COMMENT | The 14th general election defeat of BN, which ruled the country since 1957, was testament to the determination of the Malaysian people and civil society who had opposed the coalition’s rule for decades.

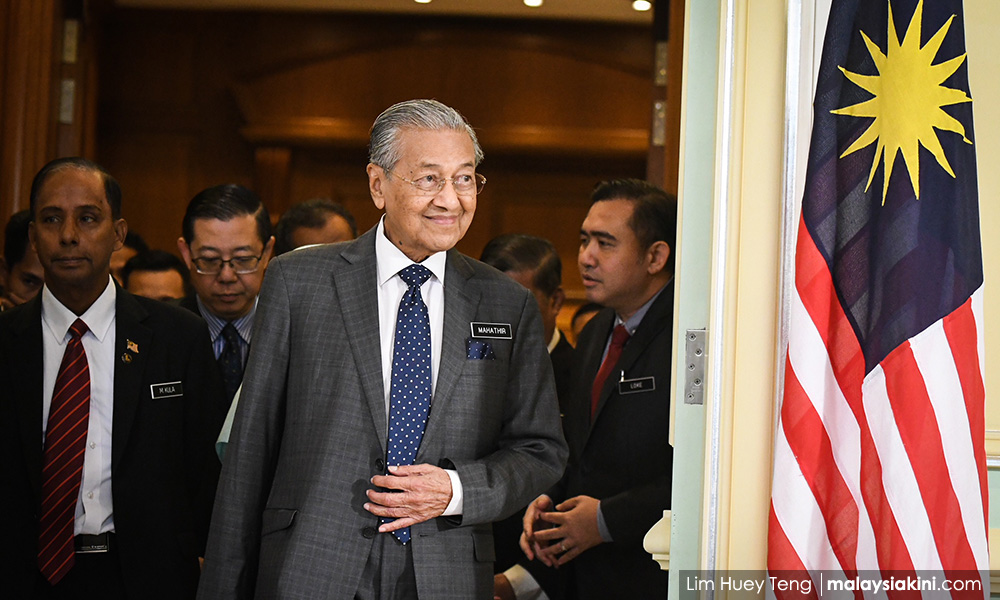

Sixty-one years of BN domination also included 22 years of Dr Mahathir Mohamad at the helm.

The Malaysian people chose to cast their votes for the Pakatan Harapan coalition because it had promised to implement wide-ranging reforms that made them seem radically different from the governance experienced under BN.

In the first 100 days of the new Harapan government, we find that they score about 20 percent in their report card based on their promises alone.

The flip-flopping over the abolition of the National Civics Bureau (BTN) and the National Service (NS) underlines the significance of civil society’s role to oppose such bitterly toxic and noxious institutions.

Nor do Harapan’s promises consider the more comprehensive list of reforms that civil society has long argued is of higher priority. On top of all that, we have witnessed a disturbing trend of autocratic decision-making and policies symptomatic of the old Mahathir era.

Sacrificed at the altar

The convenient opt-out clause for the new government is to pile much of the blame on the previous administration as possible, including the accusation of them of having run up a debt of RM1 trillion, or 80 percent of the GDP, and apparently stealing a further RM19 billion in GST refunds.

That blame game provided the new government with an emotional basis to gain sympathy, such as when they started Tabung Harapan and appealed for donations.

While the way in which these funds will be used remains unclear, it is probably the only fund in the world set up with the apparent aim of trying to plug a country’s debt hole.

It is telling that while a little boy contributed his piggy bank to the fund, the two richest men in the country, who happen to sit in the Council of Eminent Persons have not made a comparable sacrifice.

As for the actual size of the national debt, there is dispute between economists, depending on whether we include government guarantees and lease payments under public-private partnerships.

The size of Malaysia’s government debt in international statistics for 2017 is actually 64 percent of GDP, compared to China’s 65 percent, Singapore’s 110 percent, the United States’ 108 percent and Japan’s 236 percent. Clearly, what is at stake is the country’s economic fundamentals, which the new finance minister assures us are still strong.

It also depends on how the debt is financed – since relying on overseas borrowing can carry higher risks – as well as the country’s prospects for economic growth. Japan has one of the largest public sector debts in the world, but it also has a large pool of domestic savings from which to draw.

Nonetheless, this mythical ‘RM1 trillion debt mountain’ has become an altar on which promises made by Harapan in its manifesto are sacrificed – local government elections, newly-approved Chinese schools, an increase in the minimum wage, abolishing highway tolls and postponing National Higher Education Fund (PTPTN) loans.

This is definitely not acceptable as an excuse for putting off these urgent election promises, since Harapan had assured us they could manage the economy once BN was ousted.

