COMMENT | For the past eighteen months, the Ministry of Education (now the Ministry of Higher Education) had embarked on a progressive project of improving drastically higher education in Malaysia.

Central to this project has been the repeal of the much-criticised Universities and University Colleges Act (UUCA) and its replacement with a new act in line with the broad needs of the much-heralded Industry 4.0.

Town halls and multi-stakeholder discussions – led by independent consultants brought in by the MOE – have been held to look into the mechanisms needed in the act to genuinely propel Malaysian higher education to a much higher level.

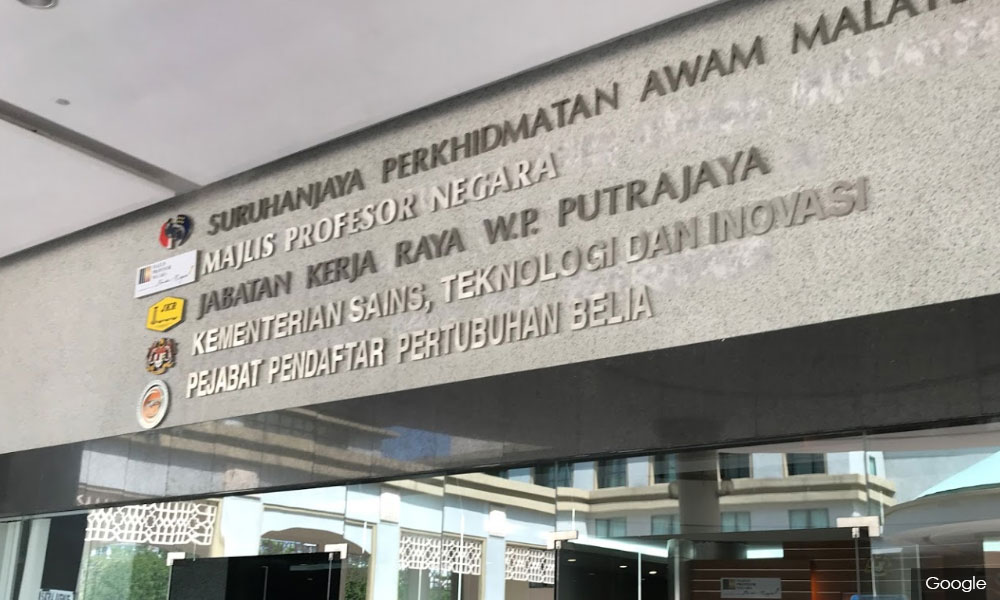

Now we are reliably informed that the evidently-revived Majlis Profesor Negara (MPN) is inviting selected academic groups to prepare a proposal that the MPN plans to submit to the cabinet. It is a proposal for the setting up of a National Higher Education Council (Majlis Pendidikan Tinggi Negara [MPTN]).

We are responding to this because Gerak feels, for a number of reasons which are listed below, that this is an important public issue that requires public discussion.

Gerak, after all, has always insisted on the need for transparency in the way policies on higher education are formulated.

First, we wonder why the MPN has to propose the establishment of such a council when there is already one established by the National Council on Higher Education Act 1996?

Last year, Gerak learned from the ministry that no appointments had been made to the council since about 2012, notwithstanding the fact that the act was still in force.

The ministry added that the reactivation of the council was part of the reform they were about to implement. Details of the reform were published by the ministry for several town hall sessions held last year (2019).

The National Council on Higher Education Act 1996 gives the council extensive powers over the orderly development of higher education in the country. Included in the statutory powers given to the council are powers:

(a) to plan, formulate and determine national policies and strategies for the development of higher education;

(b) to coordinate the development of higher education; and

(c) to promote and facilitate the orderly growth of institutions of higher education.

It is also significant that under the act, the minister of education is required to implement the policies, strategies and guidelines as determined by the council.

It is very clear from even a general reading of the act that the National Council on Higher Education is the sole authority vested with the powers to determine national policies on higher education.

In this role, the council is established as an independent body, independent even from the minister of education. This position is emphasised in other legislation on higher education.

In the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971, section 3, the minister of education is vested with the responsibility for the general direction of higher education and the administration of the act.

But he or she is required to act in accordance with the national policies, strategies and guidelines on higher education formulated or determined by an authority established under any written law for such purposes.

This authority is, of course, the National Council on Higher Education. The same obligation of the minister is repeated in the Education Act 1996 and the Private Higher Educational Institutions Act 1996.

Our second question is, why did MPN wait for almost eight years to take action on the suspension of the national council?

Surely as a respected group of academics, it must have been apparent to them that policies and laws on higher education were being formulated and implemented when the statutory body responsible for the formulation of higher education policies was lying dormant.

Finally, we are also concerned that the MPN, claiming as it did in their communication that it is working with the Higher Education Department (JPT), has failed to make any reference to the six documents that were published by the JPT on proposed reforms to higher education.

These include the proposed reform to give the council greater powers as an independent body, formulating policies on higher education.

We reiterate our intention – public policies in education and other areas of public interest must be made in a transparent manner in the full sunlight of consultation.

No one person or group, however exalted, must have the right to shift the process to the dark areas of self-interest.

The above is issued by the Malaysian Academic Movement (Gerak) executive council.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.