MALAYSIANSKINI | Growing up as the son of a teacher, it is no surprise that local publisher Zul Fikri Zamir followed his father's footsteps, becoming a physical education and Malay language teacher at a primary school in Wangsa Maju, Kuala Lumpur.

Recalling his childhood days in Tanjung Malim, Perak, the 32-year-old, better known as ZF Zamir, said his family home overlooked the Sultan Idris Education University (UPSI), an institution known for producing teachers.

Zamir shared his love for books as a boy and the hours he would spend at a secondary school library, which his father was in charge of, pouring through classics such as the Enid Blyton and Nancy Drew series.

However, as a teacher in his adulthood, Zamir soon learnt the difficult realities of being an educator in Malaysia.

"The first six months were very traumatic... I was burnt out in the first year because there really wasn't much teaching," he told Malaysiakini in an interview at The Library Cafe in Kuala Lumpur.

It was not for a lack of skills on Zamir's part but he was assigned to two "end classes", where the primary challenge was to teach students basic literacy skills.

Having visited the United Kingdom in his first year as a teacher, Zamir observed the system there and became convinced that changes were needed in Malaysia's education system, prompting him to co-found the NGO Teach for The Needs.

Teach for The Needs was an after-school initiative meant to help his struggling students to pass the UPSR examination.

It had since grown into a project to help underprivileged students, including refugee children from Syria, with a network of volunteers.

But for Zamir, who cited novelist Faisal Tehrani as a mentor, education wasn't just about passing examinations.

In the first book he authored, "Sekolah Bukan Penjara, Universiti Bukan Kilang (Schools are not prisons, universities are not factories), Zamir highlighted some of the main issues plaguing the education system.

He eventually resigned as a teacher, realising that being an educator doesn't necessarily mean having to be within the system.

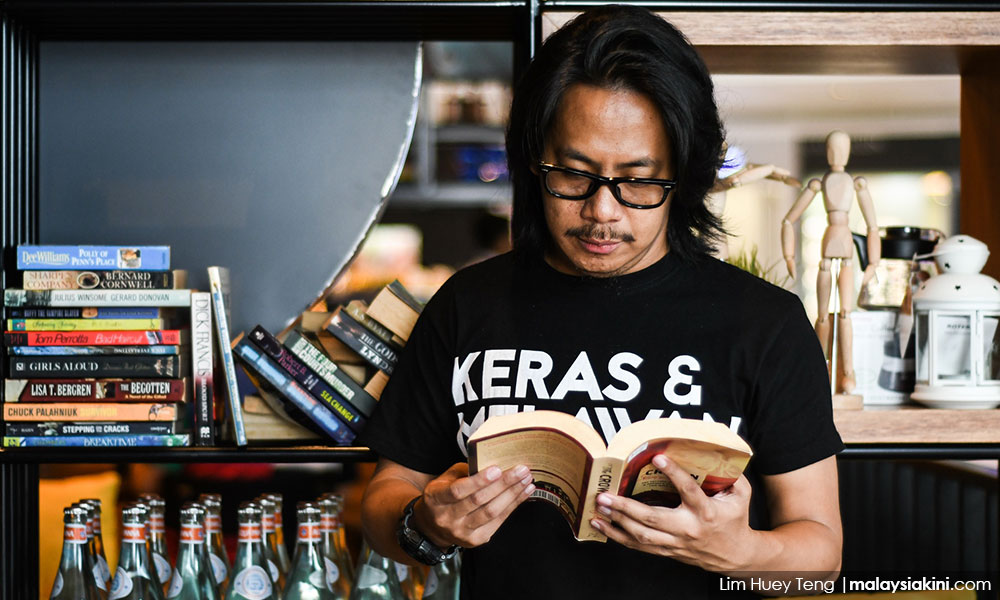

"Liberated" from the system, Zamir began to pursue several projects, including Thukul Cetak, a publishing house that has published several books that are not typically part of the singular narrative in our schools.

Zamir also worked to improve access to these books, with 16 Wakaf Buku (independent libraries) operating nationwide.

These independent libraries provide books that include more than 90 titles published by Thukul Cetak.

Zamir recently resigned as the chief executive officer of the publishing house as he pursued several other projects, including "Bas Tak Sekolah".

In his own words, Zamir talks about education, reading, book bans and his ongoing initiatives.

