COMMENT | To overcome communal incoordination, which may be made worse by multi-cornered fights, Pakatan Harapan should present a clear roadmap of what it would change and what it would not.

Let’s be very frank. Corruption scandals, from 1MDB to Felda Global Ventures to Tabung Haji, are not enough to unite Malaysians, let alone throw out of the government.

Malaysia is simply not South Korea or Brazil or Iceland or even Israel.

And while bread-and-butter issues matter, they are not the ultimate determinants of electoral outcomes.

Insofar Umno can make the Malay-Muslims feel that they will lose their dominance after the regime change, Umno will survive no matter how bad the economy is.

The inconvenient truth is that Malaysia is a nation deeply divided on identity line, and as much as we hate to recognise, BN is the minimum common denominator for the society, thus far.

The sophisticated one-party state

More than cultural diversity, division is rooted in economic structure and political system.

We are divided because our life is dictated more by which ethno-religious group we are born in than our individual decisions and efforts.

If the making of our plural society before our independence had made the Malays and the indigenous groups economically backward, Abdul Razak Hussein made the post-1969 state explicitly pro-Malay and in return locked in the Malay-Muslim votes for Umno.

This should not surprise you if you realise that the 1969 election saw a desertion of the ruling coalition by the Malay voters, not by the Chinese voters as the official narratives would like us to believe.

The voters’ communal incoordination in 1990, 1999 and 2013 shows exactly how sophisticated the political system is in self-preservation. Najib survives well because he inherited the electoral one-party state built by his father, which was later transformed into an apparatus for personal rule by Mahathir.

Up until 2008, the regime had two powerful weapons to deter the voters from exodus: for the majority, the threat of losing their dominance, as used against Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah’s Gagasan-APU pact in 1990; for the minorities, the threat of ethnic riot, as used against Anwar Ibrahim’s Barisan Alternatif in 1999.

Double communal anxieties

With the support of one bloc secured, it could then reach out to woo the other bloc. The pendulum-like cyclical politics was accidentally broken by the 2008 tsunami.

When no ethnic riot took place after the near miss on BN, the minority voters gradually realised that the replay of May 13 was a paper tiger. They developed a stronger sense of ownership in national politics and a growing appetite for intercommunal solidarity.

At the Bersih 2.0 rally, thousands of Chinese braved Perkasa’s threats of ethnic riot and hit the streets.

Umno can no longer offer superficial concessions to win back the minority votes but real concessions may alienate the Malay-Muslim bloc. In fact, Mahathir spotted this “Umno’s Chinese dilemma” as early as 2010.

Umno smartly used this growth of minority’s assertiveness to whip up “Malay anxiety” during and after GE13.

After confirming its loss of Chinese votes, Umno post-GE14 moved rightward to secure its Malay-Muslim base in two ways.

First, it used thugs like the red shirts to inflict and threaten violence on Bersih and the opposition. Second, it courted PAS with RUU355, which successfully broke up Pakatan Rakyat and paint it as a Chinese-dominated pact.

The despair that the BN could not be ousted despite losing majority votes, and the opposition’s inability to fight back against Umno’s communal attacks subsequently gave rise to “Chinese anxiety”.

The enthusiasm for change and inter-ethnic solidarity has since subsided amongst the Chinese, with some feeling fatalistic, others feeling betrayed and a minority becoming toxically ethnocentric.

In GE14, Najib will be protected by the growing distrust and antagonism between the majority and minority blocs, thanks to the rise of Malay and Chinese anxieties.

Post-2013 violent incidents from the Low Yat Plaza to Austin Perdana surau affairs suggest conducive atmosphere for communal scuffles to instigate or deter voters.

Strategic ambiguity won’t work

How should Harapan overcome this communal coordination? What is the coalition’s position on thorny issues like New Economic Policy (NEP), religion and language?

The conventional way is called “strategic ambiguity” - avoid the thorny issues and focus on safe issues like corruption and living cost.

This strategy would work only if the opposition controls the media. Why should Umno’s propaganda machines not force Harapan leaders to be clear and possibly contradict one another?

Mahathir’s strategy is minimum disruption. Change Najib first, leave everything later, as if Najib is the root cause and not a symptom.

More than strategic ambiguity, this strategy is to address Malay anxiety. But if post-Najib Malaysia is just going to be pre-Najib Malaysia, how many voters would be excited to queue up to vote?

This will lower the turnout of not only minority voters, but also reform-minded Malay voters too.

