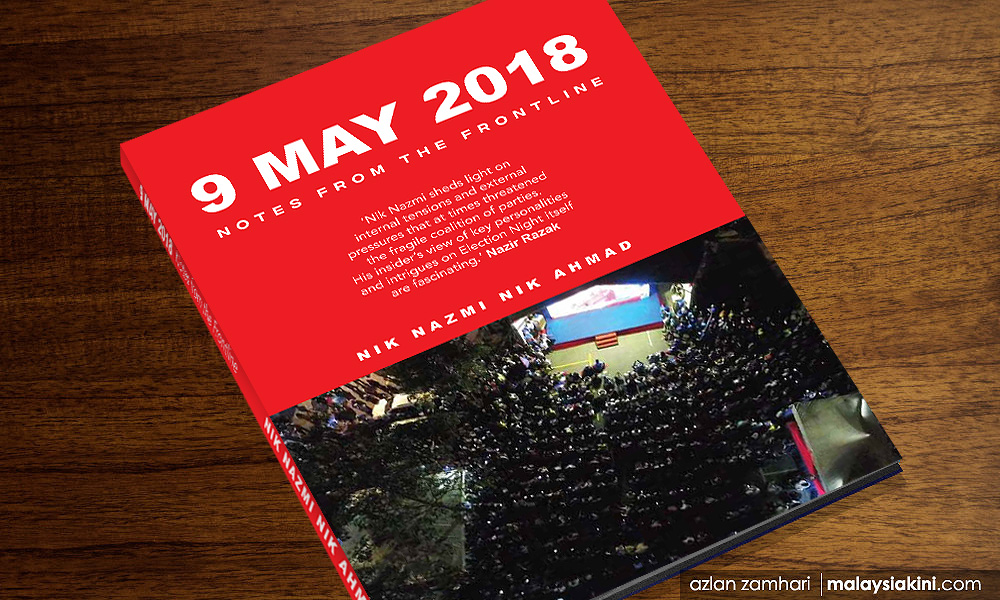

Editor's note: This is the second of a two-part series from Setiawangsa MP Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad's upcoming book, ‘9 May 2018 - Notes from the Frontline.'

BOOK EXCERPT | The Pakatan Harapan presidential council was supposed to meet before the end of 2017 to decide whether to proceed with its first-ever convention.

But that meeting was postponed to Jan 4, 2018 – three days before the convention – stunning the organising committee. On Dec 31, Mohamed Azmin Ali informed that he would “politely decline from speaking at the convention, but will be attending it.”

On Jan 4, the Harapan presidential council gave the go-ahead for the convention to take place. It was only 72 hours before the convention that it was confirmed that it would take place. But negotiations on the prime minister and deputy prime minister candidates, as well as seat allocations, would continue.

Bersatu had initially demanded 80 parliamentary seats. Seat negotiations have always been tricky for PKR, being the most multiracial party not only in the coalition, but the country. We had to fight for Chinese seats with DAP, Malay seats with Bersatu and Amanah, and mixed-constituencies with all the different parties.

As talks dragged on into the last 48 hours before the convention, the issue of the 17 marginal seats that were eyed by PKR became the contention. But PKR handed over eight Malay seats that were previously contested by PAS to Bersatu and Amanah.

PKR was then left with only Titiwangsa and Setiawangsa in Kuala Lumpur. But on the pretext of defending a mixed-seat, Rafizi Ramli and the negotiation team stuck to Setiawangsa. Finally, Bersatu obtained Titiwangsa from Amanah.

We were briefed at a PKR political bureau meeting that a deal was finally reached. The convention was on the verge of not taking place due to the delay in reaching this.

In spite of all the uncertainty, the multi-party convention committee headed by PKR information chief Syed Ibrahim Syed Noh worked hard. Before the confirmation, some members of this group had asked for a definite answer whether the event would take place or not. But when told of the uncertainty behind the scenes, the team understood and continued to focus on making it a success.

The deal was reached the night before the convention for Dr Mahathir Mohamad to be our seventh prime minister candidate and Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail as the deputy prime minister. The new government would expedite the process to release and pardon Anwar Ibrahim. Anwar would be appointed as the eighth prime minister.

Yet someone in the meeting expressed his incredulity at this arrangement – saying that the process for release and pardon will take time. The Malay rulers, he said, would not take well to do something ‘imposed’ by the new government. A few, including me, responded that if Mahathir could accept this arrangement, it would seem funny that Anwar Ibrahim’s own party were cynical about it.

A few days after the announcement, Rafizi mentioned that the seat allocation was clearly to avoid any single party from being dominant in government. While Mahathir had previously pushed for Bersatu to be the dominant partner in Harapan, as it provided certainty and would reassure the Malays, we managed to convince him that the 'big brother’ model of BN was irrelevant.

This would allow all four Harapan parties to push for a more consensual prime ministerial government – as opposed to the strongman style that had been the model since Mahathir’s first stint as prime minister in the 1980s.

In February 2018, it was decided that all Harapan component parties would use one logo for the year’s general election. At the same time, the coalition was working for its registration with the Registrar of Societies.

Two months later, as the registration of the coalition was still beset with hurdles, it was announced that all component parties in Peninsular Malaysia would be using the PKR logo for the coming election. Bersatu was facing challenges with the ROS as well.

For all other parties, this was a big sacrifice, especially DAP, which had contested under the rocket logo since the 1960s. On the other hand, this might calm the Malay voters who were suspicious of DAP and be a more recognisable emblem that the new parties of Bersatu and Amanah could contest under – overcoming the problems faced by Amanah in Sungai Besar and Kuala Kangsar.

At the local level – particularly Selangor – things were still unsettled as Azmin, who had been consistently hostile to the idea of Harapan, made seat negotiations difficult. As the public was entertained with vociferous name-calling, two young PKR leaders dismissed Amanah as having only 1.4 to two percent of public support.

When I raised this with one of the individuals at a PKR Youth political bureau meeting, he said he was merely referring to a survey conducted by Selangor-government thinktank, Institut Darul Ehsan. I retorted that while we can argue until the cows come home on the veracity of the said study, it was unwise to attack our allies like that.

If Fadzil Noor had taken a similar attitude in 1998 and 1999, I argued, Keadilan would not have been given many seats to contest. My point was that we should have appreciated the stand taken by Amanah leaders in supporting our decisions in the past and in the formation of Harapan.

YESTERDAY: Part 1: Witnessing the troubled birth of Pakatan Harapan

NIK NAZMI NIK AHMAD is the MP for Setiawangsa. 9 May 2018 - Notes from the Frontline is published by Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, and will be available at all major bookshops and online by the end of the week. It will be launched by Anwar Ibrahim on Dec 2 at Piazza, The Curve, Petaling Jaya.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.