MALAYSIANSKINI | Lawyer turned composer Saidah Rastam is a good example of the idiom put one's money where one's mouth is.

Like many others in the country, Saidah could not help but to simply exist in what she believed was a state of helplessness and of mere complaining, reading about things "going wrong in the country".

As artistes, Saidah and her friends had wondered what they could do about it as it seemed that they were quite powerless in their given field.

Veteran musician Ahmad Merican's account to her of reversing his car into a pile of documents at Angkasapuri and finding out that they were original music manuscripts was a catalysing event in particular.

"I felt, if that's happening, somebody has got to do something.

"So I told my friend Cheryl Teh (of Khazanah Nasional) that we've got to do something. She said 'why don't you do something', I said, 'okay, I will'."

Her book Rosalie and Other Love Songs was published in September 2014 by Khazanah, a year and a half after she started her research in January the year prior.

"I came to write a history of our music, the heritage and how that heritage has not been carefully kept."

But what did she mean when she said that things were going wrong in the country? Saidah cited two instances which changed the course of the country.

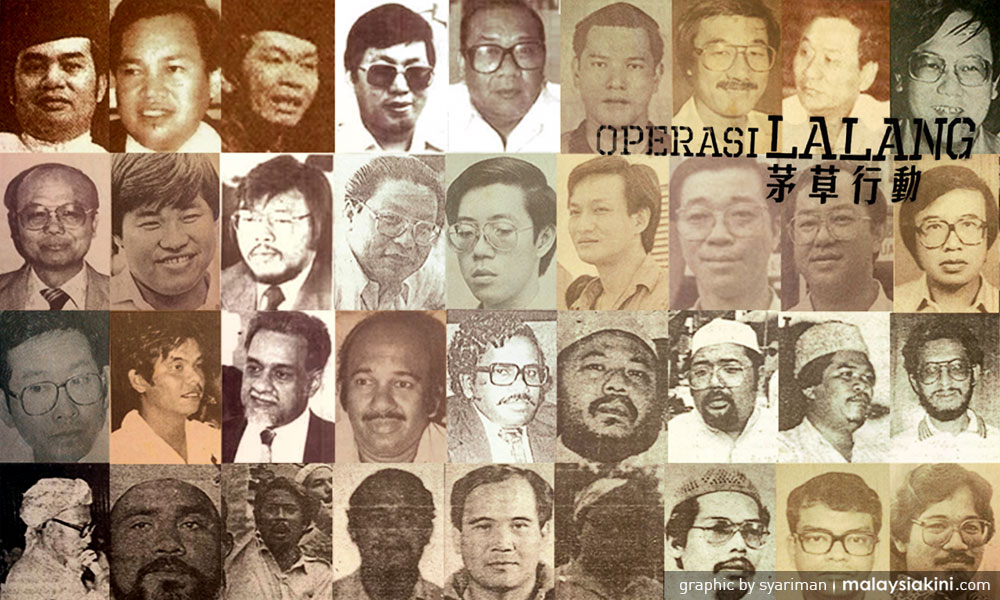

Operasi Lalang broke out as she returned to Malaysia for her pupillage after graduating as a barrister from Gray's Inn.

"Lawyers were going around wearing these black armbands in court.

"I didn't have a clue what was going on. To me, this is law, how come people are bringing politics into it."

The operation simply did not make sense to her. And soon after Operasi Lalang, the judicial crisis had occurred.

"Again I didn't understand what was happening because when you go to study law, you are taught all these notions and ideals (but) the reality is completely different.

"After that, there was the incident where the deputy prime minister (Anwar Ibrahim) was being beaten up and us all sitting in the field with police coming in, it got me thinking, how did it get to this? We're not Cuba, we are a country that's reasonably developed."

No easy black or white answers

Fast forward to today, Saidah said there is both good and bad.

"On the one hand there is what we read in the papers and also platforms like Malaysiakini, The Malaysian Insight, keep us aware of more things than what the mainstream media does.