EDUCATION IS WHERE MY PASSION IS. In the beginning, it was because I had no other options. I failed to enter matriculation college. When all my friends were flying off (overseas) to study engineering, medicine, the teachers' training college was advertising its degree course for the first batch of students. God has had the right plans for me.

THROUGH TEACHING FOR THE NEEDY, WE DISCOVERED THAT MOST CHILDREN ARE NOT LAZY. Their real problem is, among others, they have a lot of other problems at home. Sometimes when we (volunteer teachers) take them out to eat after extra classes, they will ask if they can stay back. When we try to find out, there was one, for example, who revealed that a grandfather at home would 'disturb' the child.

BY READING AND STUDYING, we learn lessons so as not to repeat mistakes. That’s how I started Thukul Cetak. When the Malay version of the Communist Manifesto, which we published, was seized in Jakarta, people asked why we were being provocative. But we see it as education. The (original) book (by Karl Marx) is studied by universities in America. People see it as a propaganda, that we just want to be rebels, but the biggest part is that we want to educate the society.

SOME PEOPLE SAY THUKUL IS RIDING ON THE LEFTIST MOVEMENT. They say we are using the name of (Indonesian poet) Widji Thukul. But Thukul is also a platform for people to learn how to read semi-serious books before they move on to reading the harder books. We have published books on philosophy, translated copies of old transcripts, but people can’t directly jump in to read those books. People will discover the joy of reading when they find the right book. Our tagline is “Keras dan Melawan” and somehow it shaped the crowd.

ONE OF THE REASONS WE SET UP THUKUL ACADEMY WAS TO SUPPORT THE PUBLISHING ECOSYSTEM. We want to receive quality manuscripts, so we opened the academy to teach young writers how to write. We have big ambitions and I shared this with several Indonesian writers during my last trip to Jogjakarta - I want them to come here and hold writing classes.

THE IDEA FOR ‘BAS TAK SEKOLAH’ CAME FROM OUR WAKAF BUKU INDEPENDENT LIBRARY PROJECT. Our aim was to bring the concept of a mobile library to people in the villages. In certain parts of Sabah and Sarawak, our Wakaf Buku libraries are located near schools, almost taking over the responsibility from the government (to maintain libraries). At the very least, we are working towards introducing books to more people.

ONLY 10 OUT OF 50 STUDENTS ARE READING BOOKS OTHER THAN SCHOOLBOOKS. I learnt this when visited a cluster school in Putrajaya a few weeks ago. If children from middle-class families from one of the top schools do not have a reading culture, that is something strange.

They asked, “why do we have to read”? And we must explain to them, the ones who don’t read, they will lack imagination.

READING TRAINS OUR IMAGINATION. Words in books are just fragments. Everyone will have a different interpretation of the words. If the character is an old man, everyone will imagine him in a different way.

THE PEOPLE WHO ARE BANNING BOOKS, THEY DON’T CARE. They don’t read the (banned) books. If someone complains, they (the Home Ministry) will immediately ban the books. That’s it. There is no intellectual discourse there. It’s the same situation when they banned our books.

THE CENTRAL ISSUE AROUND BANNING BOOKS IS POWER RELATIONS. People ban books to remain in power. Faisal (Tehrani)’s books (novels with Shia characters) were banned because the Sunnis felt threatened. They (authorities) feel that to allow Sunnis to think would pose a threat to their hold on power. If we can understand the power relations, then we can understand the issue of book banning.

IT IS UNFORTUNATE THAT WHEN A BOOK IS BANNED, THERE IS NO RESISTANCE. This is a big problem. We writers and publishers face the authorities on our own. We have many influential writers, including some with positions in the government. But they are ignoring this issue. So those in power, they are emboldened to continue banning books.

PEOPLE ASK, WHAT ARE WE FIGHTING AGAINST? We can’t actually answer that. We feel that we need to fight the system. But people can’t relate to that. They don’t see what we are doing right now, (because) we are not holding up placards or hold demonstrations. We are publishing books.

FOR EVERY ONE BOOK WE SELL, THAT IS ONE PERSON ENLIGHTENED. If we publish 1,000 copies of a title and only 100 copies are sold, it would still be done. The books may also be passed on (for others to read). In other words, what we are fighting against is the (entrenched) mindset of the people.

MALAYSIANS KINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.

Previously featured:

Rendering aid to the Rohingya through education

Bringing a ray of hope for refugee children

M’sia's first woman BRT captain drives her way to top

‘Tunku gave us strength to fight for women’s rights’