Even the much-trumpeted review of all megaprojects, so as to reprioritise and reduce the debt mountain, is not consistent with the approval of the Penang Transport Master Plan, nor with the recently announced Proton 2.0 project by the prime minister.

Sabah’s infrastructure development minister Peter Anthony also announced that a dam costing RM2 billion would be built at Kampung Bisuang in Papar when Parti Warisan Sabah had promised to scrap the Kaiduan Dam project.

Going private, again

So far, the new Harapan government has not spelled out what they are fundamentally doing differently in terms of economic policy from the old BN regime.

What we have heard so far is the alarming news of the return of old, discredited Mahathirist policies – namely, the privatisation of our national assets in the name of bumiputeraism and the revival of the national car.

The prime minister has said that the sovereign wealth fund, Khazanah Nasional Bhd, will be privatised for the benefit of the bumiputera.

Malaysians need to be reminded that during the financial crisis of 1997, it was Khazanah that had stepped in to take over the assets of failed companies owned by crony capitalists in Renong, MAS and TRI.

Khazanah then revamped these GLCs with professional managers and better rules of governance. It currently owns 51 percent of Plus Expressways, with EPF owning the other 49 percent.

By end 2017, the net worth of companies under Khazanah was RM125.6 billion. Thus, Khazanah successfully achieved its purpose of creating a sovereign wealth fund for the benefit of all Malaysians. It was not set up with the aim of being privatised to benefit bumiputera crony capitalists.

Mahathir’s privatisation drive during his first term was a boon for private crony capital, especially those linked to Umno.

Malaysian taxpayers were the losers since these erstwhile profitable public utilities were sold for a song to private capitalists, and we became captive to Umno-linked monopolies, such as the North-South Highway operator. Furthermore, these failed crony capitalists had to be bailed out with our money during the financial crisis.

During these 100 days, the prime minister had also announced the revival of yet another national car, or Proton 2.0.

After the fiasco of the Proton and the huge cost imposed on Malaysian taxpayers, our public transport system and Malaysian consumers, it is unbelievable that such a failed enterprise could be supported by a Harapan leadership filled with former critics of the first Proton.

Another national car project will surely fail with further losses to the national coffers, and we will have to underwrite the losses. The Harapan government won’t have 1MDB to blame for that anymore.

We should further note that one of Mahathir’s former crony capitalists, Syed Mokhtar al-Bukhary, still owns a majority 50.1 percent in Proton Holdings through DRB-Hicom.

This hare-brained idea to start another national car project reminds me of what somebody said about politicians: “Politicians are people who, when they see light at the end of the tunnel, go out and buy some more tunnels…”

Back to autocracy

It is truly alarming that no cabinet member nor ‘eminent person’ has voiced any objections to Mahathir’s proposed plans to privatise Khazanah and to start another national car.

They will have to bear collective responsibility for the consequences in the event of its failure.

We are witnessing the same ‘silence of the lambs’ culture – for which the DAP used to criticise the BN leaders under Mahathir 1.0 – with the new ministers saying “We’ll leave it to the prime minister” and “I’ll discuss this with the prime minister and let him decide” ad nauseam.

The Harapan manifesto prohibits the prime minister from also taking over the finance portfolio, but Mahathir has in his first 100 days in charge taken over the choicest companies, namely Khazanah, PNB and Petronas under his office.

This is the return to the old Mahathirist autocracy.

Was the cabinet consulted in the decision to start Proton 2.0, privatise Khazanah, Malaysia Inc, or even the revival of the failed F1 circuit?

The appointment of Mahathir and Economic Affairs Minister Mohamed Azmin Ali to the board of Khazanah also goes against the promise of keeping politicians out of publicly-funded investments, since it leads to poor accountability.

Only by insisting on boards being comprised of professionals and rigorous parliamentary checks and balances for such GLCs can we ensure a high level of transparency and accountability.

Mahathir’s response to this criticism was the old feudal justification: “I started Khazanah, so why can’t I be in it?” In other words, he was telling us to stuff our high ideals and democratic principles.

We will have to wait for Lim Guan Eng’s memoirs in the future to see how he responded to Mahathir leaving him out of Khazanah. Did the prime minister even discuss this with him? After all, Khazanah is still under MOF Inc.

If the finance minister is left out of the Khazanah board, how will he be privy to what the Khazanah board is doing? No doubt Mahathir knew that having given the DAP secretary-general the finance portfolio, he could get away with anything.

TOMORROW

The real reforms we expected in the 100 days

KUA KIA SOONG is the adviser of Suaram.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.