"On the other hand, if you are only to read that all the time, I think you will get quite a bleak view about the country, which is not the view that I have when going out and working with kids in Akademi Seni Budaya dan Warisan Kebangsaan (Aswara) and going to festivals.

"It's pretty difficult because if you want to say it's bad, how do you say it's bad when all these (good) things are happening. It's not a binary black or white answer."

As a composer who has written music for theatre, film, gamelan, Chinese opera singers, orchestras and electronica to name a few, Saidah recalled how her parents were not open to her studying music initially.

"I wanted to do music, but my parents said, 'don't be crazy, you won't have any income and then your husband will leave you for a 17-year-old and you will be coming back to us, don't do that," chuckled Saidah as she recounted the story.

"My mother said she always wanted her daughters to stand on their own feet."

The eldest of four siblings, Saidah left the legal profession after eight years, at a time in which the "court system was terrible".

"A catalysing event was when my client told me, 'don't worry, the case will be okay'. I said, 'what do you mean?'. So I thought, okay, it's time to get out."

While she does not regret her decision to leave the legal profession, Saidah admitted that she missed it in the first five years.

She recalled how she was treated differently at hotels when she was no longer a lawyer.

"When I sat at the kitchen as a new musician, the waiters told me not to sit there and mess up their cutlery. As a lawyer you never think of that, you're a customer in the hotel."

She also cited a visit to Singapore in her early days as a musician where she had stayed at a three-star hotel and had bugs biting her feet while her husband - Khazanah executive director Charon Wardini Mokhzani - stayed at the five-star Raffles Hotel.

"The next morning, I saw my feet were all red. I called my husband, asked where he was and told him I was coming to stay with him.

"When the taxi dropped me there and I walked in, the carpets were so soft. I was like, 'what have I done, I want to be a lawyer'," laughed Saidah.

While there are both pros and cons to being either a lawyer or a musician, Saidah said she prefers spending her life with "cheerful people".

But before she became a musician, Saidah said she did not realise how people looked down on musicians so much.

"We are the soul. I know this sounds like a cliche; you can have all these buildings (but) if you don't have people singing about emotions and communicating, what is the soul of the country?

"If musicians do that, how come they are not treated with more respect?

"But whether I regret (becoming a musician)? No, I don't. I will never change what I did," she said.

Saidah talks further about herself, music, her research work and the country's state:

I'VE BEEN TOLD HOW I'M A 'FREE HAIR', BUT DO I LOOK LIKE I'M TRYING TO BE A SEDUCTRESS? I don't think so, right. So all these notions which are put on me as a person, I don't think I want to be a seductress, don't tell me I'm being sinful the way I am, I don't feel that. I'm very confused and my friends are on one side or the other. And one question is, what happens to culture, if Mak Yong is not allowed, this and that is not allowed, what's left and what would Aswara teach, then?

When I was teaching in UiTM, that same year, they said that kids could not wear leotards anymore. That means you should just shut down the whole ballet course because it's so ridiculous for everyone to wear big skirts and try to do ballet. Shut this and that down, where will it go? I would like to ask a question in return, what will happen to our culture when more aspects are considered wrong?

THERE'S NO ONE TO BLAME FOR THIS, THAT'S THE WORST THING. Who do you blame? My relationship with my God has always been so important to me but it's nobody's business and I don't want to talk about it to anybody, it's private. People start putting doa (prayers) online, go to funerals and take photos, I'm like, what's going on? Because for me it's supposed to be something personal. Then, by the time you take a step further and you justify self-serving policies by using religion, to me that has been the biggest sin of all. You want to steal, steal. You want to steal and then use religion to back it up, give me a break.

It's very sad, I don't blame anybody, to be honest. It's hard to blame anybody. Every person I knew, my Aswara students have got their own views. If your whole life you've been trained as a dancer and now say you are going to wear the headscarf and therefore you are not going to do dance anymore, I just ask one thing - how are you going to support your children and they said it will be taken care of, but how? If I want to blame anybody, I think the biggest crime has been people who play politics with our education system. Every single education minister, and certainly all of them never sent their children here.

