COMMENT | We can be easily led to think that preventing multi-cornered contests in the general election is the most important thing for the opposition parties if they want to defeat the BN.

But why did the opposition coalitions do badly in 1990, 1999 and 2013, despite straight fights between main opposition parties against the BN in all parliamentary constituencies in Peninsular Malaysia?

In 1990, while DAP and PAS could not come together under one roof, they were indirectly united by having two separate coalitions with a common leader, Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah’s Umno splinter party, Semangat 46 (S46).

The multi-ethnic Gagasan Rakyat (Gagasan) included DAP, Parti Rakyat Malaysia (PRM), Indian Progressive Front (IPF) and later Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS). On the other hand, Angkatan Perpaduan Ummah (APU) covered PAS and its two splinters, Berjasa and Hamim.

In 1999, DAP and PAS were comfortable enough to come under one coalition, Barisan Alternatif, which had Anwar Ibrahim’s Umno splinter party, Parti Keadilan Nasional (PKN) as the leader and also PRM.

In 2013, Keadilan (PKR), DAP and PAS were members of Pakatan Rakyat, which was five years old and then running four state governments.

So, how did the BN defeat the challenges from the united opposition in straight fights?

The simple answer is communal incoordination - when the opposition coalitions could not mobilise enough Malay-Muslim voters as well as minority voters, especially the Chinese, to vote for them, they failed naturally.

It sounds so matter-of-factly, like 1+1=2. Indeed, it is but often forgotten.

United opposition’s failures

In 1990, Gagasan-APU won about 70 percent of Chinese votes but the Malays held back their support. This was partly attributed to a successful smear campaign by Umno, which accused Razaleigh of selling out Islam and Muslims to the Catholic Kadazans in PBS on the “evidence” that he wore a traditional Kadazan headgear that had a cross-like pattern.

The outcome? Despite Gagasan-APU garnering 43 percent of the popular votes, S46 won only eight seats, PAS, seven, DAP, 20, and PBS, 14, totalling 49 seats or only 27 percent in the 180-seat Dewan Rakyat.

Next, in 1999, the purging and imprisonment of Anwar Ibrahim triggered the Reformasi wave and sent the majority of Malay voters to the Barisan Alternatif. This time, it was the Chinese who held back their support, fearing that a regime change would bring about an ethnic riot.

Indonesia’s anti-Chinese riots in the last days of Suharto (incidentally on May 13, 1998) was fresh in memory. Tacitly, the MCA women’s wing mobilised its grassroots to remind Chinese housewives in the pasar to stock up Maggie Mee and other foods because “election is around the corner”.

The outcome? Barisan Alternatif garnered only 40 percent of votes nationwide, while PAS won handsomely, 27 seats, DAP won only 10 and Keadilan pathetically, only five. Even added with three seats from PBS, the entire opposition won only 23 percent of seats in the 193-seat Parliament.

The 2013 general election saw another round of communal incoordination. According to an estimate by political scientist-cum-parliamentarian Ong Kian Ming, BN’s support in the peninsula surged slightly from 59 percent to 64 percent among the Malays, but dropped drastically from 35 percent to 14 percent among the Chinese and significantly from 48 percent to 38 percent among the Indians.

The 2013 voting pattern was similar to that in 1990, when the Malays held back their support for the opposition. With a much stronger support from the non-Malays, Pakatan Harapan managed to pass the 50 percent threshold in votes nationwide but nevertheless won only 40 percent of the seats.

Malay and Chinese anxieties

What is the lesson from the past three rounds of united opposition’s failure? The key for the opposition to dislodge the BN is a uniform swing across all communities, more than just straight fights.

Do multi-cornered fights matter? Yes, but only in the sense if multi-cornered fights would cause communal incoordination in a swing to the opposition.

The drop in Malays’ support for the opposition coalition in GE13 was largely due to the post-tsunami “Malay anxiety” that Malays might lose out if Umno’s electoral one-party state comes to an end.

For the opposition to win GE14, a strong swing among the Malays – what many hope to be a Malay tsunami – is absolutely necessary. And straight fights would be necessary where the quantum of swing from BN is not enough to ride out vote-splitting due to multi-cornered fights.

But the opposition parties would be foolishly repeating the history in 1999 if they were to take the minority votes for granted. The BN is working hard to win back some Indian votes through the Malaysian Indian Blueprint and other efforts.

The Chinese votes are unlikely to swing back to the BN, because of Umno’s post-GE13 retaliations and reactions, like anti-Chinese violence threatened by groups such as the Red Shirts and its active courting of PAS to enable hudud punishments.

Already frustrated that the BN could not be overthrown despite losing the majority votes, many Chinese feel hopeless and helpless in the onslaught of Umno’s post-GE13 retaliations.

Anxious of their future in a more communal Malaysia, a segment of Chinese voters have grown very distrustful and hostile to opposition parties. The alliance with former PM Dr Mahathir Mohamad and engagement with PAS led them to question if DAP and PKR are the new MCA and Gerakan.

This sentiment may significantly lower the Chinese turnout and put opposition’s marginal constituencies in danger. In fact, BN’s cybertroopers work hard not to swing votes, but to whip up frustration, distrust and anger to bring about lower turnout.

In a sense, the challenge of GE14 for the opposition is to address and overcome “Malay anxiety” and “Chinese anxiety”, which respectively were the outcomes of GE12 and GE13.

Another near miss?

What if the opposition manages to avoid multi-cornered fights largely and ride on a strong Malay tsunami, but suffers significantly low Chinese turnout across the board?

