Author Janet Steele, who spent weeks in Malaysiakini office in Bangsar Utama last year, finds out what makes journalists in this online daily tick. This is her second of a five-part series.

Malaysiakini editor-in-chief Steven Gan was born in 1962 in Ketari, a small new village near Bentong in Pahang. The oldest of three children, his father was a bus conductor, and a poor immigrant from the Fujian province of China. His mother was a primary Chinese school teacher from a relatively better-off Cantonese family in town, about 2km from the new village.

Gan (

left

) recalls his father as being "quite dictatorial" when he was young, and at age 14 he ran away from home, ending up living on the streets in Kuala Lumpur. An uncle talked him into going back to school in Kuantan. He later helped Gan to go to Perth to study at a technical college, where he obtained a pre-college degree.

Gan (

left

) recalls his father as being "quite dictatorial" when he was young, and at age 14 he ran away from home, ending up living on the streets in Kuala Lumpur. An uncle talked him into going back to school in Kuantan. He later helped Gan to go to Perth to study at a technical college, where he obtained a pre-college degree.

At the time, his dream was to go to architecture school and learn to build low-cost housing that was "nice but affordable" out of local materials like the bamboo that is abundant in Malaysia. To this day, he still warms to the topic. "With bamboo technology you can build solid housing," he says.

Gan did architecture at University of New South Wales (UNSW). There he joined the Overseas Student Collective, which he credits with having "radicalised" him and made him a writer. In 1983, Gan was elected overseas student director at UNSW.

Later he helped to form a state-wide organisation, followed by a national organisation of overseas students. Others in his circle included Tian Chua (now Batu parliamentarian) and Elizabeth Wong (Selangor executive councillor).

The Overseas Student Collective focused on a number of matters related to "fees, racism, loneliness, and language", but their biggest issue was the introduction of visa fees for overseas students.

After five years in Sydney, Gan went to Melbourne, where he studied philosophy, economics and political science. He continued to be active in the Overseas Student Collective, which is how he came to know Premesh Chandran, who had come to UNSW in 1988 to study physics.

Malaysiakini

chief executive officer Premesh Chandran (

right

) - or Prem, as everyone calls him - was born in Petaling Jaya in 1969. His mother is Bengali, born in Calcutta, and his father was born in Malaysia, although his family is Tamil and comes from Sri Lanka. Chandran's parents met in UK, where they were both studying.

Malaysiakini

chief executive officer Premesh Chandran (

right

) - or Prem, as everyone calls him - was born in Petaling Jaya in 1969. His mother is Bengali, born in Calcutta, and his father was born in Malaysia, although his family is Tamil and comes from Sri Lanka. Chandran's parents met in UK, where they were both studying.

His father went into business, building water treatment plants for the government. After the economic downturn in the mid-1990s, his parents migrated to Australia, and Chandran, then still in school, spent time living with friends and relatives. He describes the experience as having toughened him up, and preparing him to make difficult decisions.

After graduating from university, Chandran came back to Malaysia, where he taught physics at the Universiti Malaya. The job gave him time to continue his activism with Nosca, the Network of Overseas Student Collectives in Australia, and with the human rights organisation Suaram, which he joined in 1992.

After graduating from university, Chandran came back to Malaysia, where he taught physics at the Universiti Malaya. The job gave him time to continue his activism with Nosca, the Network of Overseas Student Collectives in Australia, and with the human rights organisation Suaram, which he joined in 1992.

Chandran and Gan's paths crossed again at The Sun newspaper, where both of them worked in the Special Issues section. Founded in 1994, The Sun was known for "pushing the boundaries of politically acceptable journalism", and giving more space to opposition groups.

The Special Issues section contained longer, thoughtful stories, and was published three times a week. Gan eventually became its editor.

The Special Issues section contained longer, thoughtful stories, and was published three times a week. Gan eventually became its editor.

In addition to Gan and Chandran, two other future editors of Malaysiakini (Nash Rahman and Shufiyan Shukur) also worked there.

A defining moment for both Gan and Chandran occurred when The Sun refused to publish a Special Issues investigation into deadly conditions at one of Malaysia's illegal immigrant detention camps. Some months later, Gan resigned from the paper after editors spiked a column he had written about the arrest of activists at an international conference on East Timor in Kuala Lumpur.

After leaving The Sun , Gan went to Thailand, where he worked for The Nation . Chandran returned to Australia, where he earned an MA in international studies. After finishing his degree, Chandran came home to Malaysia in 1997, and began to work with the Malaysian Trades Union Congress.

Involved with the Internet, various NGOs and political parties during the 1998 reformasi period, Chandran was gripped by the feeling that "we had to do something".

Involved with the Internet, various NGOs and political parties during the 1998 reformasi period, Chandran was gripped by the feeling that "we had to do something".

Some activists were suggesting to start an underground newspaper. However, with the Internet growing slowly, and the government's pledge not to censor the Internet, it made more sense to start something online.

Gan and Chandran managed to raise about RM30,000. Their first plan was to buy a cyber café and run Malaysiakini out of the back. They actually bought a place near Petaling Jaya, but after six months decided to sell the café and keep Malaysiakini .

Malaysiakini's initial funding came from the Bangkok-based Southeast Asia Press Alliance (Seapa). Later they completed a private equity transaction with international venture capital Media Development Loan Fund (MDLF).

MDLF owns 29 percent of the company, and each of the two founders 30 percent. The Malaysiakini staff collectively owns 10 percent. For the first few years, staff members would get year-end bonuses of 15 percent of their salary in shares.