SO MUCH OF MALAY ARTS IS BASED ON WHAT TODAY WOULD BE CONSIDERED NOT ALLOWED BUT IF WE NARROW THINGS DOWN, MALAY ARTS WILL BE EXTINGUISHED. People like Mak Yong performer Zamzuriah Zahari, now she wears a headscarf and she's been told she must not be on stage. I think it's a very complicated time; when anybody says anything, it is seen as disrespectful of the other side. Especially if I say that I feel it's a shame that somebody like Zamzuriah who has so much to impart has done that and gone off stage.

A LOT OF OUR NEGLECT COMES FROM OUR LACK OF AWARENESS OF HOW BEAUTIFUL THIS COUNTRY AND ITS REGION IS. Sometimes we talk a lot about patriotism and nationalism. What does that mean? To me, music can create bonds. If you know the story of the national anthem and you sing it in a loving way like a lullaby rather than like a march, then maybe you can feel that patriotism that we are always being told we should feel, with slogans and campaigns. Why is it that there is so much criticism online about our country, so where is that love?

As for regionalism, just as we sometimes may not be aware of what's going on in our beautiful country, we're just aware of what happens in our little tribe. Similarly, when I was doing this research, one of the things I found out was that our music came from this whole region. It didn't come from Malaysia. Alfonso Soliano, the first conductor of the orchestra of Radio Malaya was from the Philippines. Saiful Bahri who wrote what is until today the most moving patriotic songs Malaysia has ever known was Sumatran. Gus Steyn who created some beautiful orchestral pieces such as Overture of KL was Dutch.

So it suddenly opened up to me this window into a period when things were far more cosmopolitan than they are at the moment. That made me learn more about this region, I had to learn about the Philippines and Indonesia, particularly of the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation. Why were we fighting in the first place? That opened up the history, and the history leads to charming concepts such as Nusantara and Asean.

It's funny that a musician should go out of the comfort zone and need to read about Nusantara, need to read about Asean and open the bigger picture. And it's that bigger picture that I think I'd like to make a point about which is, our culture comes from this region, this bigger archipelago. National walls, nation states are very young in this country, Malaysia was 60 years ago. Likewise Indonesia and Singapore. All of us were created less under a 100 years ago, before those national walls were built. Our people in this region were travelling, there were migrations, fusions. Although people say what hope is there when everybody is saying everything is bad. I say, well actually, looking regionally, there's a lot of hope, there's a lot of possibilities to collaborate and I'm really excited about that.

ROSALIE AND OTHER LOVE SONGS ARE ABOUT OUR MUSICAL HERITAGE, ABOUT ORDINARY PEOPLE MAKING EXTRAORDINARY MUSIC. It's from the turn of the century, from 19th century going on the 20th, when Terang Bulan was floating around the Nusantara - who did it belong to. If a nobility travels for two years, stopping in Penang where the streets have written about it, stopping in Singapore where another papal wrote about it, who does that tune belong to, who can you say it belongs to when it just travels around?

To me, the concept of ownership is quite a western concept. If you look at our great works of Malay literature, nobody writes names on pantuns (poems) or textiles. When P Ramlee created those songs, a lot of the tunes that he used were not his. When I first found that out, I thought this was plagiarism. But actually, if you look further, the whole shared culture of the Malay world is all about not putting your name there and stamping your name there, it's a thing for the community. This gave me another view of heritage. So the book is about our heritage. Who is that 'our', well that's the question.

I FEEL IN MALAYSIA, WE'RE ALWAYS TRYING TO EXAGGERATE OUR ACCOMPLISHMENTS. The problem is, under our noses, there are some amazing accomplishments that we never talk about. So why don't we talk about the real accomplishments? For example in Rosalie and Other Love Songs, things that I found out were, Alias Arshad who came from Negri Sembilan, the son of a paddy planter, goes to Gurney Road where the police depot was, learned music for two years, went to England and graduated from the Royal Military College of Music, top of his class. To me, to learn the notes is already amazing, but graduating top of his class, and coming back and leading the police band, that's amazing.