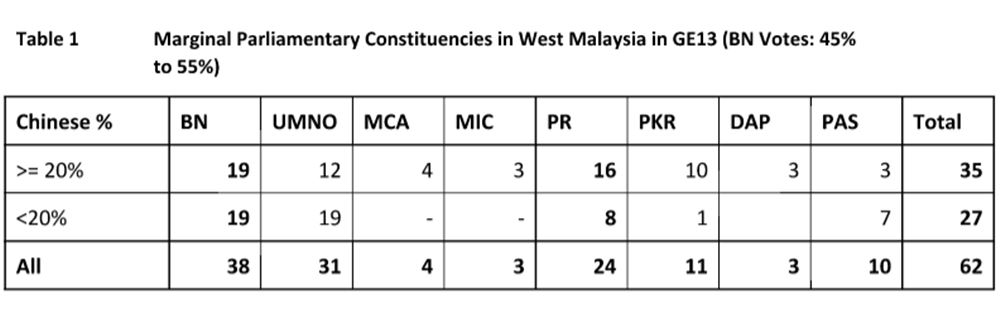

We can narrow our analysis to the 62 marginal parliamentary constituencies in the Peninsular Malaysia, where BN won between 45 percent and 55 percent of the votes in GE13. Here, BN won 38 of the seats while Pakatan Rakyat won the remaining 27. (Table 1)

For ease of analysis, assume, when GE14 is called, no changes in (1) constituency boundary, and (2) ethnic composition notwithstanding new registration and transfer of voters. Only voting patterns change – Malays swing significantly towards the opposition and Chinese turnout decreases significantly.

Regardless of Chinese turnout, a powerful Malay tsunami may mean the opposition winning all the 27 constituencies with lower than 20 percent Chinese voters (25 of them have 80 percent Malay voters), adding 19 seats.

Meanwhile, a large enough drop of Chinese turnout may mean the opposition losing up to 16 marginal seats, where Chinese make up 20 percent or more of the electorate.

If both forces are at work - a Malay tsunami and low Chinese turnout - assuming status quo in other 103 less marginal constituencies, this would mean the opposition can only add three more seats to its 80 seats in the peninsula, not enough even to claim a victory on this side of South China Sea. It will be another near miss, just slightly nearer.

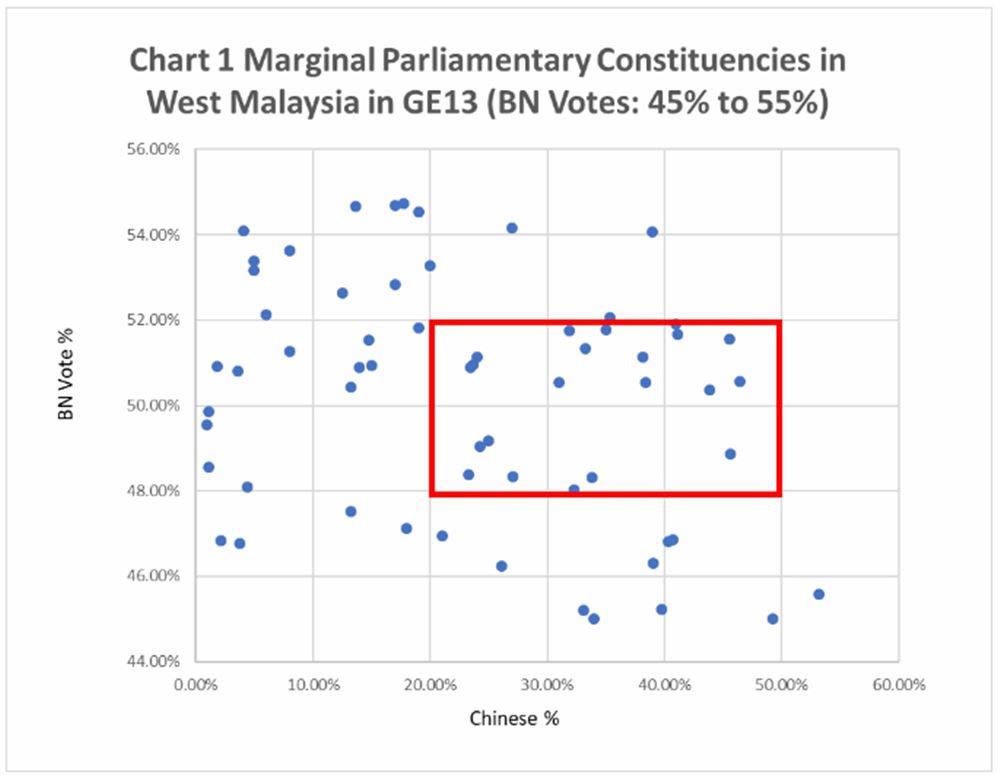

Chart 1 (below) presents the 62 constituencies by BN vote share and Chinese composition, allowing us to adjust the parameters to gauge alternative assessments.

If we reduce the scope to BN vote share between 48 percent and 52 percent, there will be 21 very marginal constituencies (red box in the chart), of which PKR and PAS each won three: Lembah Pantai, Teluk Kemang, Batu Pahat; Bukit Gantang, Temerloh, Sepang. A low turnout among the Chinese would likely mean a handover of these seats to BN.

It is time for the opposition parties and pundits to get the frame right. The opposition’s real challenge is communal incoordination, not multi-cornered fights per se. Multi-cornered fights are obstacles only when they prevent a coordinated communal swing to the opposition.

Part 1: What is more fatal than multi-cornered fights?

Part 2: PAS the kingmaker in GE14?

Part 3: What Malaysia needs is a transition pact

WONG CHIN HUAT is a research fellow with Penang Institute, the state government think-tank on public policy.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.