and highlight the humanity within history, the extent of our detachment, our forgetfulness.

Academics have long used archives as a starting point to germinate some of the most important questions associated with historical inquiry. Why this person? Why this event? Who and what else is missing from this narrative? Why so?

Now that Malaysia is in the midst of re-asking these questions of her own history, it is only apt that these interrogations are not solely limited to a select few.

Let it be commonplace for us, then, to all go into the archives and return from them richer, fuller, having held history in our hands.

JOANNA LEE is in the midst of her PhD, which explores the environmental history of British Malaya. She is currently based in Melbourne, Australia, and has a soft spot for HN Ridley.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.