We had people like Alfonso who came here to this town where we were an illiterate society, musically, in the 1950s. Tunku Abdul Rahman didn't want just a band, he wanted an orchestra. Because if we wanted to be an independent nation, independent nations had to have an orchestra like England. But how are you going to have an orchestra when nobody reads music? In two years, Alfonso and Ahmad Merican created the orchestra. To me, as a musician, that is mind-boggling. Those things are documents, photographs and recordings, to me that's empirical proof of sensational achievements and those are just two.

DISTINGUISHING FACT FROM PERCEPTIONS HAS BEEN THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE IN MY RESEARCH. And wondering if there is such a thing as facts. In scientific experiments, they are quite empirical but in the social sciences, when you interview people and they give one account, then somebody gives you another account but all of them are distinguished people.

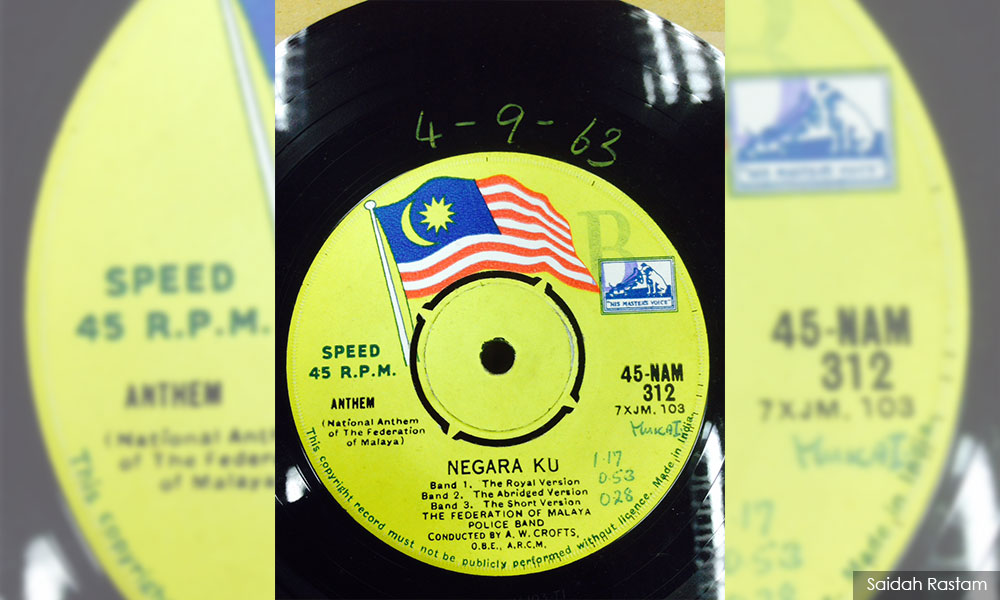

One example is the story of Negaraku. One version is by Mubin Sheppard, one of our most revered historians, another version from Hisham Albakri who was keeper of the rulers' seal, another was the keeper of the Perak royal records. If three people are saying different things about the same events, at least one of them must not be true, but they're all respected historians.

So the challenge was to separate fact from fiction, which then led me to the notion that it's very difficult to say what is fact. What I found was that official books, like coffee table books, contain completely wrong stuff, some of it was a mistake, some of it you begin to wonder if there is an agenda in the writing of history.

When you write a coffee table book, you get to choose. If you put just one version down, then the next student who comes and looks at it, cites your book and you have already stamped it in history. How powerful writers are.

On the other hand, we're still lucky enough because we have veterans, they're not interested in writing, making coffee table books, but when they tell you a story suddenly it all made sense.

