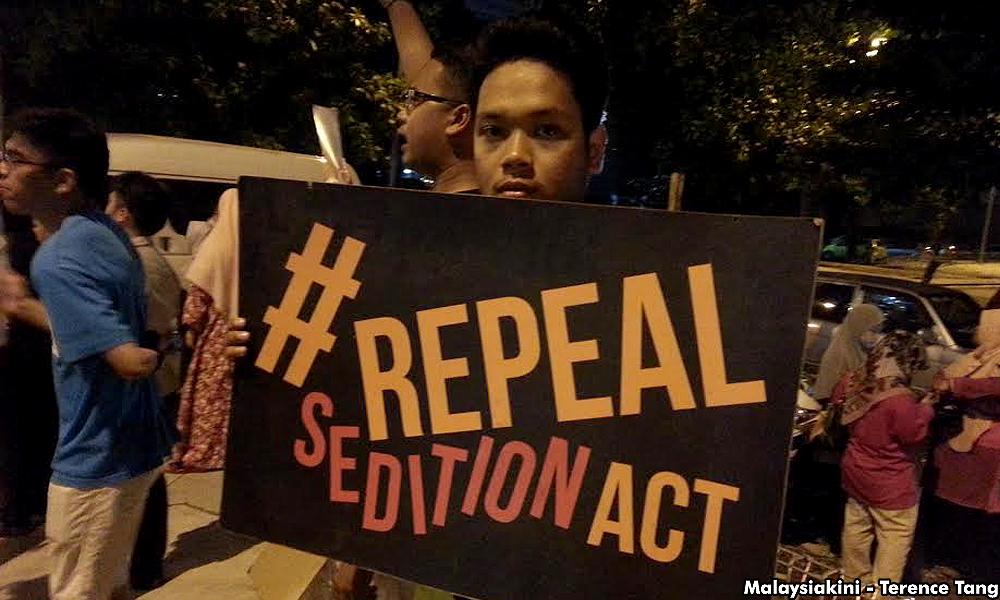

COMMENT | Eight months after the historic results of the 14th general election, the colonial-era Sedition Act is still alive and well. Last week, three people were arrested for insulting the former Yang di-Pertuan Agong and one for alleging that the government protected firefighter Muhammad Adib Mohd Kassim’s killers.

Deputy inspector-general of police Noor Rashid Ibrahim defended the arrests, saying they were to prevent the triggering of situations that could jeopardise the country’s security.

This is hardly the more open climate for discourse and debate Malaysians were expecting following GE14. On top of this, it seems that new laws are being contemplated, including hate speech laws and laws to protect the royalty from insults.

Given the historic abuse of laws that restrict the freedom of speech, and the continued misuse of such laws under the new government, should Malaysia be considering yet another law to regulate speech?

Existing laws

We already have laws in Sections 503 to 505 of our Penal Code that restrict the freedom of speech in order to prevent violence. In summary, these provisions restrict people from making violent threats against others; making insulting statements intended to provoke a breach of the peace; and making statements intending to cause fear that would induce others to commit an offence. It is also illegal to make statements intended to incite one class of persons to commit violence against any other class of persons. This covers inciteful statements that would prompt violent clashes among racial or religious communities.

However, these Penal Code provisions are seldom relied upon, compared to the Sedition Act and the other draconian law, Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA). As with any law, the Penal Code provisions are still open to abuse, and some argue that they still need refinement. Unlike the Sedition Act and the CMA, however, they at least generally require some connection to violence.

The Sedition Act only requires someone to “excite disaffection” against the ruler or the government or to provoke feelings of “ill will or hostility” among the different racial groups for a crime to have been committed. Meanwhile, Section 233 of the CMA criminalises offensive postings intended to annoy others, arguably the broadest restriction on freedom of speech in our country. In neither of these Acts is there any need to prove intention to provoke any violence or the commission of any crime.

Clearly, the Sedition Act and Section 233 of the CMA must go. It is true that freedom of speech is not absolute and can be regulated, but these regulations cannot be so broad as to render the right illusory. Restrictions must be there for a legitimate purpose and must be necessary and proportionate. They must be to protect the human rights of others, and not to protect the vested interests of those in power. These two laws come nowhere near meeting these important criteria when it comes to restricting free speech.

Hate speech law

If the government does repeal the draconian laws stated above, does Malaysia need new laws to restrict hate speech, given the existing Penal Code provisions that criminalise inciteful speech?

It all depends on the purpose for which any new law is enacted. The only purpose hate speech laws should be considered would be to prevent incitement to violence against vulnerable groups, including minorities. They should not be enacted to protect privileged groups from insult and criticism, or worse, to persecute vulnerable minorities. And any such law should operate in conjunction with broader efforts to promote equality and non-discrimination.

Any new law considered must also be narrow in scope, or it risks ending up as a replacement for the Sedition Act. Pakatan Harapan promised to repeal tyrannical laws and draconian provisions, and it would be the worst betrayal if it not only keeps such laws, but also enacts new ones.

Any criminalisation of hate speech should incorporate the six-part threshold test in the Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence. The plan, formulated by international experts, sets out what expressions can be considered criminal offences. This involves examining context, the speaker’s position in society, intent, the content of the speech, the extent of the speech and the likelihood that the speech would succeed in inciting violence.

Not insults, but violence

It is crucial that politicians and the public understand that hate speech legislation is not meant to protect groups from insult and offence. It must be reserved for speech that has a genuine likelihood of provoking violence against groups, and against vulnerable ones in particular.

If that is not made crystal clear in the legislation, then, ironically, the law will likely be used to persecute vulnerable groups to protect the privileged from feeling insulted and offended. Are we not done with such abuses of the law in ‘new Malaysia’?

Getting it right

Apparently not, if we take the past few weeks into account. Who would have imagined that eight months into the new Harapan administration, we would be reading headlines about multiple arrests under the Sedition Act?

Given this climate, can we trust the current government to get any hate speech legislation right? A few things need to happen if the government wants to gain our trust on this issue.

First, it must repeal all oppressive legislation, including the Sedition Act and Section 233 of the CMA, without delay.

Second, the government must demonstrate leadership by meeting discriminatory, inaccurate or offensive speech with reason and education - and not with handcuffs and jail terms.

Third, the government must demonstrate it is able to distinguish between restrictions against the freedom of speech that are overly broad, arbitrary and unconstitutional, and those that are necessary, reasonable and proportionate. And it must articulate this to the public to correct the misconception, caused by decades of the state applying draconian laws, that mere insult and offence can also amount to crimes.

Fourth, any draft law on hate speech should be opened up to the public for consultation and feedback. Yes, there are those who would, unfortunately, oppose laws that call for equality and anti-discrimination. But that would be the best time to conduct public education and have an open discussion on why those principles are essential for new Malaysia to thrive and succeed.

If the Harapan government can do all this, then a hate speech law may be worth considering. If it cannot, then the risk would be that any hate speech law will be a new tool of oppression.

AMBIGA SREENEVASAN is a Commissioner of the International Commission of Jurists and a former Bar Council chairperson, while DING JO-ANN is a writer and lawyer.

The views expressed here are those of the authors/contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.