MDLF owns 29 percent of the company, and each of the two founders 30 percent. The Malaysiakini staff collectively owns 10 percent. For the first few years, staff members would get year-end bonuses of 15 percent of their salary in shares.

Even today, Malaysiakini operates on a shoestring. Although starting salaries are comparable with those at the mainstream media, senior editors are paid far less than their counterparts.

There is no overtime pay and, until recently, there was no reimbursement for transport fare. There are only three phone lines on the editorial floor, and callers often can't get through.

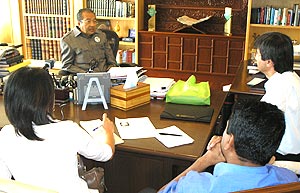

Yet there are compensations as well. People generally join Malaysiakini and stay there because they appreciate what chief editor K Kabilan ( above, in blue shirt ) calls "different thinking, different approaches, and a different atmosphere".

"We should be different," he says. "Our agenda is press freedom."

The development of

Malaysiakini

is intricately connected to that of reformasi, the name for the loose coalition of pro-democracy actors who came together after the sacking of deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim in 1998. "In the aftermath of Anwar's sacking, the Internet as a political medium and as the medium of reformasi became virtually synonymous," says academic Graham Brown.

The development of

Malaysiakini

is intricately connected to that of reformasi, the name for the loose coalition of pro-democracy actors who came together after the sacking of deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim in 1998. "In the aftermath of Anwar's sacking, the Internet as a political medium and as the medium of reformasi became virtually synonymous," says academic Graham Brown.

Chandran's own recollections confirm this notion:

"At that time there were lots of reformasi websites, which were very, very pro-Anwar. We tried to explain that Malaysiakini is going to be a news website, but it's not going to be reformasi, it's going to be independent. And nobody gets it. They say 'if you start a website, you guys are going to be seen like reformasi. And we said no, we are going to have bylines; we are going to write in a professional way."

Thus Malaysiakini's agenda was not "reformasi" in the narrow sense; it was much more than that. As Gan explains, from the beginning their goal was "to create an independent news organisation that would open up the issues of press freedom and human rights, enhance democracy, and show people why these issues were so important."

The press freedom wall

Malaysiakini is located in a four-storey walk-up in the Bangsar Utama neighbourhood of Kuala Lumpur. All that marks the building is a small sign. You have to be buzzed into the building, which Malaysiakini shares with the First Coach Bus service.

At the top of the first flight of stairs is the brick "press freedom wall", which is covered with framed editions of newspapers and magazines that were once banned in Malaysia.

At the top of the first flight of stairs is the brick "press freedom wall", which is covered with framed editions of newspapers and magazines that were once banned in Malaysia.

Behind a door at the first-floor landing are the business office and technical support, both of which are housed in a large room with peach-coloured walls and a royal blue carpet. Chandran's desk sits between two rows of desks, in front of a bookshelf jammed with papers, folders, and reports.

Chandran has a shock of black hair, rimless glasses, and a moustache. He wears a button down shirt and khaki pants, no tie, and is usually focused intently on a laptop computer. A whiteboard behind the programmers lists the ISP addresses, server names, and gateways.

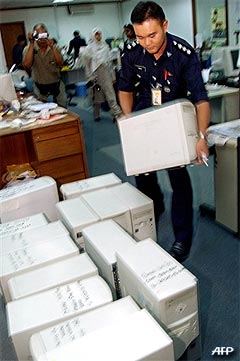

A closed-circuit TV sitting on a table near the wall of windows monitors the front door; it was installed after a police raid in 2003. Three big air-conditioners pump out cold air and several people wear fleece jackets. Walls are mostly bare, except for old pieces of tape, a clock, and a couple of whiteboards. There are parts of old computers lying everywhere.

A closed-circuit TV sitting on a table near the wall of windows monitors the front door; it was installed after a police raid in 2003. Three big air-conditioners pump out cold air and several people wear fleece jackets. Walls are mostly bare, except for old pieces of tape, a clock, and a couple of whiteboards. There are parts of old computers lying everywhere.

The editorial room, one flight up, has a similar layout and the same stained blue carpeting. Gan sits at the head of one of five rows of desks. Desks and chairs crowd the walls, and another closed-circuit TV hangs from the ceiling. Near the door is a glass-topped porch table, with five green and white striped tube chairs.

Newspapers in three languages spill off the table. In a small corner behind the table is the meeting room. There are two whiteboards, one filled with passwords, access codes, and the 2008 election results. The other contains a list of stories ready to be edited or uploaded.

The room is generally quiet, broken occasionally by the sound of talk or laughter. A radio plays softly in the background. For someone who describes himself as an anarchist, Gan runs a tight ship.

Part 1 l How Malaysiakini challenges authoritarianism

Part 2 l 'Our agenda is press freedom'

Part 3 l Holding the powers-that-be accountable

Part 4 l It's called 'watchdog' journalism

Part 5 l Do you have a valid point?

JANET STEELE is an associate professor of Journalism at the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University. Her most recent book 'Wars Within' focuses on Tempo magazine and its relationship to the politics and culture of New Order Indonesia. She is a frequent visitor to Southeast Asia, and writes a weekly newspaper column called 'Email dari Amerika' for Surya daily in Surabaya, East Java.

Malaysiakini

is celebrating its 10th year anniversary on Saturday, Nov 28 with a gala dinner at the Sime Darby Convention Centre in Bukit Kiara. Be there! Seats available from RM100.

Malaysiakini

is celebrating its 10th year anniversary on Saturday, Nov 28 with a gala dinner at the Sime Darby Convention Centre in Bukit Kiara. Be there! Seats available from RM100.

Click here for more information.