I WAS TRAINED AS A LAWYER, IT'S NOT MY JOB TO DECIDE WHO IS TELLING RIGHT OR WRONG. My book doesn't say A or B, I say A says this, B says this, and by the way, C documents suggest that B is right, I just put out all the evidence. I put all the evidence there, the reader gets to decide. That was the hardest part of my research. Because every time you keep thinking, this one is settled, then suddenly it's not right.

In one case, my friend, Retnaguru Sandrakasan - he was with me doing all the recordings - I remember particularly in one interview, we looked at each other as the person was talking, we were saying, 'oh my goodness, so the official record was deliberately wrong'. It's scary. That was the difficult part, but there were exciting parts of research as well.

THE PROJECT I'M CURRENTLY WORKING ON AT THE MOMENT IS TO CLARIFY THE EMPIRICAL HISTORY OF MALACCA, to unearth untold stories. Malacca is very important because our collective consciousness is based on myths that we have been told. I was at the Singapore writer's festival, on the panel this lady was talking about Nusantara and how she's Baba Nyonya and her ancestors came when Cheng Ho brought Hang Li Po over to marry Sultan Mansur Shah.

Those stories, to me, are not entirely based on history. There's a difference between history and myth. The word tawarikh is very interesting, it brings to the fore factualism, empiricism, you have to open the source text. Where does it say that, if it's from Sejarah Melayu, it's seen as a work of literature? I love myths, all of us love myths, so if we want to believe in Hang Tuah then that's fine.

What I'm interested in is that at one point, Malacca was supposed to be this empire, we always read about that. What created that empire? Was it really an empire? If it was, why was it an empire? If an empire is about conquering, then how is this an empire. Because it seems to me that it was a trade emporium. If people did all the trading there, everybody thought that this was an important place, what made it so. Those are the things I want to know.

I JUST FOUND OUT THAT MY ANCESTOR WAS THE FIRST KAPITAN MELAYU AS I WAS LOOKING FOR MALACCA'S HISTORY. In that course, I met Professor Ahmad Adam and he said that my ancestor was the first Kapitan Melayu during the Dutch period and he was a Chinese man. I said, 'a Chinese man who was a Kapitan Melayu?

Going through records in the museum, I found that nine generations ending with my grandmother are sitting there in Malacca. This Chinese guy was in a shipwreck, ended on a beach and a Malay family rescued him. He married the daughter, was good with numbers so when the Dutch came in and wanted to appoint Kapitan Melayu, Cina India, this fellow was well-received by the community, they appointed him Kapitan Melayu. His son and his son all continued to be Kapitan Melayu and of course married Malays, (so the lineage) started to be diluted.

Our history is just all around. My father's other side is Indian, my mother's side, Panglima Kinta who is supposed to have an Orang Asli side, he was a nobility and married a Chinese lady. When I was doing research on Negaraku, it involved the story of how (the then) Perak Sultan went to London and I looked up the national archive for the pictures of the sultan in London, I saw my own great-grandfather sitting in the picture. I was like, 'oh my goodness, maybe there's a reason I was doing this'.

But on my father's side, they were very poor, it was two different sides of society. Generally, I'm very mixed up because economically, my father and mother come from quite different backgrounds while racially, I'm a mix of Malay, Chinese and Indian. It seems a little bit simplistic but I was wondering whether that drives my work on diversity and much more the richness of our pluralism. Maybe yes, maybe not.

THE LACK OF EDUCATION IN MUSIC HELPS A LOT IN SETTING ME APART FROM OTHER MUSICIANS. It did colour what I did because I remember when I was being taught jazz notes by Michael Veerappan, he kept saying 'those are avoid notes, you mustn't play that', but I said 'it sounds very crunchy to me'. So if you don't know the rules, you don't know you're breaking them, that's cool, you just go with what your ear feels and your heart desires.

Later I started learning music, rules, and you realise, this is wrong, this is correct. Now, even later, I come out of that process and I think actually, who says correct or wrong, some teacher somewhere? And they modularise it, this is lesson one, two. What on earth? So many awesome people never followed those rules. My music is ignorant music.