Two-step transition pact

But how can Harapan come out with some consensus on issues like NEP and Islamisation in the next few months when the whole nation has failed for half a century?

It can’t and it shouldn’t try. However, pretending the elephant is not in the room is neither a solution. It should take the bull by its horns.

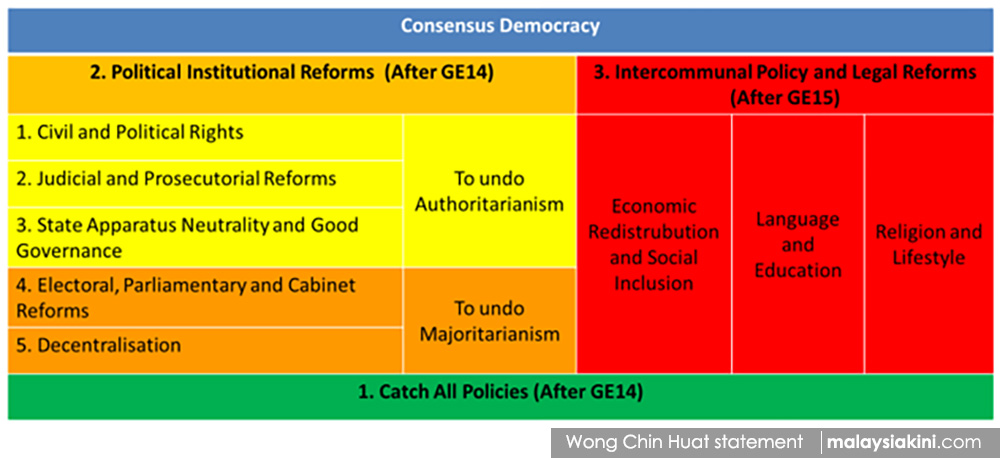

It should offer a two-step transition pact, which separates Umno’s party-state from the intercommunal bargains that it has thrived on. This is to stop Umno from holding the Malay-Muslim voters to ransom. (see chart below)

For the term of the 14th Parliament, it should introduce catch-all policy changes such as abolition of the goods and services tax (GST) and highway toll charges as well as extensive institutional reforms.

Intercommunal bargains on issues like economic redistribution and social inclusion, religion and lifestyle, language and education, should change only after new national consensuses emerge, not just after regime change.

To facilitate this, Harapan should promise broad-based consultative bodies to take two to three years to deliberate and forge consensus on each of the thorny themes.

If the blueprints produced by these bodies are still not accepted by all parties, then they need not be implemented. Rather, let the parties modify blueprints or offer their alternatives in the manifestos for GE15. When the dust settles, the new government can forge new policies based on the electorate’s verdict.

This means GE14 would only be a “transition election” from one-party state, while GE15 would be the “foundation election” for a new deal.

Why consensus democracy?

The new deal should not be just about dismantling authoritarianism. It would require:

- Civil and political liberties - freedom of expression, assembly and association; demolition of censorship and entry barriers in media; no detention without trial.

- Judicial and prosecutorial reforms – reforms in appointment, promotion and retirement of judges; an independent prosecution separate from Attorney General’s Chambers.

- State apparatus neutrality and good governance – impartiality of bureaucracy, police and military; effective watchdog agencies like anti-corruption and ombudsman commissions.

Harapan should also promise to replace majoritarianism with a consensus democracy, which would require:

- Electoral, parliamentary and cabinet reforms – electoral system change; parliamentary reform; term limit and finance portfolio prohibition on prime minister.

- Strengthening federalism and decentralisation – renegotiating federal-state division of power; elected Senate; local government elections.

Muhyiddin has categorically stated Bersatu’s commitment to the prime minister’s term limit and prohibition from holding the finance portfolio. He can do better to propose a private member’s bill to amend the Federal Constitution in the coming parliamentary session to make these promises more credible.

The sceptic may ask, why should Mahathir and Malay nationalists in Bersatu go for a consensus democracy?

Majoritarianism benefits the majority only when they are united. Given the irreversible fragmentation of Malay politics, a consensus democracy serves the best interests of Malay-Muslims, not just the minorities.

As Malaysia celebrates its 54th birthday, let’s think boldly and realistically of changes. That should be the answer to ethnic anxieties, communal incoordination and multicorners. No more business as usual, please.

Part 1: What is more fatal than multi-cornered fights?

Part 2: PAS the kingmaker in GE14?

Part 3: What Malaysia needs is a transition pact

WONG CHIN HUAT is a research fellow with Penang Institute, the state government think-tank on public policy.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.