I went to New York University, did two short courses on orchestration and contemporary music. I was taught the fundamentals of jazz by three teachers, I went to Aswara, was taught to play gendang, rebana, patterns of Mak Yong. I did a very interesting project with the Toy Factory in Singapore on Chinese opera. It was a crash course because I was able to interview all these musicians and talk about rules of Chinese opera. So those are things which may be, if I was a real classical musician, I wouldn't go out of because I'm just really defining the 10,000 hours there. Here you just mix it up and something good happens.

M! THE OPERA WAS MY MOST MEMORABLE WORK BECAUSE I THOUGHT THAT I HAD DONE THE BEST MUSIC OF MY LIFE YET THE AUDIENCE'S RESPONSE WAS LUKEWARM. For eight years I didn't compose again. I started thinking "what is it about this country". Thankfully, I came out of that (situation) because I realised that other people went through so much and they continued making music. M! the Opera was a project to combine western operatic singing with Malay styles of singing. People in there included Zamzuriah and actor Khir Rahman. Working with those people was amazing.

Looking back, I think that music is bloody brilliant. Sometimes you age ten years, one day you put on the CD, you're scared, you make sure nobody's in the room, you play it. And I was just crying, I thought this is so beautiful. It's very easy to create commercial music. It's not so easy to create art and that was what I was trying to do. I was just trying to create non-commercial music.

I HAVE A WEAKNESS FOR HUMAN VOICES, I know some people prefer instrumental bands. For me, when people sing, there's so much connection. It's not just me, you have all these superstars singing, with the whole place going bananas be it Akademi Fantasia or Britain's Got Talent. But I love that, no amount of digital wizardry can do that, that's why sometimes you can have a whole orchestra of 80 then one singer who delivers it.

I THINK TODAY MORE AND MORE YOUNG PEOPLE ARE SAVVY, THEY DON'T DEPEND ON AGENTS OR RECORDING COMPANIES, they've taken ownership of the distribution process and I think things will change, definitely. If you look at (songwriter) Rendra Zawawi, for example, so many of our guys today. People always mention Yuna but Yuna, to me, is an outlier. She was phenomenal, but she doesn't inform the conversation.

To me it's more the triumph of people; music groups who are now doing it for themselves, applying to competitions, getting stuff on the internet, getting to be part of the global conversation themselves. That, to me, is a triumph. Those days, Malaysian musicians in my era, just played music and then wait and hope the recording company will distribute. Nowadays, musicians are in charge, so yes, I'm convinced that things will change. Also, I believe it has been a democratisation of the industries. People know that the people working in T-shirts, slippers, can be an internet millionaire and people have seen too many titled people arrested.

WHEN WE TALK ABOUT THE FUTURE OF MUSIC, I WOULD REALLY LIKE FOR US TO REVISIT WHAT WAS IT THAT MADE OUR MUSIC SO UNIQUE, that made scholars from overseas come to study it. In the 1960s our country was on a quest for modernity. Actually, some of the most beautiful music in the world already existed with us. And our oral music, which has melismas - our guys have that when they sing keroncong, those things already exist in our music. However, when we formed our music policies, Malaysia was looking at pre-modern so we used jazz from the Berklee College of Music.

When I was talking to Indonesians, they said the same about their gamelan. If you take a gamelan set, detune it a little bit, when one gamelan plays with another one, all those sound waves in the middle are mixing in a funny way. If you do a regularly shaped tune like an electronic instrument, you can't get that. It's all these detunes, some people say it's out of tune but I don't think so. The Japanese have got a word for it, wabi-sabi - it is the notion of ugliness actually being a beautiful thing, the imperfection in beauty. If you look at Zamzuriah and the other Mak Yong ladies, they sing and it cuts across a thing; that is beauty.

MALAYSIANS KINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.

Previously featured:

Living life in the face of muscular atrophy

Lighting the way for neglected girls

The rebel educator who seeks to enlighten people

Rendering aid to the Rohingya through education

Bringing a ray of hope for refugee children